The Everything Mafia Book (5 page)

Philadelphia had its own Irish mob group. The K&A Gang, headquartered in northeast Philly, were a loose-knit gang of Irish-American mobsters who dealt drugs and ran sophisticated burglary rings through the 1990s.

Wild Bill

The leader of the White Hand gang was a young, wide-eyed upstart who rose to the top in the usual gangland way, by murdering his former boss. Wild Bill Lovett saw the Italian gangs across the river as his biggest challenge, rather than other Irish mobsters. But his reign over the underworld scene on the docks was short-lived. Less than five years after becoming the boss of the White Hand he was shot and had a meat cleaver sunk into his skull. Needless to say that took care of Wild Bill, and the White Hand soon followed.

The Killer Irishman

The most successful and ruthless of the New York Irish gangsters in the 1930s was a tough mug called Owney “the Killer” Madden. He was a dapper man who partied in the high society of the day. He had interests in the bootleg racket and was the owner of the legendary Harlem nightclub called the Cotton Club. Lucky Luciano treated him with respect, and they did business amicably.

Madden did a year in the slammer and then retired to Hot Springs, Arkansas. This was a Mafia resort town discovered by Al Capone, and it is famed for its natural and restorative mineral baths. Gangsters put it on the map, and now ordinary citizens still flock there to “take in the waters” and gamble at the world-famous racetrack, Oaklawn Park.

The Westies rarely ventured from their tight-knit neighborhood, preferring to run their operations out of Irish pubs and back alley clubs. Coonan, however, led the suburban life in New Jersey, commuting into New York City each morning.

The Westies

The Irish mob’s last stand in New York took place in Hell’s Kitchen, a working-class neighborhood on the West Side of Manhattan. The longtime boss Mickey Spillane (no relation to the writer) was killed on March 13, 1977. Jimmy Coonan replaced him. Jimmy’s tenure as head of the Westies was one of violence and brutality. He lacked the finesse of his elders. His gang was more like a crew of out-of-control street punks than a sophisticated organized crime family. They drank too much and also indulged in the drugs they pushed.

Coonan and his cronies had a penchant for chopping the hands off those they murdered. There were no fingerprints to identify the body that way. One assumes he was too brazen to consider that the cops might use dental records to get the deceased’s identity. He was certainly on the right track, however.

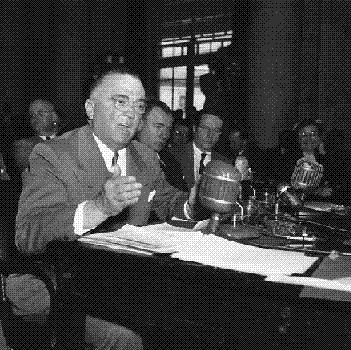

Owney Madden

Courtesy of AP Images

Owney Madden, left, suspected but unconvicted racketeering boss, is escorted by detective Thomas Horan shortly after Madden was ordered on Febuary 13, 1932, to report to Sing Sing as a possible parole violator. He was en route to the Tombs Prison in New York pending a hearing two days later.

Owney Madden, left, suspected but unconvicted racketeering boss, is escorted by detective Thomas Horan shortly after Madden was ordered on Febuary 13, 1932, to report to Sing Sing as a possible parole violator. He was en route to the Tombs Prison in New York pending a hearing two days later.

There were more than thirty unsolved murders in Hell’s Kitchen in the 1970s through the mid-1980s that had the mark of the Westies. Coonan was ultimately convicted under the RICO Act and sentenced to seventy-five years.

Climbing the Ladder

The early slum gangs gave rise to homegrown crime groups, while immigrant mobsters joined in the noxious mix. Throw in Jewish and Irish racketeers in New York, Polish and black racketeers in Chicago, Cuban and Anglo racketeers in Tampa, and the early underworld scene was a multiethnic jumble. The power quickly shifted to the Italian crime gangs, the Camorra, and the Mafia. But after a bloody war for control, the Mafia became the main Italian crime group in the poor ethnic slums. But they would not stay there for long.

During the infamous Mafia-Camorra wars that ran from 1914 to 1918, the Mafia was headquartered in Manhattan, while the Camorra had their largest operations in Brooklyn. There was a series of tit-for-tat retaliatory hits, leading up to the execution of one of the Camorra hit men by the State of New York, one of the few mobsters ever executed for murder.

The Mafia in Sicily

The Mafia continued to be a powerful and dangerous force in Sicily after it branched off to set up shop in America. The Sicilian and American Mafia families formed alliances, had feuds, and did business together. While the Mafia in Sicily was distinctly separate from its cohorts in crime, the American melting pot brought them together. While poverty brought many hardworking immigrants from Italy to America, some of the criminals came by way of force.

Il Duce

Benito Mussolini was the fascist dictator of Italy from 1922 until his assassination during World War II. It was to be expected that a totalitarian dictator and an organized crime family would not get along together. Like rivals in a Wild West town, the island of Sicily was not big enough for both of them.

During one of Mussolini’s many parades, this one through a Sicilian town, the local don, who felt this dictator was unworthy of respect, ordered the townspeople not to come out and line the parade route in tribute. To add to the flagrant disrespect, he had several bedraggled homeless men amble into the square to hear the dictator’s bombastic and bellicose ranting. The bullet-headed Mussolini was furious and launched a crackdown on the Mafia. When he was done, many were dead and most of the major dons were behind bars. Ultimately, however, the Mafia would have the last laugh, with a little help from Uncle Sam.

Mussolini did not have a chance to fully rid Sicily of the Mafia. His alliance with Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany launched Italy into World War II. The feud between the Sicilian Mafia and the dictator Mussolini inspired the Americans to side with the Mafia. Sicilian Mafiosi spied for the Americans during the Allied invasion of Sicily, and after they kicked the Germans off the island, they allowed the Mafiosi to come into positions of authority.

CHAPTER 3

The First Family of the American Mafia

People usually associate the beginning of the Mafia with the Roaring Twenties and the rat-a-tat-tat of Tommy guns in Chicago or New York. But the word

Mafia

came into national consciousness in 1891 in the Deep South. New Orleans may be the birthplace of the American Mafia. The land of jambalaya and crayfish was a sweltering melting pot of various ethnic groups, including Sicilians. And on the docks emerged the first vestiges of the Mafia in America.

Coming to New Orleans

Italian immigrants came to America in great numbers in the last decades of the nineteenth century. From 1860 to 1890 thousands of Sicilians came to New Orleans, Louisiana. Both criminals and noncriminals alike encountered racism from the locals; the city was not used to the darker-skinned Sicilians. But there was a Mafia element that fed on the fear. The Mafia element went into the shadows, functioning in the nooks and crannies of the culture. This was their comfort zone. In the periphery they banded together and made plans.

The mayor of New Orleans, Joseph Shakespeare, did not like the wave of Sicilian immigration and spoke against them in no uncertain terms. He called them “vicious and worthless,” adding, “They are without courage, honor, truth, pride, religion, or any quality that goes to make good citizens.” He even made the threat, “I intend to put an end to these infernal Dago disturbances, even if it proves necessary to wipe out every one of you from the face of the earth.”

Emergence

New Orleans was the first foothold of the Mafia in America. The families that formed later in New York, Chicago, and other big and small cities have become very well known, and the Mafia is usually associated with Northern urban types, but the Southern Mafia family was here first. The port city of New Orleans was an ideal place to begin its crooked business dealings.

A port city was ideal for the Mafia’s penchant for muscling in on trade and commerce, and demanding “protection money.”

The Black Hand Revisited

The Mafia gangs used the “Black Hand” technique to extort money from their own kinsmen. A politely written note would be left for the merchant or businessman stating that money was expected at a certain date/time or he would be brutally killed. The bizarre Old-World gentility of the letter’s wording contrasted with the threats of violence. This was no bluff. People were beaten, businesses trashed, and families killed if they did not make a prompt payment to the sender. The signature of the letter was a black palm print, hence the name “Black Hand.”