The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (13 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

All the new Republic needed was a leader. The thoughts of Favre and of his fellows immediately turned towards the man whose name had been called out by the mob nearly as often as Rochefort’s:

General Trochu. Over the past few days, Trochu, his bad relations

with the Empress and Palikao hidden from no one, isolated and aloof from it all, the one general whose reputation was still untarnished, had rapidly assumed the stature of a god in Parisian eyes. Far from making any gesture to save the regime (though he had only recently assured the Empress of his fidelity), he had remained locked in his headquarters at the Louvre while the Palais Bourbon was being stormed and had not left it until all was over; later, in his memoirs, blaming Palikao for having kept him completely in the dark. As the mob passed the Louvre on its way to the Hôtel de Ville, Trochu rode out on horseback and soon spotted Favre’s tall figure with its great head of hair. Favre had told him of the invasion of the Corps Législatif, and called upon Trochu to join in the march upon the Hôtel de Ville. Offered the post of President, Trochu accepted it with no great enthusiasm; having first been assured by his future colleagues that they would ‘resolutely defend religion, property and the family’. At a time when the country was involved in a life-or-death struggle, it was perhaps a strange primary consideration.

The remainder of the Government posts were filled amid an almost indecent scramble for spoils on the part of some of the new leaders. Crémieux was observed advancing on the Ministry of Justice in the Place Vendôme as fast as his small legs would carry him, accompanied by a horde of ragamuffins, while Gambetta and Picard—both after the same office—arrived at the Ministry of the Interior simultaneously. Gambetta triumphed, however, through the cunning

de facto

ploy of instantly dispatching telegrams signed ‘The Minister of the Interior, Léon Gambetta’. Favre was appointed Vice-President and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Picard had to content himself with Finance. Étienne Arago became Mayor of Paris. Thiers declined office, and of the extreme Left only Rochefort was brought into the Government. Louise Michel recalled Favre genially greeting Ferré and young Raoul Rigault on the threshold of the Hôtel de Ville as ‘

mes chers enfants

’, but already there were those who wondered how long the peace between the two sets of Republicans would last. Edmond Goncourt for one, though certainly no supporter of Louis-Napoleon, had misgivings about the new regime:

I cannot explain why, but I have no confidence; it does not seem possible to rediscover in this boastful

plebs

these first soldiers of

la Marseillaise

. They seem to me simply cynical cads, full of fun and frolic, playing politics; lads who have no feeling under the left breast for the vast sacrifices of the nation.

Oui, la République

….

One thing was certain; as in the case of past revolutions, France was now ruled by a Government formed by Parisians, of Parisians,

and for Parisians. The views of the rest of the country had never been considered for one moment.

Among his first duties Trochu took it upon himself to notify Palikao of what had transpired. Trochu found a broken man who had just received word that his son had been mortally wounded at Sedan. His head resting between his hands, Palikao hardly seemed to take anything in, and then announced that he was leaving for Belgium. Meanwhile the Empress had already fled. Courageously she had stayed on at the Tuileries that afternoon long after the invasion of the Palais Bourbon, until two old friends, Nigra and Metternich, the Italian and Austrian Ambassadors, had come and urged her to flee. At first she refused. She remembered the humiliation in which Louis XVIII had left, forgetting even his slippers, and how poor old Louis-Philippe and Amélie had scuttled out of these same Tuileries in an open coach, taking only fifteen francs with them, and leaving their dinner to be finished by the revolutionaries. She had long sworn that none of this would happen to her. But it was already late. The servants were beginning to desert their imperial mistress, flinging off their livery and pilfering as they went. The mob gathering outside could be clearly heard within; then a clatter of muskets in the courtyard and rough voices on the main staircase. Fortunately something still held the mob back, perhaps the memory of Louis-Napoleon’s ruthlessness during the

coup d’état

of 1851. The Empress at last consented to leave. It was too late to use the gate on the Place du Carrousel, which was filled with people, so the Empress, accompanied by the two ambassadors and her lady-in-waiting, Madame Lebreton, left by a side door and scurried through the galleries of the Louvre. At the Rue de Rivoli exit the diplomats a little ungallantly placed the two heavily veiled women in a carriage and left them to their fate. At first they went to the house of a State Councillor in the Boulevard Haussmann, but he had already gone. It was the same story at the house of the Empress’s Chamberlain in the Avenue de Wagram. Eventually, in despair, she thought of her American dentist, Dr. Evans, the man who had bought up the Civil War ambulance after it had been shown at the Great Exhibition.

The handsome and popular dentist was at home, entertaining two ladies. At once he offered his services. The next day at dawn he smuggled the Empress out of Paris in his own coach, telling the sentries on the barricades that he had with him ‘a poor woman on her way to a lunatic asylum’. Two days later the party safely reached Deauville, where Dr. Evans persuaded an Englishman, Sir John Burgoyne, to take the Empress over to England. It was an extremely rough passage, and the Empress landed feeling so unwell that she had to be taken to see a doctor; by a strange coincidence it was the same

that had attended the seventy-five-year-old Louis-Philippe after his flight in 1848.

So the Second Empire ended. The faithful Mérimée wrote to Panizzi that day: ‘Everything is collapsing at once’; and six weeks later he died broken-hearted in Cannes. The rest of imperial society made its way, with Palikao, to Brussels; passing

en route

that most famous of returning exiles, Victor Hugo, and his ménage. As they encountered the beaten remnants of the Sedan army, Hugo wept and remarked to his companions: ‘I should have preferred never to return rather than see France so humiliated, to see France reduced to what she was under Louis XVIII!’

In Paris the mob had now occupied the Tuileries, finding all the sad signs of an unintended departure; a toy sword half-drawn on a bed, empty jewel cases strewn on the floor, and on a table some bits of bread and a half-eaten egg. In the time-honoured sequence of French revolutions, the mob quickly set about effacing the traces of the fallen regime. Just as at the onset of the ‘Hundred Days’ the fleurs-de-lis had been unpicked from the Tuileries carpets and replaced with Napoleonic bees, so now all the N’s and imperial eagles were chiselled and ripped off the public buildings, and busts of the deposed Emperor joyfully hurled into the Seine. At the main entrance of the Tuileries, later in the afternoon of September 4th, Goncourt saw scribbled in chalk the words ‘Property of the People’. A young soldier was holding out his shako to the crowd and crying ‘For the Army’s wounded’, while others in white shirts had climbed up the pedestals of the peristyle columns and were shouting out ‘Free entry into the bazaar!’

Throughout the city an atmosphere of unrestrained carnival reigned, and evidently no-one had time to share Goncourt’s sober thoughts about the new regime. It was a sparklingly sunny day, no blood had been shed, and all Paris now turned out in its Sunday best to celebrate the most joyous revolution it had ever had. George Sand, aged sixty-six, rejoiced: ‘This is the third awakening; and it is beautiful beyond fancy…. Hail to thee, Republic! Thou art in worthy hands, and a great people will march under thy banner after a bloody expiation….’ On the afternoon of September 4th, Edwin Child noted how ‘the army fraternized with the citizens, carrying the butt end of their muskets in the air, and the town presented more the appearance of a grand national

fête

, than that of the capital of a country that has just received the shock of the greatest capitulation and defeat known in history’. There were some incredible scenes. Juliette Adam, long an enthusiastic Republican, thought that the Concorde presented ‘a marvellous spectacle’:

From the chestnut trees of the Tuileries just as far as the horizon of Mont-Valérien and the hills bathed by the Seine, the scene is on so grand a scale, the crowd feels such a real communion of ideals and desires, that poetry and enthusiasm invade even the coldest and most insensitive hearts. Everything provokes admiration, everything fascinates the vision of these deeply moved Parisians! Around the lamp posts, red crêpe flutters in the breeze… water gushes and sings in the fountains; the dome of the Invalides glitters in the sun…

On the Pont de la Concorde she noticed a young worker in a red fez who had been singing the Marseillaise non-stop for the past three hours, clinging to one of the candelabra. Amid all the celebration, there was a universal intangible feeling that everything was somehow going to be all right now. All had been the fault of the Emperor and his extraordinary mediocrity—no one else’s, certainly not France’s—and now that had been purged. The new sixteen-year-old wife of Paul Verlaine (whose marriage conscription had postponed) voiced the mystique of

La République

that was so widely shared when she asked, longing for assurance: ‘Now that we have her, all is saved—that’s so, isn’t it? It will be like in…’ ‘Like in ’92, she wanted to say’, explained Verlaine. ‘

They

won’t dare to come now that we have

her

’, a workman said, echoing Madame Verlaine. After all, what quarrel could the Prussians have with poor France, now that she had rid herself of the wicked Bonaparte? What the Parisians could not see in this hour of extraordinary rejoicing was the solid German phalanxes, advancing ever closer, nor hear the German Press at home shrieking for the destruction of ‘the modern Babylon’.

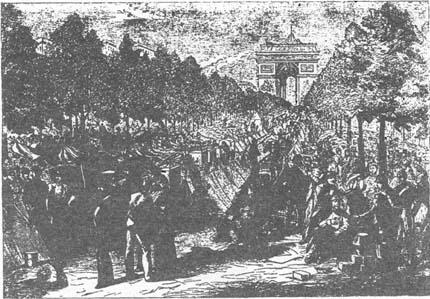

After Sedan: Troops encamped on the Champs-Elysees

4. Paris Prepares

W

HILE

Paris continued to exist in a jubilee atmosphere, effacing the last relics of the Second Empire and, in that time-honoured continental manner, changing street names so that the Rue du 10 Décembre reappeared as Rue du 4 Septembre, the new Government settled down to surveying its assets. With a quarter of a million men captive, one way or another, at Sedan and Metz, little enough remained of the Army Louis-Napoleon had taken to the wars six weeks previously. General Vinoy’s newly formed XIII Corps which, fortunately, had moved too slowly to reach Sedan in time, was now in fact the last major unit left to France. Bedraggled, jaded, and dispirited, its return to Paris had reminded an American observer of the ‘floating in of a wreck upon the beach’. In a letter to their daughter, an English couple wrote ‘There seems nobody here to direct anything—soldiers arriving, worn out with fatigue, and no better rooms to be found for them than a bed on the damp earth in the Avenue de la Grande Armée—not even straw, on which to lay their weary limbs….’ Part of General Vinoy’s corps was also sprawled out in an encampment where that far-away memory, the Great Exhibition of 1867, had once stood. It

contained virtually only two good regular regiments, the 35th and 42nd, which had been recalled from Rome where they had constituted the pontifical guard.

A bric-

à

-brac of other troops escaped from Sedan and elsewhere, numbering perhaps 10,000, made up the total to somewhere over 60,000. There were also 13,000 well-trained naval veterans, including marines and gunners with their weapons, which someone had farsightedly ordered to Paris; as well as a sprinkling of well-disciplined units formed of gendarmes, customs officers, firemen, and even foresters. Then there were a force of over a hundred thousand

Mobiles

, or ‘

Moblots

’, young Territorials from the provinces who had been organized too belatedly to have received more than the sketchiest training. These included twenty-eight battalions of Bretons, many of whom spoke no French and were regarded with contempt by the proletarians of the Paris National Guard (the feeling was mutual), although they were to prove themselves to be among the most reliable of Paris’s defenders. Thus with this concentration of forces upon the capital, Trochu had virtually denuded the rest of France.

Finally, there was the Paris National Guard. At the outbreak of hostilities this had numbered only 24,000 volunteers. Then it was expanded to some 90,000, and the Government of National Defence now vastly augmented it by introducing compulsory registration. Its members were paid 1.50 francs a day and—as a Republican sop to the extreme left-wingers of Belleville—were allowed to elect their own officers. To everyone’s astonishment the enrolment of the National Guard produced some 350,000 able-bodied males; a fact which in itself revealed the inefficiency of France’s war mobilization. What was to be done with this great untrained mass of men? Only a small percentage of them would be required to fill the role for which they were originally intended, that of relieving the regulars and

Mobiles

on the fortifications. And who was to control the unruly elements of the city, now that they had rifles placed in their hands? From the first Trochu and the regular Army generals had doubts about the National Guard’s military value; ‘We have’, said Trochu, ‘many men but few soldiers’. But nobody could then foresee what a terrifying crop would spring from this sprinkling of dragon’s teeth. The force, actual and potential, of over half a million men was supported by more than 3,000 cannon of varying sizes. Some of these guns were mobile field artillery, some were mounted in floating batteries and

chaloupes

1

of the Seine flotilla (they had originally been

designated for service on the Rhine), but about half of the heavy pieces were stationed in the city’s external fortifications. And herein lay Paris’s principal hope of surviving a siege. The whole city was surrounded by an

enceinte

wall, 30 feet high and divided into ninety-three bastions linked with masonry ‘curtains’. In front of the wall was a moat 10 feet wide, and behind ran a circular railway supplying troops to the ramparts. Beyond the moat, at distances varying between one and three miles, lay a chain of powerful forts. There were sixteen in all, each mounting between fifty and seventy heavy guns and each within artillery range of its immediate neighbours. From Vauban’s day until the Maginot Line, the French have been unrivalled in the building of fortifications, and every one of the Paris forts was placed in a superbly commanding position. The most powerful of all was Mont-Valérien, perched on its great hill in the loop of the Seine to the north of St.-Cloud. Today, though the wall has gone and Paris has long since enveloped the line of forts, they still offer fascinating and unexpected panoramas out over the city.

1

Unfortunately, however, the forts which had been built on M. Thiers’s instance in 1840 were already to some extent out of date by 1870. Nothing had been done to incorporate the lessons about plunging fire learned from the Crimea, and worst of all the range of heavy cannon had roughly doubled during the past thirty years. As a result, several of the forts could be commanded by artillery fire from neighbouring heights (notably those of Châtillon at the south), from which parts of the city itself could actually be bombarded. And then, as Viollet-le-Duc, that great restorer of medieval fortresses who was then serving as a colonel of the Engineers pointed out, there was something marvellously anachronistic about a modern city like Paris, in a country as centralized as France, withdrawing into its keep, while abandoning the country at large to the marauders.