The End of Diabetes (7 page)

Read The End of Diabetes Online

Authors: Joel Fuhrman

Â

Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load of Common Carbohydrate-Containing Foods

3

Carrots are a good example of the lack of precision inherent in using only the glycemic index. They are high in fiber and nutrient rich, but their GI is 35. Carrots are relatively low in calories, and when they are eaten raw their glycemic effect is lessened further, as the body does not absorb all of the calories in raw foods. The GL is the accurate measurement here, not the GI. Carrots are not a negative food, even for the diabetic, as the GL is only 3. This is why raw carrots are a favorable weight lossâpromoting food. Instead of focusing narrowly on the concept of GI, we have to consider the other values of the food as well as the healthful qualities and GL of the entire meal when put together. By the way, weight loss and micronutrient adequacy are more important than minor and temporary fluctuations in blood sugar, because they lead to long-term wellness and resolution of the diabetic condition.

Studies evaluating the negative effects of a higher glycemic diet revealed that foods composed of low-nutrient, low-fiber, processed grains and sweets have deficiencies, and they harm far beyond their glycemic response. Processed foods are also low in fiber, phytonutrients, and antioxidants and are rich in toxic acrylamides. In addition to having a high GL, they are disease-promoting foods. When a diet is rich in nutrients, the disease-protective qualities of these foods and their weight-loss benefits overwhelm any insignificant drawback from their moderate GL.

U

NDERSTANDING THE

G

LYCEMIC

I

NDEX

Food | Glycemic Index | Glycemic Load |

White Potato (1 medium baked) | 90 | 29 |

White Rice (1 cup cooked) | 68 | 29 |

Brown Rice (1 cup cooked) | 58 | 24 |

White Pasta (1 cup cooked) | 53 | 21 |

Chocolate Cake (1â10 box cake mix + 2T frosting) | 38 | 20 |

Raisins (1â4 cup) | 64 | 19 |

Corn (1 cup cooked) | 52 | 18 |

Sweet Potato (1 medium baked) | 69 | 14 |

Black Rice (1 cup cooked) | 65 | 14 |

Grapes (1 cup) | 59 | 14 |

Rolled Oats (1 cup cooked) | 55 | 13 |

Whole Wheat (1 cup cooked) | 30 | 11 |

Mango (1 cup) | 51 | 11 |

Lentils (1 cup cooked) | 40 | 9 |

Apple (1 medium) | 39 | 9 |

Kiwi (2 medium) | 58 | 8 |

Green Peas (1 cup cooked) | 53 | 8 |

Butternut Squash (1 cup cooked) | 51 | 8 |

Kidney Beans (1 cup cooked) | 22 | 7 |

Blueberries (1 cup) | 53 | 7 |

Black Beans (1 cup cooked) | 20 | 6 |

Watermelon (1 cup) | 76 | 6 |

Orange (1 medium) | 37 | 4 |

Carrots (1 cup cooked) | 39 | 3 |

Carrots (1 cup raw) | 35 | 2 |

Cashews (1 ounce) | 25 | 2 |

Strawberries (1 cup) | 10 | 1 |

Cauliflower | negligible | negligible |

Eggplant | negligible | negligible |

Tomatoes | negligible | negligible |

Mushrooms | negligible | negligible |

Onions | negligible | negligible |

Recently a systematic review was performed of published human intervention studies comparing high- and low-GI foods or diets and their effects on appetite, food intake, energy expenditure, and body weight. In a total of thirty-one short-term studies, the conclusion was that there is no evidence that low-GI foods are superior to high-GI foods in regard to long-term body weight control.

4

More recent research compared the exact same caloric diets, one with a lower and one with a higher GL, and demonstrated that lowering the GL and GI of weight-reduction diets does not provide any added benefit to calorie restriction in promoting weight loss in obese subjects.

5

So the GI and GL are important, but they cannot be the primary focus of a healthy diet. They are just one of many aspects to be considered when understanding what makes this proposed diet style ideal. This will come into play in the design of the optimal diet and best carbohydrate choices in chapter 6.

The important point to remember is that a diet with a high micronutrient density already has a favorable GL. It is also low in saturated fat, high in fiber, rich in phytochemicals, and naturally alkaline. In other words, instead of focusing on one positive aspect alone, consider all the positive features of what makes a diet style disease protective. Fad diets too often rely on one aspect of food and digestion regardless of the potential positive and negative factors that exist simultaneously. So the GL plays a role in designing the optimal reversal diet for a diabetic, but let's not allow the GI or the GL be the sole determinant of our diet.

Also keep in mind that nutrient-density scoring is not the only factor that determines good health. For example, if we ate only foods with a high nutrient-density score, our diets would be too low in fat. So we have to pick some foods with lower nutrient-density scores (but preferably the ones with the healthier, higher nutrient-containing fats such as seeds and nuts) to include in our high-nutrient diet. Additionally, if thin or highly physically active people ate only the highest-nutrient foods, they would become so full from all of the fiber and nutrients that they would be unable to meet their caloric needs and would eventually become too thin. This, of course, gives you a hint at the secret to establishing a permanent low body-fat percentage if you have a metabolic hindrance to weight loss. But, shhh, don't tell anybody about this.

Optimal health cannot be expected without attention to the consumption of high-micronutrient foods. For example, a vegan diet, centered on high-starch foods such as white rice, white potatoes, refined cereal grains, and bread products, does not contain sufficient micronutrient richness for maximizing longevity. In some susceptible individuals, the lack of attention to micronutrient density may even be disease causing.

Hundreds of individuals have lost over a hundred pounds, some even more than two hundred pounds, and several more than three hundred pounds by following this nutritarian diet. Countless others have just lost the amount of weight they needed to earn back their health. But it is not just about weight loss. Utilizing large volumes of nutrient-rich vegetation in the diet has been demonstrated to lower cholesterol more effectively than cholesterol-lowering drugs.

6

My patients routinely and predictably see their blood pressure return to normal and their atherosclerotic heart disease or peripheral vascular disease melt away as well.

Another revolutionary finding besides the importance of consuming a sufficient quantity and variety of nutrients is that high-nutrient eating suppresses your appetite. You naturally desire fewer calories. So although this book is about eating less, you don't realize you are eating fewer calories and you don't desire more calories. The nutritarian diet style blunts your desire to overeat. In the following pages, we will discuss this added benefit and the ins and outs of hunger and cravings.

Reversing Diabetes Is All About Understanding Hunger

Dr. Glen Paulson was a forty-year-old chiropractor and father of four. He suffered from uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, diabetic neuropathy, kidney stones, high cholesterol, and obstructive sleep apnea. He weighed 330 pounds, his fasting blood glucose level was 240, his HbA1C level was 10.4, and his blood pressure was 145/90 on metformin 1,000 milligrams twice daily and Glyberide 5 milligrams twice daily. His physician wanted him to go on insulin because his blood sugar could not be controlled on oral medication and also wanted him to add more medication to further lower his high triglycerides and high blood pressure.

Dr. Paulson recalls, “My kidneys were shutting down, I had stones, and I was constantly in pain. My doctor told me if I didn't change my diet, I would need dialysis in a few years. When I turned down the medication request the nurse gave me over the phone, the doctor called me back and explained the risks to my health and how serious a matter it was. I got off the phone, and I just cried.

“I read

Eat to Live

and decided to change. I had been ignorant and reckless with my health.” Eight weeks later, when Dr. Paulson went back for a checkup, his physician hugged him and said he never saw anyone reverse so many health problems just from diet and exercise.

After six months of following my advice, Dr. Paulson lost eighty pounds, his fasting blood glucose level lowered to 90, his HbA1C level went to 6.5, and his blood pressure reduced to 120/70. His only medication at the six-month marker was metformin 1,000 milligrams twice daily.

*

Dr. Paulson's wife, Jillian, also lost thirty pounds. She told us Glen “is doing so much better. He has been a good example for his patients, and they are changing their diets as well. When they see what happened to Glen, they all want to lose weight and get off their medications too because of his good example. This is the best lifestyle change we have ever made, and we 100 percent promote this plan. We now teach a health class on this once a month, and it has been phenomenal. Thanks for everything.”

A

high-micronutrient diet does not just improve health for your body, but it also decreases food cravings and sensations leading to overeating behavior. Individuals adopting a diet style rich in micronutrients report a change in the perception of hunger signals. The sensations commonly considered hunger, and even reported in medical textbooks as such, appear to dissipate for the majority of people, and a new sensation that I label true or throat hunger arises instead.

A diet too low in micronutrients leads to heightened oxidative stress. Oxidative stress means inflammation in the cells due to excessive free radical activity. It is accompanied by a buildup of toxic metabolites that can create physical symptoms of withdrawal when digestion ceases in between meals. Besides the toxins we consume from food, cells produce their own metabolic wastes that need to be removed from cells and tissues.

When our diets are low in phytochemicals and other micronutrients, we build up intracellular waste products. It is well accepted in scientific literature that toxins such as free radicals, AGEs, lipofusion, and lipid A2E build up in tissues when people's diets are low in micronutrients and phytochemicals, and that these substances contribute to disease.

1

It has already been noted that overweight individuals build up more inflammatory markers and oxidative stress when fed a low-nutrient meal compared to normal-weight individuals.

2

Because of this, people prone to obesity experience more withdrawal symptoms that direct them to the overconsumption of calories. These are the sources of the toxic hunger cravings that often lead to binging and other gut-busting behavior. It is a vicious cycle promoting the problem and preventing its resolution. Those with healthier diets do not build up such high levels of inflammatory markers and as a result do not experience intense withdrawal hunger symptoms.

3

Phytonutrients are required for the body to properly detoxify metabolic waste productsâthey enable cellular detoxification. When we don't eat sufficient phytochemical-rich-vegetation and instead consume low-nutrient food and excess animal proteins (creating excess nitrogenous wastes) we often exacerbate the buildup of metabolic waste products in our bodies.

4

These wastes are just like drug toxins.

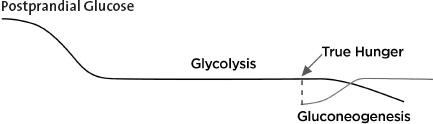

The withdrawal symptoms, conventionally called hunger, develop from inadequate or poor nutrition. I call these withdrawal symptoms toxic hunger. It is important for us to understand and differentiate toxic hunger from true hunger. Toxic hunger appears at the lower plateau of the blood sugar curve, drives overeating behavior, and strongly increases the desire to consume more calories than the body requires, leading to weight gain and diabetes. True hunger, however, appears when the body has used up most of the calories from the previous meal as well as the stored glucose (stored as glycogen) and is ready to be refueled. With a change of diet, toxic hunger gradually lessens and resolves, allowing individuals to be satisfied eating less.

When you adopt this nutritarian diet, becoming healthy is the first step. You soon find that the symptoms of toxic hunger are gone. Instead, you will eventually experience the feeling of true hunger, which encourages the precise amount of calories required for good health and the maintenance of ideal weight. True hunger serves as an important guide to promote enjoyment of food. It gives us precise signals from our bodies so we know the amount of calories needed to sustain our lean body mass. When we eat when we are hungry, food tastes much better and we are physiologically primed for proper digestion. Hunger, in the true sense of the word, indicates that it is time to eat again.

T

YPICAL

S

YMPTOMS OF

T

OXIC

H

UNGER

Feeling of emptiness in stomach

Gurgling, rumbling in stomach

Dizziness or lightheadedness

Headache

Irritability or agitation

Lack of concentration

Nausea

Shakiness

Weakness or fatigue

Impairment in psychomotor, vigilance, and cognitive performances

Â

T

YPICAL

S

YMPTOMS OF

T

RUE

H

UNGER

Throat and upper chest sensation

Enhanced taste sensation

Increased salivation

The critical message is that the wrong food choices lead to withdrawal symptoms that are mistaken for hunger. You can always tell that these are toxic hunger symptoms because you experience shakiness, headaches, weakness, and abdominal cramps or spasms. Initially, these symptoms are relieved after eating, but the cycle simply starts over again with the symptoms returning in a matter of hours. Eating when you experience toxic hunger is not the answer. Changing what you eat to stop toxic hunger is.

When our bodies become acclimated to noxious or toxic agents, it is called addiction. If we try to stop taking nicotine or caffeine, we feel ill. This is called withdrawal. When we stop doing something harmful to ourselves, we feel ill because the body attempts to mobilize cellular wastes and attempts to repair the damage caused by the exposure. If we drink three cups of coffee a day, we would get a withdrawal headache when our caffeine level dipped too low. When we consume more caffeine again, we feel a little better because it retards detoxification, or withdrawal. In other words, the caffeine withdrawal symptoms can contribute to our drinking more caffeine products.

Similarly, toxic hunger is heightened by the consumption of caffeinated beverages, soft drinks, and processed foods. Toxic hunger appears after a meal is digested and the digestive track is empty, and it can feel extremely uncomfortable, which can make us think we need to eat or drink a caloric load for relief.

The confusion about food-addictive behavior is compounded because when we eat the same heavy or unhealthful foods that are causing the problem to begin with, we initially feel better. This makes becoming overweight inevitable, because if we stop digesting food, even for a short time, our bodies will begin to experience symptoms of detoxification or withdrawal from our unhealthful diet. To counter this, we eat heavy meals, eat too often, and keep our digestive track overfed to lessen the discomfort from our stressful diet style. In other words, we keep eating too often and too much to postpone or mitigate the physical discomfort caused by our bad diet.

The glucose absorbed right after a meal is called postprandial glucose. After the carbohydrates from the meal are broken down to simple sugars and eventually utilized or stored in the body, most of the glucose not burned is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscle tissues. Glucose is continually utilized to fuel our cells and especially our brain. Our brain use makes up 80 percent of our caloric needs in the resting state. After the meal's contribution is utilized and digestion ceases, we start to gradually burn down our candle of stored glycogen in the liver as our glucose source. This catabolic or breakdown phase, when stored glycogen is our main source of glucose, is called glycolysis. When glycogen stores are being burned for glucose, toxins are better mobilized for removal and repair activities are heightened. Spending time in glycolysis, while resting the digestive apparatus in this non-feeding stage, is important for health and a long life.

But Americans, and especially diabetics, become uncomfortable when beginning glycolysis. They don't feel right if they delay eating too long. This is an important reason why they became diabetic to begin with. They must overeat to feel okay. Just like a person addicted to tobacco must smoke cigarettes just to feel okay, they have become addicted to their dangerous and toxic diet habits and they can't tolerate the symptomatic detoxification events that occur during glycolysis.

Most often these uncomfortable symptoms occur simultaneous to our blood sugar decreasing and glycolysis beginning, but they are not caused by hypoglycemia. While we feed off glycogen stores, rather than actively digest and assimilate glucose, our bodies cycle into heightened detoxification activityâso these sick feelings that accompany glycolysis are a result of tissue sensitivity to mobilization of waste products, which occurs when most active digestion is finished. They occur when the blood sugar is at its lower plateau. These symptoms are obviously not merely caused by low blood sugar, though the symptoms occur in parallel with lower blood sugar.

Gluconeogenesis is the breakdown of muscle tissue to fabricate glucose after glycogen stores have been depleted. As the liver's glycogen stores are utilized and diminish, true hunger signals the need for calories before muscle breakdown begins, thus preventing the onset of gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenesis becomes activated after the glycogen stores have been depleted, so if fasting is continued too long, the body would utilize muscle tissue as a glucose source. Does the body want to waste muscle to maintain our glucose levels? Of course not. We get a clear signal to eat before that begins. I call this clear signal true hunger. True hunger is protective of our muscle mass and gives a clear signal to eat before the beginning of gluconeogenesis, as the glycogen stores are running low and glycolysis is winding down.

Phytonutrients are required for the body to properly detoxify metabolic waste products as they enable cellular detoxification. Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or easily repair the resulting damage. This oxidative stress from the buildup of toxins leads to diseases, including most of the conditions commonly considered the complications of diabetes.

All forms of life maintain a reducing environment within their cells. That means they are continually removing wastes and removing free radicals. Disturbances in this normal redox state occur from micronutrient deficiencies and can cause toxic effects through the production of peroxides and free radicals, which damage all components of the cell. When oxidative stress occurs, certain by-products are left behind and are excreted by the body, mostly in the urine. These by-products are oxidized DNA bases, lipid peroxides

,

and malondialdehyde from damaged lipids and proteins. The higher the levels of these various markers (which can be measured in the urine), the greater the damage to the cellsâmarking the advancement of an oxidative stress-induced disease.

The mammalian circadian system is organized in the brain's hypothalamus. This section of the brain synchronizes cellular oscillators in most peripheral body cells. The liver glucose sensor activates these parts of the brain involved in cellular cycles. Fasting-feeding cycles accompanying rest-activity rhythms are the major timing cues in the synchronization of most peripheral clocks, especially metabolic activity and cellular detoxification. Detoxification efforts of the body vary cyclically and correspond with the rhythm and repetitive timing of sleeping and eating. The deactivation of noxious food components by hepatic, intestinal, and renal detoxification systems is among the metabolic processes regulated in a cyclic manner. The detoxification output of by-products is enhanced during cyclic periods corresponding with glycolysis.

5

This means that when we are not digesting food, the body is in an enhanced repair and detoxification cycle.