The Fields Beneath (32 page)

Read The Fields Beneath Online

Authors: Gillian Tindall

‘Town’ in a proper name in Old and Middle English does not indicate a town in the modern sense, but simply any form of inhabited place. When the ‘town’ has indeed been in existence since then, it is commonly found shortened to ‘ton’: until the nineteenth century one often finds ‘Kentishtown’ run together in one word or, earlier, even truncated to ‘Kentisston’. Perhaps its reversion to two separate words (with the modern emphasis on the latter one) was assisted by the establishment,

c.

1800, of Camden Town, a planned suburban development with its name invented by analogy with its older neighbour up the road. Within a few years of Camden Town’s establishment, Somers Town, and later Agar or Agar’s Town, similarly named after their ground landlords, made their appearance in the south of the old parish of St Pancras; and in Pentonville we have a Frenchified version of the same thing.

Various theories have been put forward to explain the Kentish part of the name. The most memorable, as well as the least probable, is the one repeated by Gillian Bebbington in her otherwise admirable book

London Street Names

. She states ‘Probably the first owner came from Kent’, and goes on ‘It is significant that the medieval manor of Kentish Town followed the ancient Kentish custom of gavelkind, whereby a dead man’s land was divided equally between all his sons and daughters and lots were drawn to decide the ownership of each.’ But the evidence for this in Kentish Town is sparse, and moreover had been rejected many times by other commentators. The truer, if duller derivation is probably from the common place-name particle ‘ken’ or ‘cain’, variously interpreted as a Celtic word for a green wood or a river. (I would also put up the suggestion of the Celtic

canto

, meaning border.) Following on this, a convincing theory is that Kentish is a corruption of ‘Ken-ditch’ – i.e. the ditch or watercourse of the Fleet. Some authorities have derived Ken from Caen in Normandy, and indeed that spelling of the particle was current for centuries in Ken Wood, the estate a couple of miles up the hill. Others, noting the similarity between ‘Kentish’ and ‘Ken Wood’ have concluded that the names are linked, and both possibly traceable to the same landlord. Ralph de Kantewood, who was Dean of St Paul’s after the Norman Conquest, seems to have owned both, and granted lands near St Pancras church to St Paul’s, from which time dates a long line of ecclesiastical ground landlords. But did Ralph de Kantewood give his name to the district, or did he in fact take his name from it? Lysons (

Environs of London

, 1796) managed to slide out of the issue by suggesting both possibilities at the same time, which does not make sense.

Lysons also seems to have been the person responsible for starting a rogue theory, which has gained wide currency, that ‘Kentish Town’ is a corruption of ‘Cantelupe Town’, after a Roger de Cantelupe who was prebendary of Kentish Town under St Paul’s in 1249. Certainly the manor whose lands covered much of the area came to be known as Cantelowes or Cantlers. But, as I have said, Ralph de Kantewood was on the scene almost two hundred years before the prosperous and powerful Cantelupe family, and the forms ‘Kentisshton’ and ‘Kentissetone’ crop up in documents that pre-date the Cantelupe ownership. No doubt it was mainly the coincidence of two rather similar-sounding names applied to the same district that gave rise to the belief that both were versions of the same common origin, but Lysons fuelled the confusion by interpolating the name ‘Cantelowes’ in parentheses into his translation of the entry for St Pancras in the Domesday Book. Subsequently later historians such as Samuel Palmer copied his translation but omitted the parentheses, thus making it seem as if ‘Cantelowes’ appeared in the original source. In this way are errors handed down from one writer to another, developing a persistent life of their own.

Nineteenth-century amateur historians seem to have had manor houses on the brain; they readily identified any and every large old house as ‘the old Manor House’ and frequently, for good measure, Bruges’s house as well, and these errors have been perpetuated. As I have stated in the text, Morgan’s Farm, the house built for Sir Thomas Hewett in the early seventeenth century on what later became the Christ Church Estate, was not a manor house, though nearly all the pictures in various collections that are labelled ‘Kentish Town Manor House’ or words to that effect depict this building. When they don’t, they depict another building with still less claim to the title: a stuccoed, single-gabled, apparently eighteenth-century gentleman’s residence situated in Willow Walk just behind what is now Fortess Road. (Under the bogus name of ‘Cantslow Manor’, it was demolished by the Metropolitan Board of Works for road-widening in the 1890s.)

It is virtually certain that both the St Pancras manor house and the Cantelowes manor house – mediaeval buildings which, by the time of the Commonwealth Survey in the mid-seventeenth century had declined into mere farms – stood much nearer to St Pancras Old Church than either of these spurious ones. I believe, in fact, that they were originally sited fairly near one another on opposite sides of the King’s Road (the present-day St Pancras Way). Those sufficiently addicted to historical detective work to wish to know

why

I believe this, are invited to read my article on the subject in the

Camden History Review IV

(Camden History Society publication, 1976). As an indication of the difficulty of interpreting disparate, fragmentary sources correctly, and the unwisdom of believing implicitly in any map of manorial holdings including the one in this book, I will confine myself here to pointing out that the usually scholarly and authoritative LCC

Survey of London

volumes contradict themselves on this point. Volume XIX confidently (and, I believe, correctly) plots Cantelowes Manor House on the west of the King’s Road, while Volume XVII states with equal confidence that it stood at roughly the same level on the eastern side of the road. Neither volume plots St Pancras Manor House at all.

(1977)

Standards of historical research have risen so much in the last twenty years or so that we seem to be living in a golden era of urban studies. The anatomy of the town is receiving an unprecedented amount of attention, and anyone working in this field today must acknowledge, as I do, a substantial general debt to forerunners like Sir John Summerson and Steen Eller Rasmussen. I also owe a great deal to more recent leaders in this field such as H. C. Dyos, Donald J. Olsen, J. T. Coppick, H. C. Prince, Peter Hall, and to the editors and writers of the recent Secker and Warburg

History of London

series.

I have other, more specific thanks to offer: first and foremost to John Richardson, Chairman of the Camden History Society, who has been more than generous with advice and help and with the loan of his own transcriptions from local manorial records and parish registers; also to other members of the History Society council, and particularly to Mrs Coral Howells for permission to use a letter written to her by Sir John Betjeman. Much gratitude also to the staff of the local history section of Camden Libraries, particularly to Malcolm Holmes, who has given me a great deal of incidental help. Also to Miss Joan Walton of Athlone Street Branch Library for her suggestions and interest. My thanks also to the staffs of the London Library, the London Museum Library, the Greater London Council Members’ and Picture Libraries, the Guildhall Library, and most especially to John Walford of the Public Record Office, who very kindly made original Census forms available to me when I protested to him on the difficulty of working from microfilm when comparing one decade with another. Also to P. C. Beddington, the Librarian of Gray’s Inn Library, for supplying me with information concerning the inglorious career of H. H. Pike.

So many people in the Kentish Town area have given me help of one kind or another that it would be invidious to mention names. My only regret is that I have not been able to use much more of what each of them has told me: inevitably, when working on a book of this type, one amasses a wealth of usable material which has to be reluctantly excluded for reasons of space. Particular thanks, however, to F. J. Napthine for allowing me to consult hitherto unpublished work of his own, and to Mrs Rose Deakin for supplying me with some figures relating to Census material.

I am grateful to Phillip French for several recondite suggestions concerning the appearance of my chosen area in literature; to Sir John Betjeman and his publishers, Messrs. John Murray, for permission to reprint his poem ‘Parliament Hill Fields’; to the publishers of the late T. S. Eliot, Messrs Faber, for permission to reprint seven lines from

East Coker

, and to Messrs. Macdonald and Jane for permission to reprint a passage from Compton MacKenzie’s

Sinister Street

.

Finally, very many thanks to Simon Jenkins, editor of the

Evening Standard

and author of

Landlords to London

, who read the manuscript for me and made a number of helpful comments, all of which I have tried to follow.

Gillian Tindall

1 From a print by Storer in the author’s collection.

2 and 3

Original watercolours in the Crosby Collection, Guildhall Library.

4 From a print in the author’s collection.

5 From the original in the Museum of London.

6, 7, 8 and 9

Extracted from maps in the possession of Camden Libraries’ Local History Collection.

10a Courtesy of Camden Libraries’ Local History Collection.

10b From an original in the Heal Collection, courtesy of Camden Libraries.

11a From the London Transport Collection, Camden Libraries.

11b Photograph by R. G. Lansdown.

12 From the London Transport Collection, Camden Libraries.

13a and b

Photograph by R. G. Lansdown.

14 From the London Transport Collection, Camden Libraries.

15 Courtesy of the GLC Picture Library.

16 Photograph by R. G. Lansdown.

In her long career, Gillian Tindall has written novels (one of which won the Somerset Maugham Award), two biographies, and a large number of short stories for print and radio, but she is now best known for her books of ‘micro-history’. Each of these takes a specific place, house or obscure group of people at a past date, and uses this to tell a story of much wider historical meaning. Her

Celestine, Voices from a French Village

has been paricularly aclaimed (and won her an honour from the French government) as has her

The House by the Thames

, but her first book of this kind was

The Fields Beneath

, first published in 1977 and in many subsequent editions. The area of London that it covers has been her home now for more than forty years, though she has a similar stake in a village in central France and also a long-term relationship with Bombay/Mumbai. She is married, with a son and grandsons.

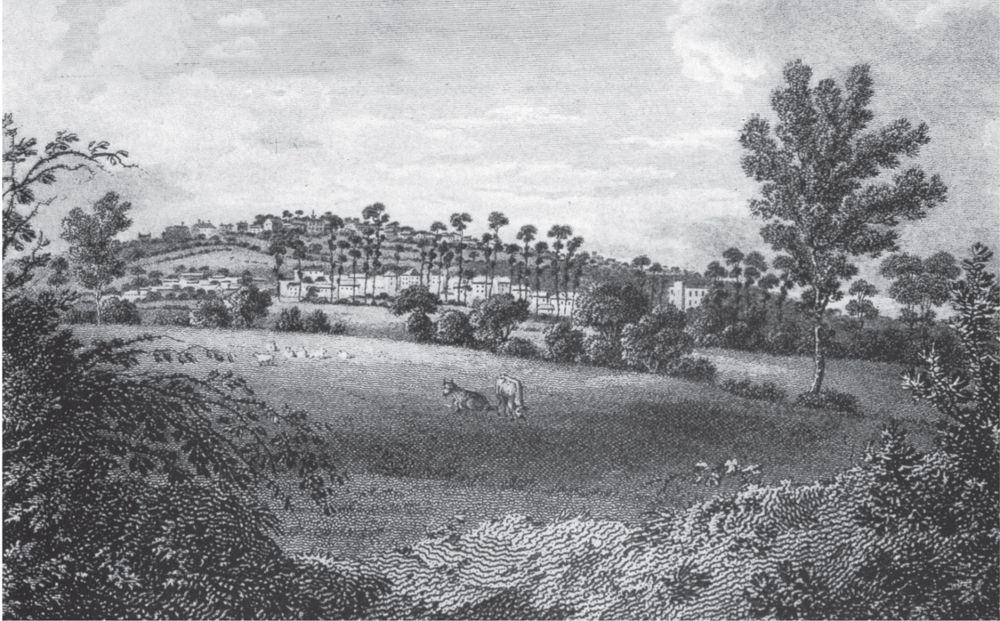

Kentish Town and Highgate beyond, viewed from the Chalk Farm area

c.

1800. It looks very rural, but in fact was already becoming a fashionable suburb.

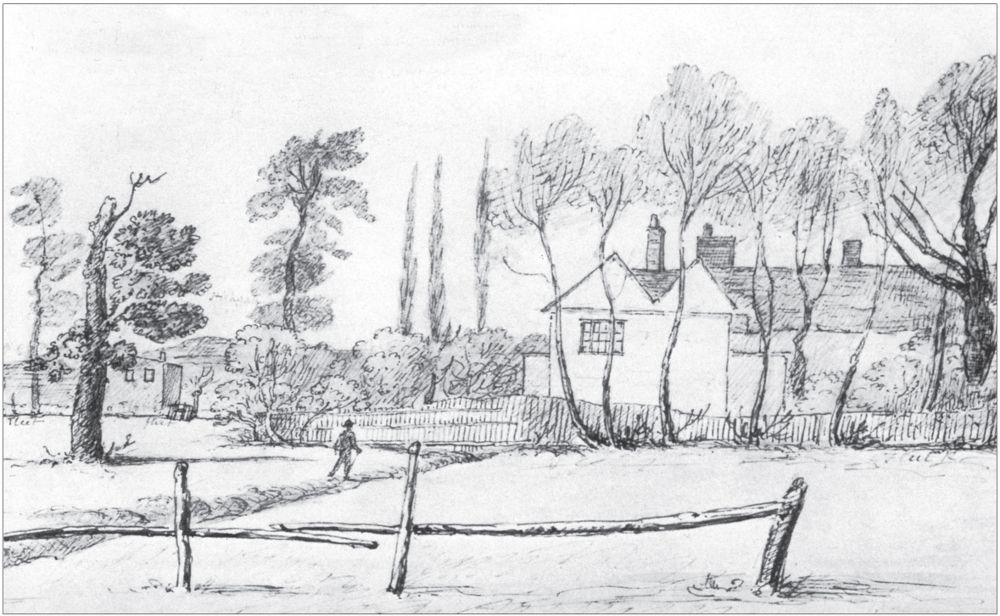

The Fleet, with a footbridge, at the back of the Castle Tavern,

c

. 1830. Within a few years, both fields and Fleet were to be covered over and the ancient tavern rebuilt as a ‘gin palace’. Today it has even lost its ancient name.

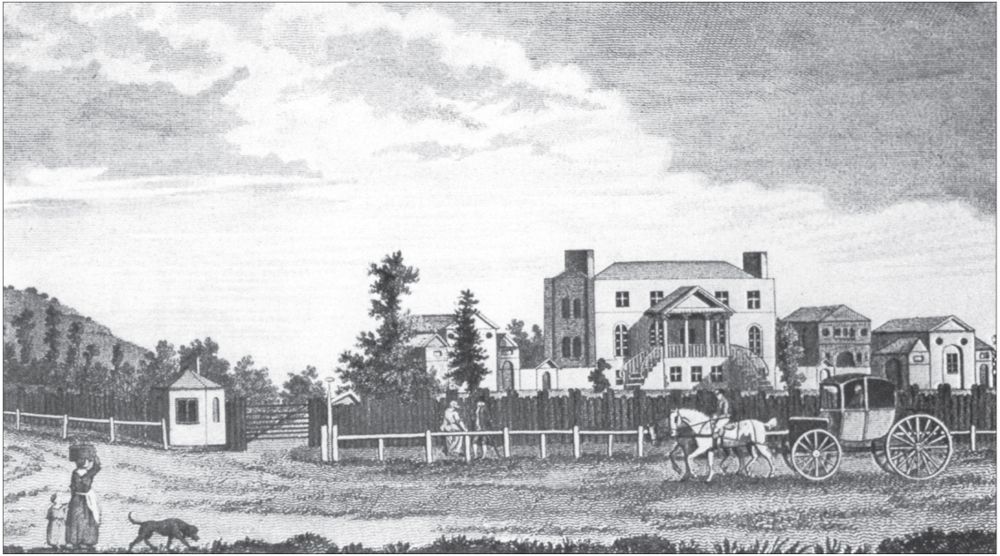

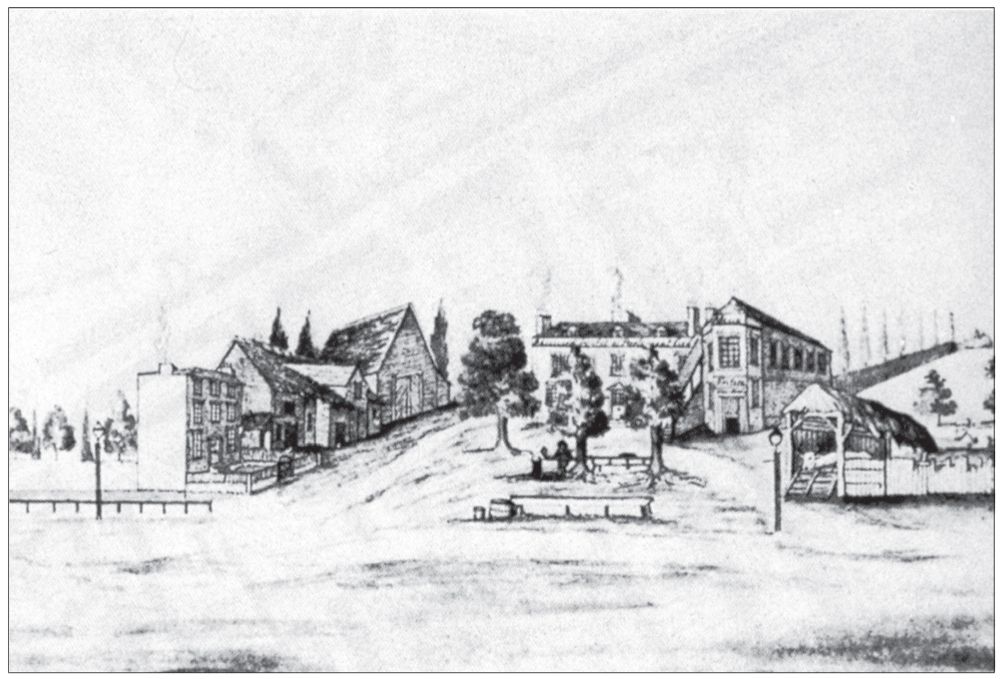

Hewitt’s fine Jacobean house, drawn in the early nineteenth century by which time it had descended the social scale to become Morgan’s Farm. The artist of both this and the preceding picture was a local man, A. Crosby, who fortunately was on hand to record the last years of Kentish Town’s countryside.

‘Bateman’s Folly’ at the foot of Highgate West Hill. By building it, complete with ornamental water gardens to the rear, its owner bankrupted himself. St Alban’s Road now occupies the site.

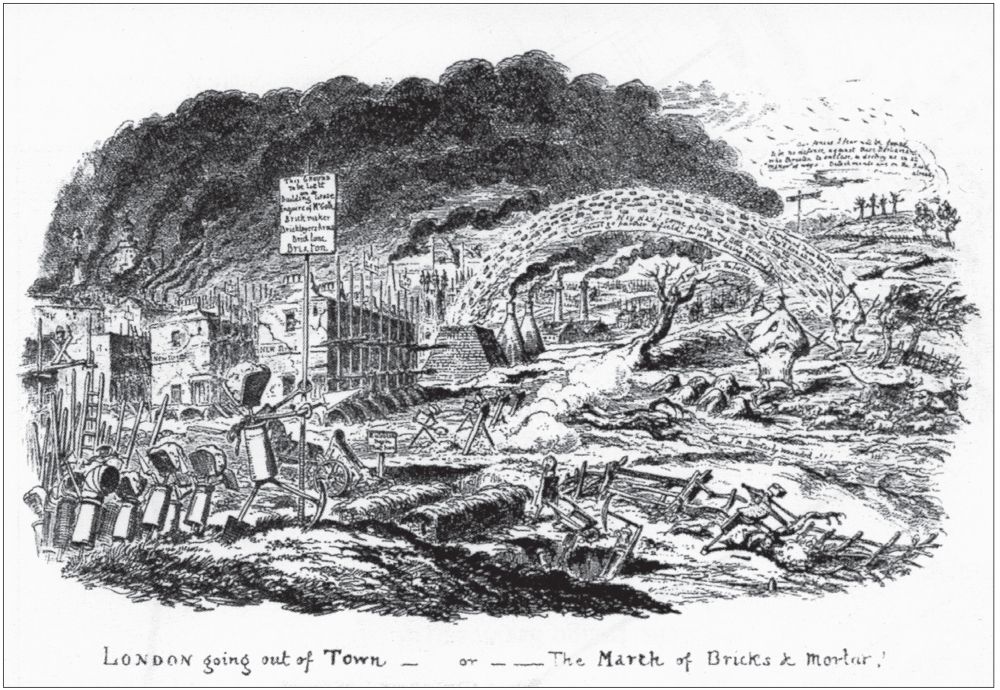

‘London going out of Town – or – The March of Bricks & Mortar’. Cruikshank’s famous cartoon about the nineteenth century growth of the metropolis, first published in 1829.

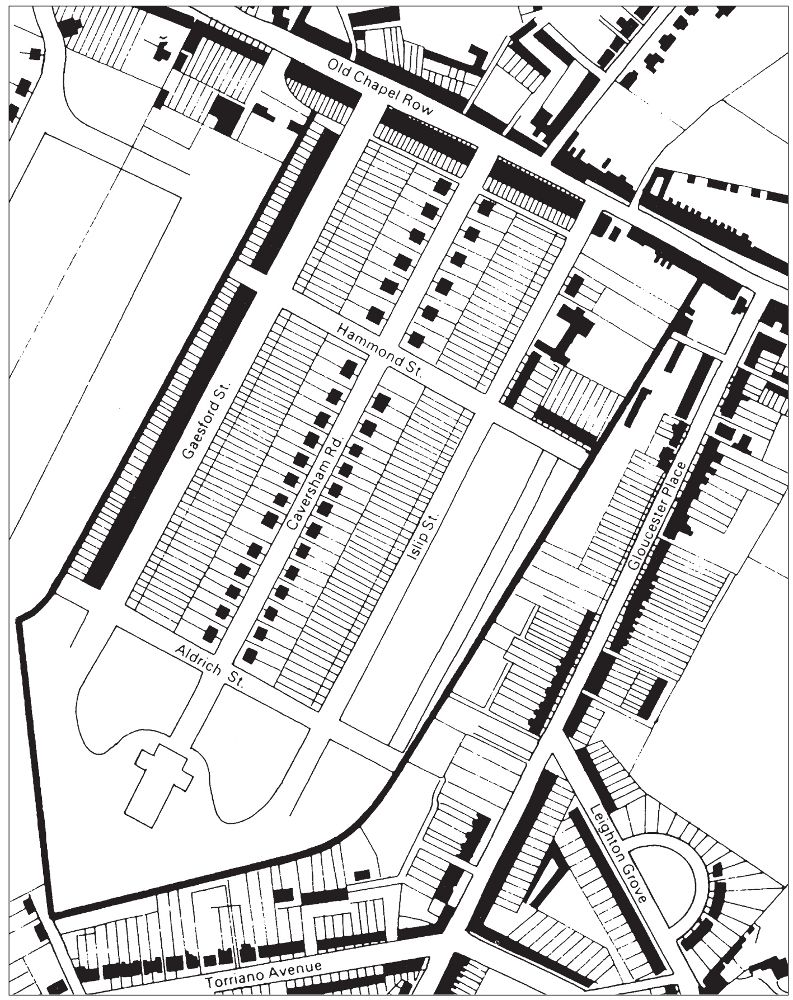

The Christchurch Estate (

in heavy outline

) – once Hewitt’s estate – in 1804.

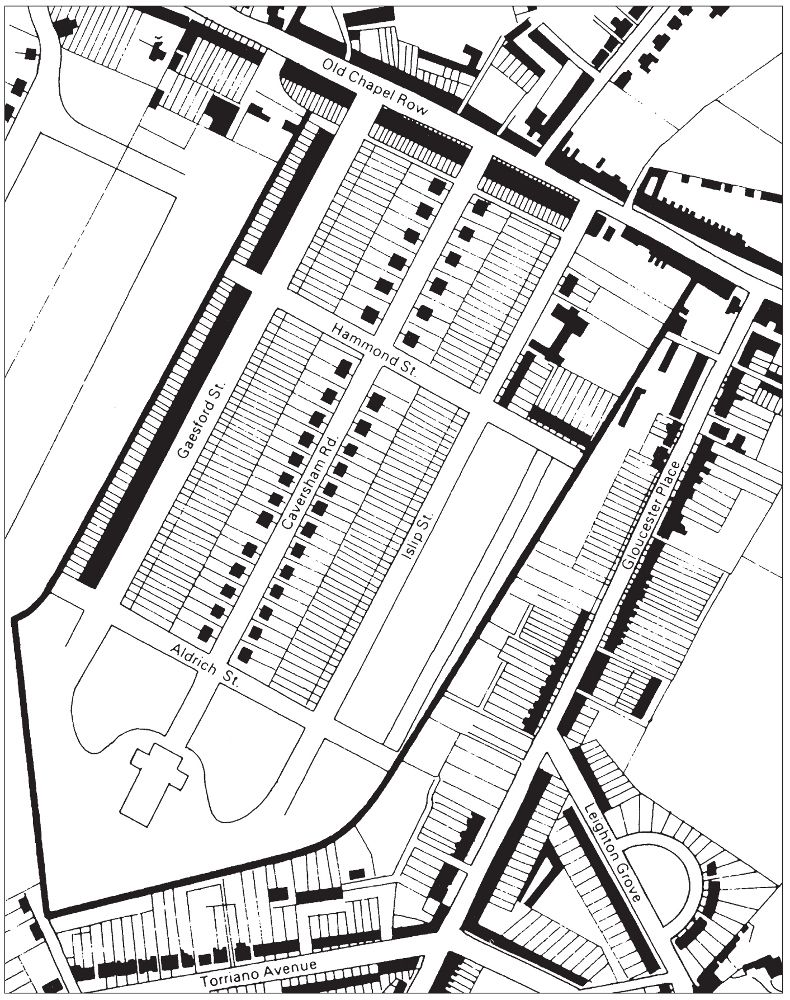

The Christchurch Estate (

in heavy outline

) – once Hewitt’s estate – in 1849. The remains of Hewitt’s house and moat are visible, not far from the high road.

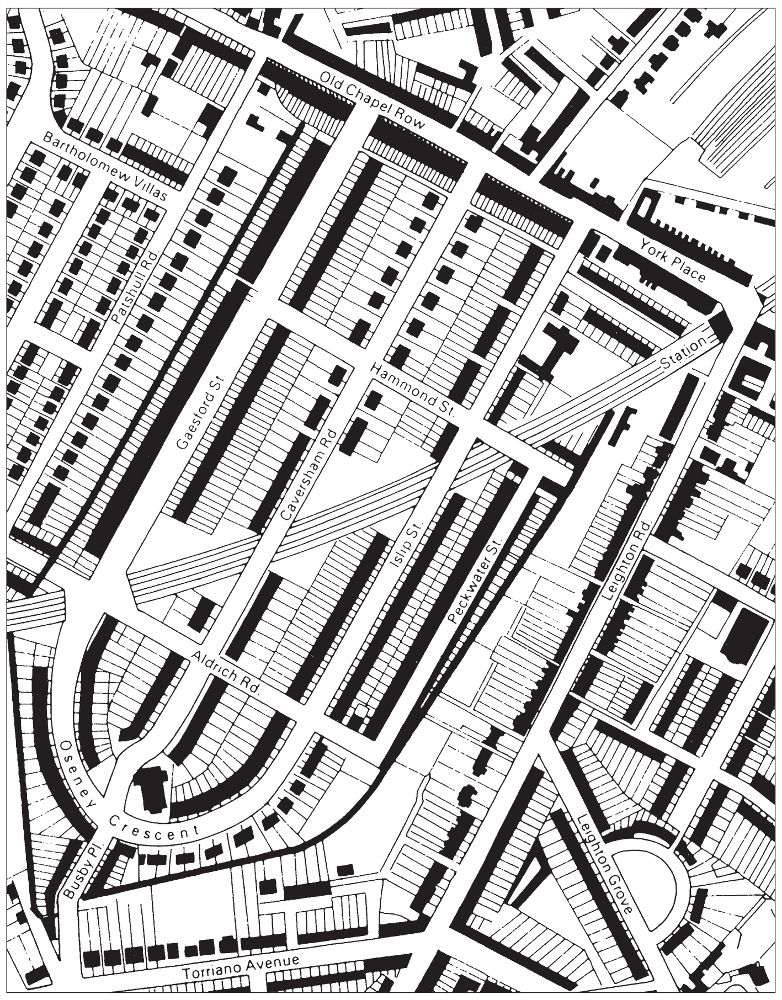

The development of the estate as projected in 1860.

The development of the estate as actually completed by 1880. Both plan and reality show the way in which the old field pattern became fossilised in the lines of the back garden walls, and affected the street plan particularly in the buildings of Oseney Crescent. What the planners of 1860 do not seem to have envisaged, however, is that the main Midland Railway would carry its line through the estate before the end of the decade.

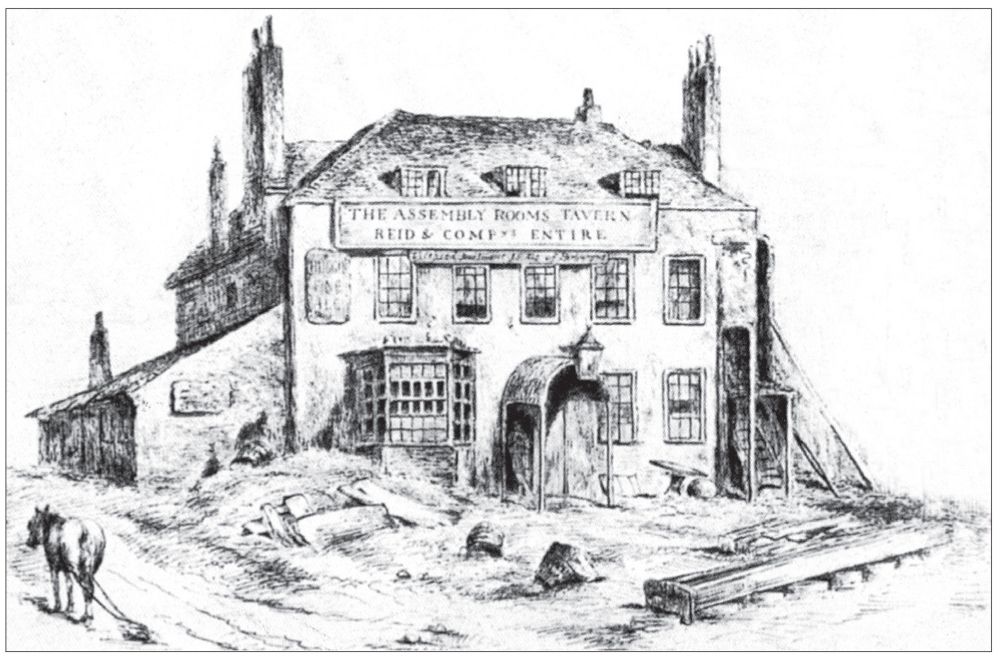

The old Assembly House tavern, where Leighton Road today joins Kentish Town High Street. A segment from King’s panorama of the district. Note Mr Wright’s oval table beneath the trees. Village House stands on the left.

The Assembly House just before being pulled down in 1853, after the collapse of the coach trade with the coming of railways. Note the oval table still in evidence.

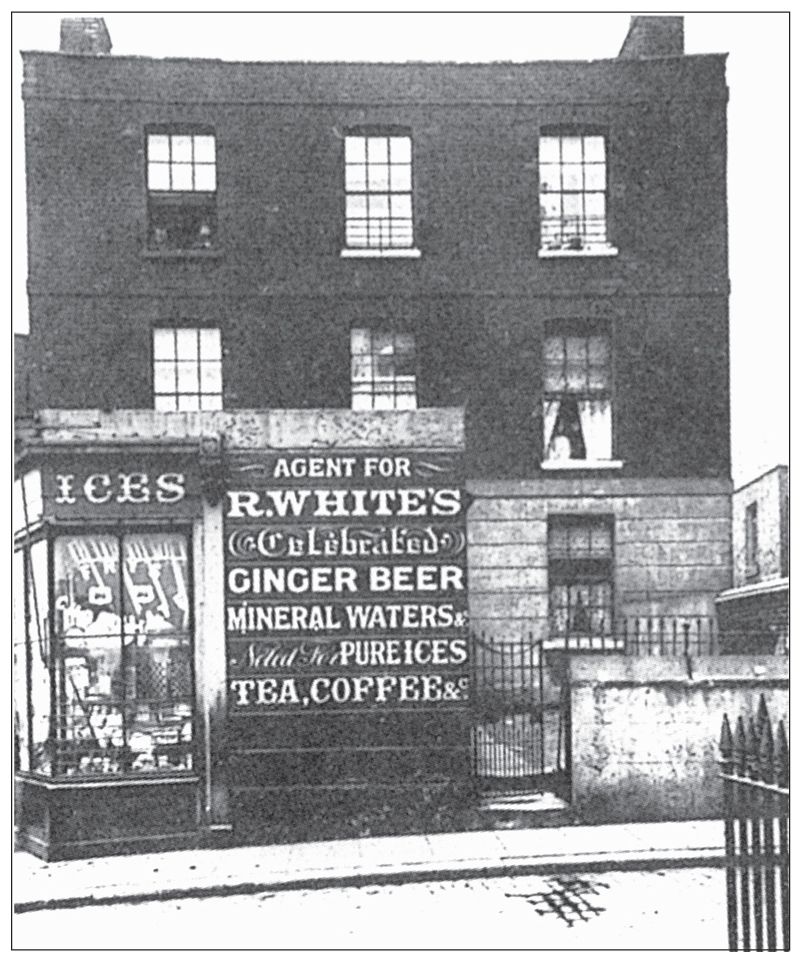

Village House, as was, c. 1900, with a shop built out in front of it but surviving, in a townscape where everything else, including the Assembly House, had been rebuilt and changed.