The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (22 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

‘People - whether they know it or not - like their blues singers miserable. Then they like them to die afterwards.’

Janis Joplin

OCTOBER

Sunday 4

Janis Joplin

(Port Arthur, Texas, 19 January 1943)

Big Brother & The Holding Company

Whether it was in her music, her beliefs or indeed in her sexual predilections, Janis Joplin always had another new barrier to break down. Despite its supposed manifesto of freedom for all, the hippy culture of the late sixties could be sexist and challenging; Joplin was one female figure who cut through this – just as her pure, strident tones had cut through the suffocating industrial air of her oil-refining home town all those years before.

‘Don’t compromise yourself – you are all you’ve got.’ An unreconstructed rebel, Janis Joplin destroyed many of her own personal demons while railing against the wrongs she saw elsewhere. She hated segregation: one of her last actions was to buy a headstone to commemorate her heroine Bessie Smith – the blues singer refused access to a whites-only hospital when she was dying in 1937. The powerful tones of Smith were what initially drew Joplin to the blues, coming as she did from a background of, on the one hand, the country music played by her siblings, and on the other, the opera preferred by her parents. Joplin heard in Smith’s a voice that could precipitate change (in whatever form), and set about exorcizing her ‘sweet little chorister’ image.

Janis Joplin’s first battle, though, was with her own identity: she was an ‘unlucky’ teenager in that she was smitten with acne and developed what she felt was an unflattering figure. An outcast, she tended to fraternize with an unseemly element with which her burgeoning tearaway image made her popular. Joplin frequently flitted across the Texas border to Louisiana’s forbidden world of cheap roadhouses and live music (two of the four pastimes that would always remain her favourites). University days brought a second battle: although she joined her first band, she found herself voted ‘Ugliest Man on Campus’ by some basic types at Austin’s University of Texas. The end result of such humiliating, low-rent sexism was that Joplin dropped out to work as a singer, her first step towards becoming the biggest female star in US rock – and, for many, the greatest white blues songstress of all time. Yet it very nearly didn’t happen. Having lost an alarming amount of weight (mainly due to her use of amphetamines), Joplin returned to her parents’ home in 1964, to try to neutralize her increasingly ripped-away lifestyle. Hard to imagine, but she tidied herself up, bought some dresses and even considered marriage and secretarial work. Two years later, though, Joplin was back on the scene: musician, poet and friend Chet Helms caught one of her ragged live performances and took the singer to San Francisco to meet Big Brother & The Holding Company, a so-so Bay Area band needing a vocalist (Joplin had already turned down The Thirteenth Floor Elevators). Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrews, who was to accompany Joplin through the remaining phases of her career, stated: ‘It took her a year to learn to sing with us, and a year to dress the part. She was always gonna be one of the boys.’ In spite of a largely forgettable first album, Big Brother featuring Janis Joplin knew how to party on stage, and – like Jimi Hendrix – were an absolute smash at Monterey in June 1967. One who thought so was Bob Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, who managed them as a result, securing a deal with Columbia. A second album, under the abbreviated title of

Cheap Thrills

(originally

Dope, Sex and

. .

.

), crashed into the US charts, astonishingly topping them for two months – while spawning the huge hit single ‘Piece of My Heart’ (originally recorded by another of Joplin’s inspirations, Erma Franklin). By now, however, Joplin had moved on. Encouraged to go solo by those who felt she was carrying Big Brother, she made a couple of attempts at fashioning her own backing band, first with the sprawling Kozmic Blues Band and then, with greater success, the somewhat stripped-down but musically much-improved Full Tilt Boogie Band: John Till (guitars), Richard Bell (piano) ( June 2007

June 2007

), Brad Campbell (aka Keith Cherry, bass), Ken Pearson (organ) and Clark Pierson (drums).

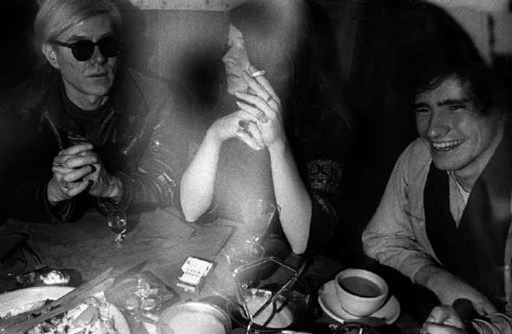

Janis Joplin: Just caffeine and nicotine, this time, with since-departed friends Andy Warhol and Tim Buckley

( June 1975)

June 1975)

‘On stage, I make love to 25,000 people. Then I go home alone.’ As she became a major star in America, Joplin’s performances became ever more explosive, more rampant, more sexually charged and more confrontational. Her renewed lifestyle of full-on sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll similarly showed little sign of letting up. Joplin had affairs and relationships with both men and women (not least Peggy Caserta, who documented most of their activities in her ‘fuck and tell’ journal,

Going down with Janis).

She drank to excess – usually tequila or Southern Comfort – and was described by stalwart Andrews as ‘more aggressive, loud and belligerent than ever before’ when inebriated. Given her caustic wit, this made for some interesting moments, one such being a stand-up fight with a female Hell’s Angel (which she won, obviously), another her clouting of Jim Morrison with an empty bottle of Jim Beam and a third her appearance on NBC’s

Dick CavettShow,

where she warned former schoolmates of her imminent return for a tenth-year reunion: ‘They laughed me out of class, out of town and out of state – so I’m goin’ back!’ In the event, it was to be her last visit to her family home.

It was Janis Joplin’s voracious heroin intake that caused most disquiet among her colleagues. She was shooting up junk and had already overdosed non-fatally five times, but she found kicking the habit too much like painfully hard work and by mid September she was once again on the needle. On the evening of 3 October 1970, Janis Joplin returned from an arduous day at the LA studio where she was recording vocals with Doors producer Paul Rothchild for her latest, as yet untitled album. A track, ‘Buried Alive in the Blues’, was all set for her magic touch the following day. She needed to make up some ground following the less-than-ecstatically received

I Got Dem Ol’ Ko%mic Blues Again, Mama,

her last long-player. After leaving the studio, Joplin chugged down several Screwdrivers (by way of a change) with Pearson at Barney’s Beanery on Santa Monica Boulevard before returning to Room 105 at the Landmark Hotel, Franklin Avenue, a well-known place for rock stars to hook up with their dealers. On this occasion, Joplin’s supplier, George (her preferred dealer, for fear of receiving cut drugs), was, unbeknown to her, out of town and the heroin she picked up had not been pharmaceutically checked – at least, not by anyone she knew or trusted. Joplin bought a vending pack of cigarettes, took her change and returned to her room: she chose to skin-pop the drug, a method of injection that gives a delayed hit. Joplin was found, sixteen hours later, by her road manager, John Cooke: she was clearly dead, clad only in a blouse and underwear, with the change from the cigarette machine still clasped in her hand. Although Joplin appeared to have collapsed and hit her head on a nightstand, the likelihood is that the heroin (according to doctors, close to 40 per cent pure, as opposed to the street ‘norm’ of 1–2 per cent) killed her outright. Also found in the room was Joplin’s ‘hype kit’ – gauze, cotton wool, a towel and syringe. Finally, a red balloon was ‘returned’ to Room 105: inevitably, it contained heroin.

The next evening, the numbed survivors of The Full Tilt Boogie Band retired to Clark Pierson’s house to remember Janis Joplin and smoke a few joints in her name. With the extracted cut ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ making Janis Joplin the latest dead idol to have a number-one single, their album would be released, incomplete, as

Pearl,

Joplin’s lifelong nickname. And it, too, would hold the US top slot – for nine weeks – with the track ‘Buried Alive in the Blues’ included as an instrumental.

Surviving Jimi Hendrix by just two weeks ( September 1970),

September 1970),

Joplin had mused whether she might receive similar press coverage if she were to die. That said, there is no evidence to suggest her death was anything other than misadventure, thus suicide speculation and conspiracies should be ruled out.

The hotel, now known as the Highland Gardens, maintains that the ghost of Janis Joplin still inhabits Room 105.

See also

James Gurley ( December 2009)

December 2009)