The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (67 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

The Rev. Gibson had left Paris to join his wife and family at Chantilly, but M. Chastel, the librarian at his Methodist Chapel in the Rue Roquépine (close to the Place St.-Augustin and the Boulevard Malesherbes), had remained to find himself in the centre of the fighting. In a detailed letter to Gibson, he wrote:

Since eight o’clock this morning there has been a fusillade in our street…. This morning we were surrounded by National Guards, and we heard the fusillade in the direction of the Faubourg St.-Honoré and the Champs-Élysées. After a while the fight was close to Saint-Augustin, in the Boulevard Malesherbes, and at last the soldiers reached our street. We could not even put our nose through the window without the risk of being struck by a ball. The soldiers are installed in the house next to our chapel, and are firing in the direction of the Rue Neuve des Mathurins (in a line with our Rue Roquépine on the other side of the Boulevard Malesherbes). They are at the doorway and at the windows of each storey. You can imagine the noise and confusion we hear outside. About nine o’clock we had worship in our room; all in the house were present, and we prayed earnestly to God to aid us…. I heard a poor wounded man uttering a cry, I peeped out from under our window shutters. We saw him carried off. Shortly afterwards a soldier was killed on the spot close to our library….

Later that afternoon, a

Versaillais

sapper entered the Roquépine Chapel to inform M. Chastel that ‘they have surrounded Paris, and they are about to deliver us from the Commune. After having drunk a glass of wine, he took his post at our chapel door and began firing….’

The fighting soon reached Alan Herbert’s house, about a quarter of a mile further to the east. At one moment the Communards erecting the barricade outside had threatened to search all the houses for able-bodied men to fight, but ‘events were too rapid to allow them

M

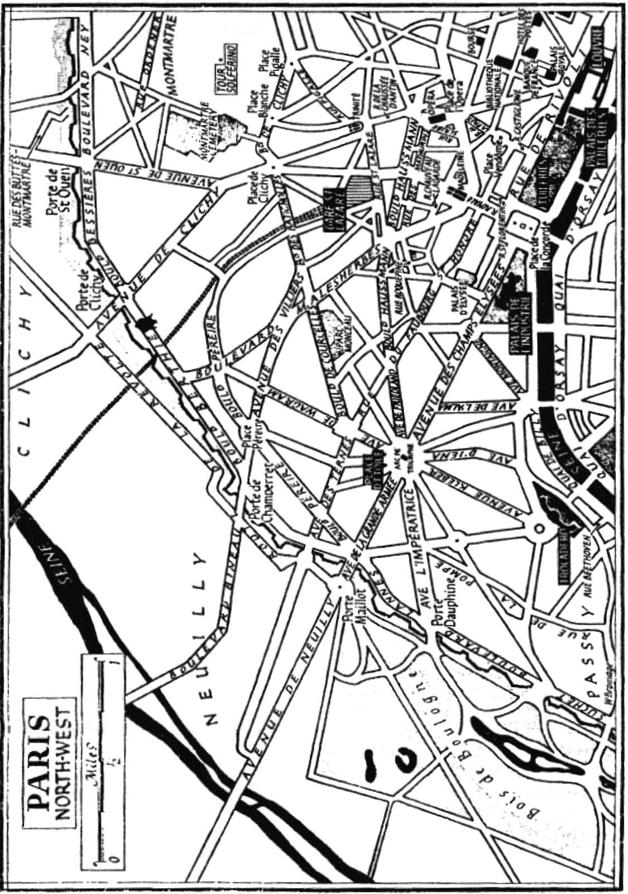

AP

3. Paris: north-west

to do so’. Dr. Herbert had then offered his services—which were not accepted—to a first-aid station set up in the Place de la Madeleine market; the proximity of which ‘was very useful, as I was able to get some food sent to me through a window in my house, which looks upon it’. Two of the National Guards stationed outside declared to Herbert ‘their intention of running away, taking off their regimentals and hiding themselves’. Then, at about 10 a.m.,

the firing became very bad, and cannon were brought up to be planted on the boulevards…. No one dared to stir out, and the sentries knew nothing. Towards the afternoon the fighting in the streets assumed another character. The troops had succeeded in taking posession of a house at the end of my street, Rue Chauveau Lagarde, and made their way from house to house by holes in the walls, till they arrived at the end of the street, and then they fired down on the barricade. The insurgents answered their fire from the Place de la Madeleine, but could not enter into the street.

Alan Herbert now found himself in an exceptional, but uncomfortable, position, as witness of the struggle that ensued. As the regulars worked their way through the houses on his side of the street, the only point whence the Communards could fire back at them under cover was from the opposite corner of the street, immediately facing Herbert’s door. For the rest of the day Herbert watched, fascination and anxiety vying with each other:

The first who fired was a grey-headed, grey-bearded old man, who was the most bloodthirsty old fellow I ever saw. He hounded the others on, and had hot discussions, even with his own officers, so great was his determination to kill everyone he could see at the window, whether a soldier or not—so at least I interpreted through the bars of my prison. There were in all about twenty or thirty firing, and it was a horrible sight. They quarrelled as to who should have the most shots, whose turn it was to shoot, and from time to time one heard such expressions as these: ‘Oh, that caught him!’ It was just like boys rabbit-shooting. I do not believe, however, they

killed

many, but it would not have been possible to pass into the street, so hot was the firing. I was expecting every moment that one party or the other would endeavour to take possession of my house, but it was too much exposed to the firing. This fighting continued until night; no gas was lighted, and it was a very dark night, so we had a short respite.

At the Hôtel de Ville, something of the heat, confusion, and excitement of the March days had been recaptured. The Comité Central of the National Guard, the Artillery Committee, and all the various military services had concentrated there and were busy issuing

contradictory orders. Noisy, anxious suppliants besieged the Committee of Public Safety and the War Commission, while the Comité Central inveighed in every direction against the incompetence of different members of the Commune. Early that morning some twenty Communards gathered around the venerable figure of Félix Pyat, whose

Le Vengeur

had just emitted stirring cries of ‘

Aux armes!

’ It was very much Pyat’s moment. ‘Well my friends,’ he intoned in an heroically avuncular manner, ‘our last hour has come.’ It distressed him to see the ‘fair heads’ of so many young men around him; but ‘for me, what does it matter! My hair is white, my career is finished. What more glorious end could I hope for than to die on the barricades!’ To prove to posterity, that he Félix Pyat, had done his duty he now called for a roll-call of all those present. Then, in his familiar fashion, he disappeared. His white hair was not seen on any barricade—in fact, not seen again at all until Pyat turned up safely in exile in London; far from his career being ‘finished’, he survived to be amnestied and elected Senator of France sixteen years later.

In the midst of all this commotion, a delegation arrived from the Liberal-Democratic Congress in Lyons, which had come—via Versailles—with last-minute offers of mediation. They were hardly received with warmth. It was too late. Elsewhere in the Hôtel de Ville, Raoul Rigault was busy executing two orders of the Committee of Public Safety. One detailed him to implement the Decree on Hostages finally approved five days earlier; the second, dated ‘

4 Prairial

, An

79

’, called for the immediate transfer of the Archbishop and the other leading hostages from the Mazas Prison to the condemned cells at La Roquette. The actual transportation of the hostages he passed on to his deputy, da Costa, who requisitioned two goods carts—like the tumbrils of another age—for the operation.

As far as military instructions for the hard-pressed National Guards went, little of sense was being transmitted from the Hôtel de Ville. The Commune had anticipated that, when the Versailles attack began, it would be a frontal assault; not, as it developed, a series of turning movements which took elaborately prepared defensive positions and impromptu barricades alike from a flank, or from the rear, with depressing ease. There was a certain irony in the fact that the groundwork of Louis-Napoleon and his Prefect, Haussmann, was contributing as much to the reconquest of Paris as the planning of his old adversary, Adolphe Thiers. A co-ordinated, mobile defence would have been the only means of coping with these turning tactics. But the Commune no longer had a Rossel, nor even a Cluseret to dispose its forces; and in any case the National Guard was already showing an in-built, parochial reluctance to fight elsewhere than in defence of

its own district. So, just as the old Jacobins had fought until they were rounded up or slaughtered in 1848, Paris would be defended piecemeal and

ad lib.,

as it were—from barricade to barricade.

To those of its combatants with any military background, the total lack of direction from the Hôtel de Ville made the hopelessness of the situation abundantly plain. At about 10 o’clock on that night of May 22nd, some agitated National Guards brought Dombrowski into the Hôtel de Ville. Without a command since that morning, he had been seized while attempting—so it was claimed—to escape through the Prussian lines at St.-Ouen. Brought before the Committee of Public Safety, Dombrowksi vigorously denied that he had contemplated treason. The Committee ‘appeased him affectionately’; Dombrowski shook hands all round in an unmistakeable gesture of farewell, and strode off grimly towards the fighting. ‘There were’, wrote Lissagaray, ‘nights that were more clamorous, more streaked with lightning, more imposing, when the conflagration and the cannonade enveloped all Paris; but none penetrated more lugubriously into the soul.’

Yet despite the inertia and disarray of the Commune, already by the afternoon of the first day the main impetus of the Versailles attack had begun to slow down. In the Rue de la Paix, only a few hundred yards from where the front line was surging about Alan Herbert’s house, all Colonel Stanley had to report by lunchtime was that his friend, Austin, had been ‘slightly hit by a bullet, standing near the Louvre. A bit of shell killed a man this morning early on the Place Vendôme, and another bit fell in the yard of this hotel’. At 3 p.m. he added:

The line have got possession of the St. Lazare station, but they don’t seem to advance very fast. I heard a citizen remonstrate with a National Guard for uselessly breaking windows. A brute ordered me to help to work on the barricade. I told him to go to the devil and insisted on passing with my friend…. Two bodies of National Guards have passed round the corner and down to the Place Vendôme, poor devils, singing ‘

Mourir pour la Patrie

’. A perfect silence has happened since. I suppose the Line are entrenching themselves half across Paris. It is a funny state of things. Guns and musketry are beginning again. I was ordered off from my balcony just now. I keep a jealous eye on the bronze on the Place Vendôme,1 and shall take a bit as soon as the bother is over.’

At 10 p.m. that evening, he noted:

The National Guards are more cocky than ever. I suppose it is the wine they have had. [They] will insist on firing from the houses, which will entail retaliation. I have got a huge Union Jack hanging out of my balcony. Guns and musketry going on still, horses neighing and great talking; decidedly they mean to fight more.

The remnants of the friezes on the fallen column.

Stanley was not far wrong in his assessments. About the only advance that afternoon had been to capture the grounds of the British Embassy on the Rue St.-Honoré. And everywhere there were signs of resistance stiffening. In their scattered little packets, the Communards were beginning to fight as never before—the fight of despair. General Clinchant had anticipated that three days would suffice to occupy the whole of Paris, once the entry had been effected, but his calculations were upset by the degree of caution thrust upon the ‘liberating’ troops. Their leaders were concerned about rumours of whole streets being mined and booby-trapped; apprehensive (unnecessarily) as to the weight of artillery the enemy could bring to bear, by employing the cannon captured on March 18th; and mindful from their experiences of 1848 of what a toll could be exacted by desperate men fighting from behind barricades in the areas of Paris less friendly to the Government than Passy and the Étoile. They were still dubious, too, of just how much could be expected of the mixture of green young troops and defeated ex-prisoners of war under their command. Above all, Thiers remained determined that the work of repression should be carried out without haste, systematically and thoroughly. Announcing to a jubilant Versailles Assembly that evening that ‘the cause of justice, order, humanity, civilization has triumphed… The generals who conducted the entry into Paris are great men of war…’, Thiers added ominously, ‘Expiation will be complete. It will take place in the name of the law, by the law and within the law.’

In the final judgement of Paris that lay immediately ahead, it might be possible to perceive ‘order’; but remarkably little of justice, humanity, or civilization.

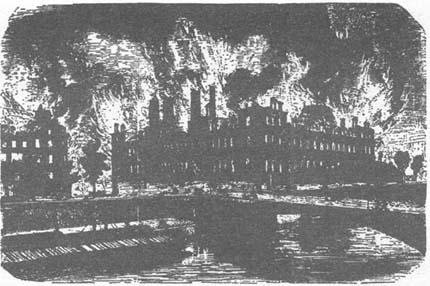

The Hôtel de Ville on Fire

25. ‘La Semaine Sanglante’—II

T

HE

dawn of Tuesday, the 23rd, broke on yet another ravishing May day. As the front had been stabilized the previous evening, it lay roughly along a north-south axis, running from the Gare des Batignolles in the north, through the Gare St.-Lazare, the British Embassy, the Palais de I’Industrie, across the Seine to the Chamber of Deputies, and up the Boulevard des Invalides to the Gare Montparnasse. Behind it, on the one side, the western third of Paris lay solidly in Government hands, behind it on the other, no less than five hundred barricades had been started in the respite provided by MacMahon’s slowing-down. But even before daybreak, his forces were on the move again. A short while later, Goncourt, still an involuntary ‘prisoner’ at his friend Burty’s house, climbed up to the belvedere to look out upon an ‘immense battle illuminated by the bright sunshine’. It was, he thought, ‘at Montmartre that the main weight of the action seemed to be concentrated’.