The Essential Galileo (8 page)

Now let me review the observations I made during the past two months, again calling the attention of all who are eager for true philosophy to the beginnings of great contemplations.

[§1.4] Let me speak first of the surface of the moon that is turned toward us. For the sake of being understood more easily, I distinguish two parts in it, which I call respectively the brighter and the darker. The brighter part seems to surround and pervade the whole hemisphere; but the darker part, like a sort of cloud, stains the moon's surface and makes it appear covered with spots. Now these spots, as they are somewhat dark and of considerable size, are plain to everyone, and every age has seen them. Thus I shall call them

great

or

ancient

spots, to distinguish them from other spots, smaller in size, but so thickly scattered that they sprinkle the whole surface of the moon, especially the brighter portions of it. The latter spots have never been observed by anyone before me. From my observation of them, often repeated, I have been led to the opinion which I have expressed; that is, I feel sure that the surface of the moon is not perfectly smooth, free from inequalities and exactly spherical (as a large school of philosophers holds with regard to the moon and the other heavenly bodies), but that on the contrary it is full of inequalities, uneven, [63] full of hollows and protuberances, just like the surface of the earth itself, which is varied everywhere by lofty mountains and deep valleys. The appearances from which we may gather this conclusion are the following.

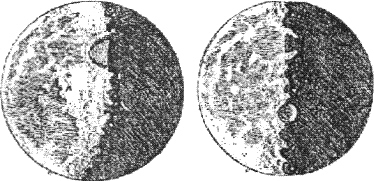

On the fourth or fifth day after the new moon, when the moon presents itself to us with bright horns, the boundary that divides the dark part from the bright part does not extend smoothly in an ellipse, as would happen in the case of a perfectly spherical body, but it is marked out in an irregular, uneven, and very wavy line, as represented in the figure given. Several bright excrescences, as they may be called, extend beyond the boundary of light and shadow into the dark part, and on the other hand pieces of shadow encroach upon the bright.

Furthermore, a great quantity of small blackish spots, altogether separated from the dark part, sprinkle everywhere almost the whole space that is at the time flooded with the sun's light, with the exception of that part alone which is occupied by the great and ancient spots. I have noticed that the small spots just mentioned have this common characteristic always and in every case: that they have the dark part towards the sun's position, and on the side away from the sun they have brighter boundaries, as if they were crowned with shining summits. Now we have an appearance quite similar on the earth at sunrise, when we behold the valleys, not yet flooded with light, but the mountains surrounding them on the side opposite to the sun always ablaze with the splendor of its beams; [64] and just as the shadows in the hollows of the earth diminish in size as the sun rises higher, so also these spots on the moon lose their blackness as the illuminated part grows larger and larger.

However, not only are the boundaries of light and shadow in the moon seen to be uneven and sinuous, butâand this produces still greater astonishmentâthere appear very many bright points within the darkened portion of the moon, altogether divided and broken off from the illuminated area, and separated from it by no inconsiderable interval; they gradually increase in size and brightness, and after an hour or two they become joined on to the rest of the bright portion, now become somewhat larger. But in the meantime others, one here and another there, shooting up as if growing, are lighted up within the shaded portion, increase in size, and at last are linked on to the same luminous surface, now still more extended. An example of this is given in the same figure. Now, is it not the case on the earth before sunrise that while the level plain is still in shadow, the peaks of the most lofty mountains are illuminated by the sun's rays? After a little while, does not the light spread further while the middle and larger parts of those mountains are becoming illuminated; and finally, when the sun has risen, do not the illuminated parts of the plains and hills join together? The magnitude, however, of such prominences and depressions in the moon seems to surpass the ruggedness of the earth's surface, as I shall hereafter show.

And here I cannot refrain from mentioning what a remarkable spectacle I observed while the moon was rapidly approaching her first quarter, a representation of which is given in the same illustration given above. A protuberance of the shadow, of great size, indented the illuminated part in the neighborhood of the lower cusp. When I had observed this indentation a while, and had seen that it was dark throughout, finally, after about two hours, a bright peak began to arise a little below the middle of the depression. This gradually increased, and presented a triangular shape, but was as yet quite detached and separated from the illuminated surface. Soon around it three other small points began to shine. Then when the moon was just about to set, that triangular figure, having now extended and widened, began to be connected with the rest of the illuminated part, and, still girt with the three bright peaks already mentioned, suddenly burst into the indentation of shadow like a vast promontory of light.

Moreover, at the ends of the upper [65] and lower cusps certain bright points, quite away from the rest of the bright part, began to rise out of the shadow, as is seen in the same illustration. In both horns also, but especially in the lower one, there was a great quantity of dark spots, of which those that are nearer the boundary of light and shadow appear larger and darker, but those that are more remote less dark and more indistinct. In all cases, however, as I have already mentioned before, the dark portion of the spot faces the direction of the sun's illumination, and a brighter edge surrounds the darkened spot on the side away from the sun and towards the region of the moon in shadow. This part of the surface of the moon, where it is marked with spots like a peacock's tail with its azure eyes, looks like those glass vases that, through being plunged while still hot from the kiln into cold water, acquire a crackled and wavy surface, from which circumstance they are commonly called frosted glasses.

Now, the great spots of the moon observed at the same time are not seen to be at all similarly broken, or full of depressions and prominences, but rather to be even and uniform; for only here and there some spaces, rather brighter than the rest, crop up. Thus, if anyone wishes to revive the old opinion of the Pythagoreans, that the moon is another earth, so to speak, the brighter portions may very fitly represent the surface of the land, and the darker the expanse of water; indeed, I have never doubted that if the sphere of the earth were seen from a distance, when flooded with the sun's rays, the part of the surface which is land would present itself to view as brighter, and that which is water as darker in comparison. Moreover, the great spots in the moon are seen to be more depressed than the brighter areas; for in the moon, both when crescent and when waning, on the boundary between the light and the shadow that is seen in some places around the great spots, the adjacent regions are always brighter, as I have indicated in drawing my illustrations; and the edges of the said spots are not only more depressed than the brighter parts, but are more even, and are not broken by ridges or ruggedness. But the brighter part stands out most near the spots so that both before the first quarter and near the third quarter also, around a certain spot in the upper part of the figure, that is, occupying the northern region of the moon, some vast prominences on the upper and lower sides of it rise to an enormous elevation, as the following illustrations show.

This same spot before the third quarter is seen to be walled around with boundaries of a deeper shade, which, just like very lofty [66] mountain summits, appear darker on the side away from the sun, and brighter on the side where they face the sun. But in the case of cavities the opposite happens, for the part of them away from the sun appears brilliant, and the part that lies nearer to the sun dark and in shadow. After a time, when the bright portion of the moon's surface has diminished in size, as soon as the whole or nearly so of the spot already mentioned is covered with shadow, [67] the brighter ridges of the mountains rise high above the shade. These two appearances are shown in the following illustrations.

There is one other point which I must on no account forget, and which I have noticed and rather wondered at. [68] It is this. The middle of the moon, as it seems, is occupied by a certain cavity larger than all the rest, and in shape perfectly round. I have looked at this depression near both the first and third quarters, and I have represented it as well as I can in the two illustrations given above. It produces the same appearance with regard to light and shade as an area like Bohemia would produce on the earth, if it were shut in on all sides by very lofty mountains arranged on the circumference of a perfect circle; for this area in the moon is walled in with peaks of such enormous height that the furthest side adjacent to the dark portion of the moon is seen bathed in sunlight before the boundary between light and shade reaches halfway across the circular space. But according to the characteristic property of the rest of the spots, the shaded portion of this too faces the sun, and the bright part is towards the dark side of the moon, which for the third time I advise to be carefully noticed as a most solid proof of the ruggedness and unevenness spread over the whole of the bright region of the moon. Of these spots, moreover, the darkest are always those that are near to the boundary line between the light and the shadow, but those further off appear both smaller in size and less decidedly dark; so that finally, when the moon at opposition becomes full, the darkness of the cavities differs from the brightness of the prominences by a modest and very slight difference.

These phenomena which we have reviewed are observed in the bright areas of the moon. In the great spots, we do not see such differences of depressions and prominences as we are compelled to recognize in the brighter parts owing to the change of their shape under different degrees of illumination by the sun's rays, according to the manifold variety of the sun's position with regard to the moon. Still, in the great spots there do exist some areas rather less dark than the rest, as I have noted in the illustrations; but these areas always have the same appearance, and the depth of their shadow is neither intensified nor diminished; they do appear indeed sometimes slightly darker and sometimes slightly brighter, according as the sun's rays fall upon them more or less obliquely; and besides, they are joined to the adjacent parts of the spots with a very gradual connection, so that their boundaries mingle and melt into the surrounding region. But it is quite different with the spots that occupy the brighter parts of the moon's surface, for, just as if they were precipitous mountains with numerous rugged and jagged peaks, they have well-defined boundaries through the sharp contrast of light and shade. [69] Moreover, inside those great spots, certain other areas are seen brighter than the surrounding region, and some of them very bright indeed; but the appearance of these, as well as of the darker areas, is always the same; there is not change of shape or brightness or depth of shadow; so it becomes a matter of certainty and beyond doubt that their appearance is due to the real dissimilarity of parts, and not to unevenness only in their configuration, changing in different ways the shadows of the same parts according to the variations of their illumination by the sun; this really happens in the case of the other smaller spots occupying the brighter portion of the moon, for day by day they change, increase, decrease, or disappear, inasmuch as they derive their origin only from the shadows of prominences.