The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book (34 page)

Read The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book Online

Authors: Arthur G. Sharp

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

B. distantly related to the Roosevelts.

C. experienced as a botanist and horticulturalist.

D. the former president of Cornell College in Iowa.

13-3 John Burroughs was:

A. the author of the Tarzan books.

B. author Edgar Rice Burroughs’s twin brother.

C. a nature writer and essayist in the 1800s and 1900s.

D. opposed to fishing for sport.

13-4 The Antiquities Act passed by Congress in 1906 was designed to:

A. protect the elderly.

B. set fixed prices at antiques shops in the Western United States.

C. make sure that no person over age sixty-six could be elected as president of the United States.

D. establish that archeological sites on public lands are important public resources.

13-5 Which of these activities was TR not fond of?

A. fishing

B. hunting

C. horseback riding

D. writing letters to his children

ANSWERS

13-1. True: Although McGee was well versed in numerous scientific fields, the only college degree he had was an honorary degree from Cornell College in 1901.

13-2. C

13-3. C

13-4. D

13-5. A: John Burroughs said that one of the differences between him and TR was that Burroughs enjoyed fishing, while TR did not.

CHAPTER 14

The Nonpolitical Years

“This country will not be a good place for any of us to live in if it is not a reasonably good place for all of us to live in … Laws are enacted for the benefit of the whole people, and must not be construed as permitting discrimination against some of the people.”

TR hit the ground running after he left the White House in 1909. He led an eleven-month safari to East Africa and followed that with a three-month sojourn through Europe. TR visited a few countries with no specific agenda, except for picking up his Nobel Peace Prize in Norway. Once he returned to the United States, he limited his activities to a few speeches, writing, and relaxing with his family. It was a restful period, especially for someone as energetic as TR. His hibernation was the calm before the storm.

Leading a Safari

TR was out of office with no particular plans. Sitting idle was never one of his favorite pastimes. He needed something meaningful to do. The Smithsonian Institution came to the rescue and asked him to lead a scientific expedition to British East Africa, which lasted from April 21, 1909, to March 14, 1910.

The cost of the expedition was $100,000 (about $2.5 million in 2010 terms), or about $8.77 per specimen collected. (The number of specimens collected was 11,397.) The Smithsonian paid half, which it generated from requests for donations. TR added $25,000, as did Andrew Carnegie. The party included two guides, two zoologists, a physician, a photographer (Kermit), and a “bwana,” or boss (TR).

Technically, TR was the leader, but in name only. The true leader was R. J. Cunninghame (alternately spelled Cunningham), a guide from the expedition’s outfitter, Newland & Tarlton. But TR was the star of the trip. Without him, the safari might have been just one more expedition to Africa. Because it was him and he was still riding a wave of post-presidency popularity, his trip started a rash of safaris among adventurers who could afford the hefty cost.

TR was grateful for the opportunity. It gave him the chance to further his knowledge of natural history, hunt big game, and spend quality time with his son Kermit.

While in Africa, TR started coming face-to-face with his own mortality and the passing of the torch. Again, while talking about Kermit, this time in a letter to Ethel, he wrote about their last hunt together. They were successful.

Between them, they shot three giant eland. “We worked hard,” TR wrote. “Kermit of course worked hardest, for he is really a first-class walker and runner; I had to go slowly, but I kept at it all day and every day.” He still had the will. Some of his famed energy was lacking.

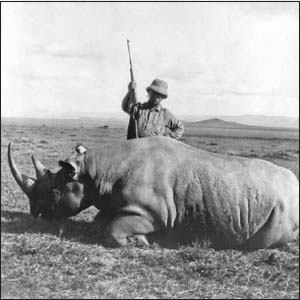

Theodore Roosevelt and his big bull rhino

TR and Kermit combined killed 512 animals during their safari, including seventeen lions, eleven elephants, and twenty rhinoceroses. Once, while TR was standing over a freshly killed eland, a guide told him about a rhinoceros standing nearby. He rushed over and shot it, too. That was how hunters gathered “specimens” in those days.

TR had always wanted to take a safari such as this one. But it provided more proof to some of his detractors that he wanted to shoot wildlife, not catalog it. He told the audience at his November 18, 1910, presentation to the National Geographic Society:

Really, I would be ashamed of myself sometimes, for I felt as if I had all the fun. I would kill the rhinoceros or whatever it was, and then [the scientists] would go out and do the solid, hard work of preparing it. They would spend a day or two preserving the specimens, while I would go and get something else

.

In TR’s final report to the Smithsonian, he gives the credit for the safari to the other members: “The invertebrates were collected carefully by Dr. Mearns, with some assistance from Messrs. Cunningham and Kermit Roosevelt … Anthropological materials were gathered by Dr. Mearns with some assistance from others; a collection was contributed by Major Ross, an American in the government service at Nairobi,” etc. His report made it sound as if he did not do any of the work, which was rarely the case with TR.

Homesick

As much as TR was enjoying himself, he was tiring of the safari by the end of the year, especially as Christmas arrived. He told Ethel in a letter written two days before Christmas that, “I am so eagerly looking forward to the end, when I shall see darling, pretty Mother, my own sweetheart, and the very nicest of all nice daughters—you blessed girlie.” He did not have much longer to wait.

Eventually, TR had to leave and find some other projects to attack. The safari ended in March 1910; he was left with a lot of time on his hands and nothing to do with it.

The safari piqued TR’s curiosity. He wrote: “I wish field naturalists would observe the relation of zebras and wild dogs … It seemed to us that zebras did not share the fear felt by the other game for the dogs.” There were questions he wanted answers to, but he could not answer himself. The same curiosity he exhibited as a child came to the fore in Africa.

TR allowed that he had never passed a more interesting eleven months than those he spent in Africa, especially from the standpoint of a scientist. However, it was time for a new adventure. Europe seemed like a good place to find one—especially since Edith was going to meet him there.

No Rush to Get Home

TR did not return to the United States immediately. He traveled around Europe for a few months, giving speeches, collecting honoraria, and representing the country at King Edward VII of Great Britain’s funeral.

President Taft asked TR to represent the United States at the funeral of Great Britain’s King Edward VII, who died on May 6, 1910. TR announced to France’s ambassador to Great Britain, Paul Cambon, that he would do so “dressed in khaki and boots with a Buffalo Bill hat and armed with a saber and pistols.” Edith nixed that idea. He rode in a carriage at the funeral and wore a top hat and tails.

He took a side trip to Denmark and Norway in early May to pick up his Nobel Peace Prize, since he was in the area. During his May 5 acceptance speech, the man who had urged the United States to go to war against Spain in 1898 and who would push for its entry into World War I in Europe, declared that, “Peace is generally good in itself, but it is never the highest good unless it comes as the handmaid of righteousness; and it becomes a very evil thing if it serves merely as a mask for cowardice and sloth, or as an instrument to further the ends of despotism or anarchy.”

Three weeks later, he received an honorary membership in the Cambridge Union, Cambridge University’s debating society. TR was in his glory during those days in Europe.