The Essential Book of Fermentation (42 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

1 teaspoon honey

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 cup warm spring or filtered water

Heavy cream for brushing tops, if desired

1.

Make the starter: Place the flour in a large bowl and make a well in the center. Pour the kefir into the well.

2.

Bring flour from around the well into the kefir and mix until it’s thoroughly incorporated. Then turn it onto a lightly floured board and knead until it’s smooth and elastic, about 5 minutes.

3.

Place it back into the bowl and cover the bowl with a damp clean dishcloth or plastic wrap.

4.

The next day, knock it down and set it aside to use in your favorite bread recipe, or continue with the recipe to make your bread.

5.

Make the bread: Place the starter in a large bowl and add the flour, salt, yeast, honey, and oil. Add the water a little at a time until you have a smooth dough for kneading.

6.

Knead the dough for 8 minutes, or until it’s smooth and elastic, then cover the bowl with a damp cloth and allow it to rise in a warm place until it’s doubled in size; the time will depend on the temperature.

7.

Punch down the dough, replace the cloth, and let it rise until doubled again.

8.

Grease 3 or 4 loaf pans and divide the dough into 3 or 4 parts. Spray pieces of plastic wrap with nonstick cooking spray and let them settle over the pans, oiled side down against the top of the dough.

9.

Preheat the oven to 425ºF.

10.

When the dough is nicely raised, make a slice or two diagonally across the top of the dough with a scalpel, razor blade, lame, or extremely sharp knife with quick gentle strokes so you don’t collapse the dough. Brush the tops with cream if you wish, but not in the slashes, and bake for 35 minutes for 4 loaves or 40 to 45 minutes for 3 larger ones, or until a loaf sounds hollow when pulled from a pan and tapped on the bottom. Cool on a wire rack.

Pizza Dough

This dough requires a starter that is going at peak power. See the

starter recipe

to get your starter up to speed. While the microbes are killed off during the bake, you still get the benefit of their metabolic products along with your gooey pizza.

Makes 1 large pizza dough

1½ cups

sourdough starter

5 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

½ teaspoon sea salt

About 1½ cups all-purpose flour

1.

In a bowl, mix the sourdough starter, 1 tablespoon of the olive oil, the salt, and 1 cup of the flour. Work more flour into the dough a little at a time until a smooth dough is formed. How much flour is used depends on how wet your starter is.

2.

When you achieve a smooth, pliable dough, set the bowl aside for 30 minutes.

3.

Place a pizza screen or baking sheet in the oven and preheat to 500ºF. On a lightly floured board, roll the dough into a circle, using only the minimum flour to prevent the dough from sticking.

4.

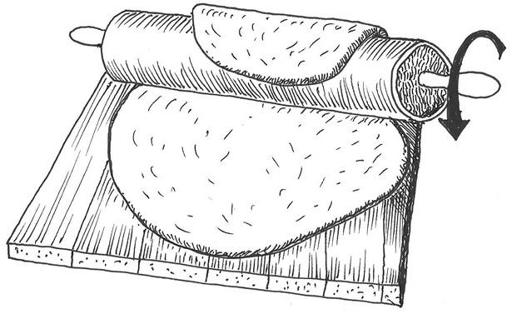

Lay the rolling pin near one edge of the dough and flip the edge toward you, over the pin. Roll up the circle of dough onto the pin. Open the oven door and unroll the dough onto the pizza screen or baking sheet. Close the door and bake for 7 minutes.

5.

Take the crust on its screen or baking sheet from the oven and brush its top surface all over with the remaining olive oil. This prevents the toppings from dribbling juices into the crust and making it soggy. Add your toppings and return the pizza to the oven on its screen or sheet and bake until the cheese melts, the edges of the dough are nicely browned, and the toppings are cooked.

Kishk el Khameer

Kishk el khameer is a lacto-fermented form of bulgur, although sometimes small North African couscous is used. As the bacilli work on the cracked wheat, and as it’s kneaded frequently over many days, it takes on a cheesy aroma, a tangy flavor, and a texture like goat cheese. It originated in the Middle East probably millennia ago, although written records of it date to the thirteenth century. Poor farmers made kishk with water, but wealthier people kneaded the bulgur with yogurt, and today some people recommend making it with kefir or buttermilk.

Kishk el khameer is a traditional food in south Lebanon, and it has come to the attention of Slow Food and been added to that organization’s presidium list as an endangered food that’s being commercially produced. Vegans have discovered it, when made with water, as a non-dairy substitute for cheese.

It is made into two forms. The fresh form, called green kishk, can be used as soon as it ripens, or it can be rolled into little balls the size of large marbles and stored in olive oil. A second form is made by drying it in an oven with a pilot light, in a food dehydrator, or on a roof where the climate is sunny and dry. Think of the climate of Lebanon or Southern California. In humid regions, mold will grow on it, ruining the batch. When dry, it’s crushed into a powder that’s used as a flavor and thickening agent for soups and stews.

I’ve made it with kefir and found that the balls stored in oil make a nice addition to tabouleh. They have a very distinctive and pleasant flavor. In the village of Majdelyoun in southern Lebanon, where small amounts are made commercially, it is flavored with herbs and spices. The following recipe omits the flavorings so that you can taste it in its basic form, but feel free to experiment, especially with the herbs of the dry Mediterranean countries: thyme, rosemary, oregano, and sage.

Makes about 18 balls

1 cup filtered water,

yogurt

, or

kefir

½ cup bulgur or couscous

1 tablespoon sea salt

1.

Place the liquid in a ceramic bowl and mix in the bulgur. Cover with a clean dish towel.

2.

Stir the mixture once a day for 8 days, recovering it with the towel each time.

3.

At the end of 8 days, add the salt and knead it into the kishk.

4.

Place the kishk into a sealed container kept at room temperature and take out the dough to knead it for a few minutes every other day for 30 days. At the end of this period, it should be ripe.

5.

Use it fresh or roll it into balls the size of marbles, place them in a sealed container, and cover them with olive oil for storage. Store in the fridge to stop further ripening.

Injera

In Ethiopia and Eritrea, in East Africa, this spongy, sour flatbread is used to scoop up saucy meat and vegetable dishes, much as naan is used with Indian food. Injera is also used to line the plates on which the stews are served, and its bubbly texture soaks up and holds the juices. When the stews are all picked up by torn pieces of injera and the plate liner is torn apart and eaten, the meal is over.

Injera is made with teff

,

a tiny, round grain that flourishes in the highlands of Ethiopia. While teff is very nutritious, it contains practically no gluten. This makes teff ill-suited for making raised bread, but perfect for folks who are gluten intolerant, so if you are gluten intolerant, use 100 percent teff flour in this recipe. Teff flour can be hard to find in some regions, but check a well-stocked health food store, Whole Foods, or order online at www.myspicesage.com. It is also fermented, but without the leavening properties that wheat gluten imparts. Fermentation with yeast gives it an airy, bubbly texture, and also a slightly sour taste that I would guess is caused by the presence of lactobacilli along with yeast.

The injera served in many East African restaurants here in the States often includes both teff and wheat flour. Most injera made in Ethiopia and Eritrea, on the other hand, is made solely with teff. I know an Eritrean family who lives in San Pablo in the East Bay region of San Francisco, and the very lovely woman who makes injera at home complains that whether she uses all teff or teff and wheat flour, it just doesn’t taste like it does in Eritrea.

Well, sourdough bread made in Chicago won’t taste like the San Francisco kind, either. The flavors of injera and sourdough and many other breads are dictated in large part by the indigenous microbes floating in the air as well as the ingredients.

Like making pancakes, the first one may not be perfect, but you’ll soon have the hang of it. Serve with browned lamb or beef chunks, or boned chicken chunks, in a curry or tikka masala sauce with Sriracha sauce to spice it up.

Makes 4 to 6 injera

½ cup teff flour

½ cup all-purpose flour

1 cup water

Pinch of salt

Peanut or vegetable oil

1.

Place the teff flour in a large bowl. Sift on the all-purpose flour and stir to mix. Add the water, stirring constantly to avoid lumps, until a smooth mixture is formed.