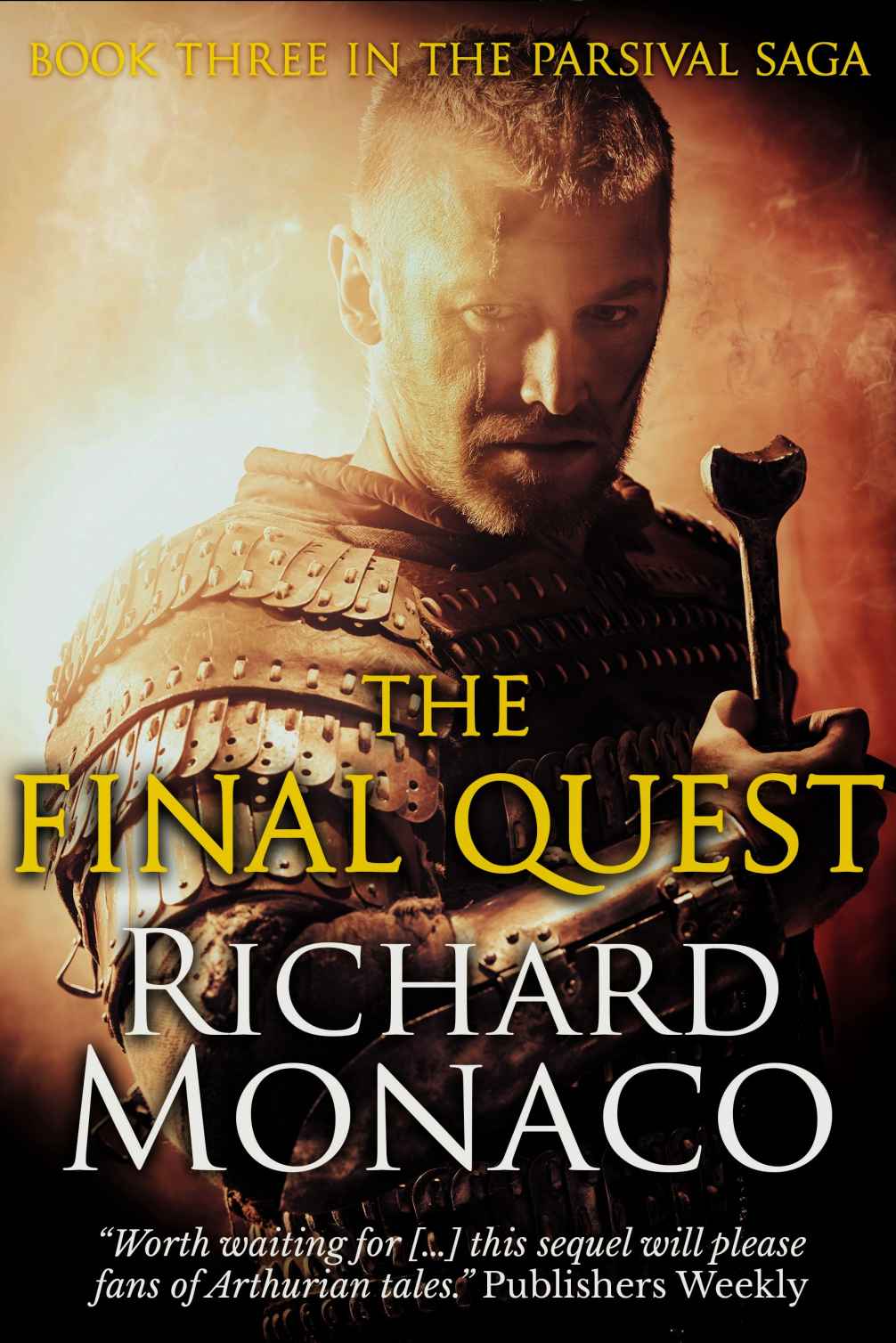

The Final Quest (The Parsival Saga Book 3)

Read The Final Quest (The Parsival Saga Book 3) Online

Authors: Richard Monaco

© Richard Monaco

Richard Monaco has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

First Published in 1982 by Sphere Books Limited

This edition published in 2016 by Venture Press, an imprint of Endeavour Press Ltd.

Parsival stood on the hilltop at dawn. The gray was brightening into a fuzz of pink in the east. The burnt-out forests below still smouldered right to the line where the flooding rains had finally checked the blaze.

He squatted and pondered the tracks in the muddy trail, but they told him nothing useful. Glanced again at the twisted body of the young man. Two sets of footprints passed over and around him. The mud had dried on his face. Like a mask.

He stood up and decided to follow the tracks. Passed the dead man (wondering how he came to be there, imagining it might make a tale in itself), then stepped over the black armored body: one of Clinschor’s killer knights, washed clean of last night’s blood, one arm dangling over the cliff edge. Paused, turned the man over and freed the great, fanged, faceplate. He’d never taken the trouble to look at one unmasked before.

A thrust had slipped through the eyeslit and ripped into the brain. The dark, dried blossom of blood took color as the sun lifted into a cloudless, shining morning. The cool air seemed to wash the world clean.

He stood up. Shook his head slightly.

Just

an

ordinary

dead

man

, he thought.

Only the mask was inhuman

. Stretched. Cracked his joints

. I’m nearly forty. I must have seen everything by now. Smiled. Well, I’m going back to the beginning again … I never seem to give up … Which way did my strange son go, I wonder? … I owe him so many years and that’s a debt can never be repaid, in truth … Which way? … not there, surely no one would go back to that …

He was looking over the blackened heap of countryside that filled the horizon: charred and crumbled trees, choked rivers, vanished towns, castles that were burnt-out shells … Turned and looked north: the trail ran across the hilltop, then curved down the slope, steeply, an ancient mortarless stone wall running beside it … vanished into the dense pine woods and rugged rock cliffs below and then, beyond, in the dawn haze, led into open, rolling country. Well, he couldn’t see where the trail came out, but he’d find a way through. He always did, he reflected. He’d never gone there before which made it a good choice. This was as far as he’d ever come. He’d been to these forests as a boy when he found the Grail Castle (which lay out of sight down the reverse slope) the first time. Then again, a day ago, fighting Clinschor’s men in the terrible storm … sliding down the long, muddy, steep hillside battling hand-to-hand with the ruined warlord … He hadn’t even bothered to go inside the castle this time because he knew the Grail was gone and believed he was free of it at last … well, perhaps he was … except he couldn’t really believe this hope or dream or truth that always had drawn him on was finished … he hated it too because his whole life seemed somehow to have been dimmed in a light that might not even have been real and he partly believed he’d lost his son because that image distracted and depressed and haunted all his days. Now he wanted his son back … he refused to think about anything else …

I’ll

go

where

I’ve

never

gone

, he thought.

There’s

as

fair

a

chance

he

went

that

way

as

any

other

.

The pathway was so steep in places that he had to hold one hand up to the stone wall as his feet skidded in the slick mud. He felt relaxed. Didn’t miss his sword. Didn’t think now because there was nothing to trouble himself with … rested his sight on the cool, stunningly bright forest below. The air was washed pure …

He was almost to the bottom of the jagged, cliff-seamed woods where the trails twisted and crisscrossed steeply. He stopped by a gleaming curve of metal. Stooped and picked up a helmet, ripped, battered, crusted with mud and dried blood. Turned it in a spray of sunbeams that penetrated the massed trees, saw the letter L elaborately worked in gold on the faceplate.

If

that’s

for

Lohengrin

, he thought,

then

once

more

I’m

wandering

as

if

I

traced

a

perfect

map

.

In

any

case

,

miracles

have

become

almost

ordinary

…

Tossed it aside into the dry brush and began picking his way down a rough cliff face beside a hissing, ringing thread of waterfall that twisted, spattered, and vanished into shadows, sparkled in spaced fragments where the leaves cleared and rocks pulled away and then finally lost itself somewhere in the softly rolling, grassy fields where the almost perfectly round hill ended. Flowed down like himself, he thought, only quicker … And smiled … and kept climbing down … and down … Gray hairs and blond catching the light …

Hot, noon summer sun. Baron Howtlande squatted beside the road, blinking sweat from his eyes, uncomfortable in his rusty chain mail shirt, wiping his bared behind with one stubby hand. Then, wiping the fingers on the resilient earth, he hitched up his leather pants, staring across the rolling fields of brush and scattered trees where the yellow dust road twisted and dipped. The light was a rich shimmer.

He moved a few steps along the grassy shoulder and squatted down again where shreds and bones of pig still crackled on the dying coals. He reached and pressed a seared rib to his sucking, surprisingly thin lips, tongue reveling in the sweet, hot fats.

He wiped his mouth into his reddish, grease-knotted beard. Squinted hard: he swore something had just moved again in the soft, honeylight-stained greenness. It was too soon, he reflected, for the raiding party to be coming back, and, anyway, it was the wrong direction … his men wouldn’t have gone south, to the barren country … so these might well be refugees from starvation and plague … yes … His stumpy limbs creaked him to his feet.

“Where’s Finlot?” he asked, chiseling a scrap of chewed gristle from his back teeth with a thick fingernail.

A skinny, short man with tight, incredibly detailed muscles and a blond beard had just come out of the underbrush.

“He went for water,” he said.

“I think we have travelers.” Gestured. The other squinted and shielded his eyes.

“There’s ten, at least, Howtlande.”

“Ah?” the bulky man was uneasy.

“Several are women and children,” the wiry man said. “You need not fear.”

“Ah …” Howtlande sucked his lower lip, thoughtfully. “Well, Skalwere, your Viking eyes are keen.”

“Why do men like you always say more than is needful?” “Eh?”

“It’s clear my eyes are sharp. Why talk about it?”

Howtlande grinned, sucking the end of the stripped bone again.

“Because,” he explained, “we’re civilized, unlike you northern dogs, and enjoy the pleasures of words. You’ve never been to a noble court, that’s plain.”

Skalwere spat.

“I prefer the pleasures of deeds, fat one,” he muttered.

“In that case, find Finlot and let’s hide ourselves. Mayhap these pilgrims yonder bear all their worldly treasure on their backs.”

For

, he thought

without wealth, I cannot bind enough men to me as will satisfy my purpose. In the end, I must have coin or fail.

“If their women be young that’s wealth enough,” Skalwere said, moving off through the green wall of bushes as Howtlande kicked dirt over the coals, never taking his eyes from the distant figures that wavered in the heat reflections as if they were images from lost worlds straining to take substance in the still, hot, golden afternoon.

Howtlande moved behind the screen of leaves and squatted in the cool shadows. Belched and relaxed … half-heard birds quarreling in the dense branches overhead … mulled over his plans. At first, survival had been enough. He preferred not to think about the past, but the final days of the war for the Grail haunted him and leaked into his dreams still. Survival had been a rare luxury for a time. Everything had gone wrong: the fire they’d set to raze what they didn’t want to hold had trapped and destroyed their own army as well as the crumbling Briton opposition, and in a matter of hours he’d become a general commanding only his own hide, crawling down the muddy mountainside through a raging storm and struggling on through the charred countryside where tens of thousands of soldiers lay heaped in fragile ash shapes, sealed together in melted armor. Moving on past what in the moonlight he took for unending rows of them blurred by the flooding and darkness. He had gone mad for a time (though he blanked that out): he’d felt them all following him, rolling over the earth in a tide of shadows, and he’d fled, pale, frantic, choking on the bitter ashes, flinging away most of his armor and finally, towards dawn, blacking out … waking in the pallid sun just outside the vast line of desolation, his body smeared, mouth and nostrils half-plugged with soot and muck … wandering in staggers over the still wet, green ground, then dropping into a tepid, muddy stream and cleaning himself as best he could, rinsing his mouth with foul water that had flowed from the heart of the ruined country.

He peered through a break in the leaves and watched them coming. One was riding either a pony or a mule. The heat shimmers still shook and bent the forms severely.

Men

and

gold

, he thought,

gold

and

men

… There were more survivors than he’d expected. They kept turning up.

A slight stir in the undergrowth told him that Skalwere and probably Finlot were getting into position.

I

left

Germany

a

lord

and

I’ll

not

return

a

beggar

, he reflected once again. It was one of his favorite thoughts. The bitterness of it was a consolation

. Lord master was a fool I’m not a fool. There’s all the logic I’ll ever need … My dreams stay in my sleep where they’re harmless. What I see I see … even if you suffer from seeing devils, if you know they’re made of nothing then you draw the teeth of madness

… Nodded self-agreement.

That was his error: the stinking Grail dream … It caught all of them and ruined all of them …

Shook his head, thinking of the armies and immense wealth that had been spilt and lost.

“Fanatics,” he muttered. Stood up behind the screen of glistening leaves floating in the bright, hot, droning afternoon as the party, in traveling capes and peasant clothes, came around the near curve of road. The scraggle-faced man mounted on the dusty mule looked, Howtlande thought, vaguely like a priest, though he wore no cross or beads.

He counted thirteen of them. Then stepped out to bar their way, noting that only two had weapons visible: the rider had a short sword, and a gray-haired, massive fellow in weathered hides rested a spear over his shoulder. A hooded woman and two children stood close to the armed peasant. The dust blended everyone together.

Howtlande noticed how the

middle

-

aged

man

stopped

alertly

and

looked

(

instead

of

at

him

)

left

and

right

.

This

, he thought,

was the one to watch.

“Who blocks our course?” the rider demanded in a thin, violent voice.

“Say rather, ‘my lord baron,’ you ass on an ass,” Howtlande suggested.

“You’re a nobleman?”

“You say true, ass.”

“Few are met with in these days,” the man said. He seemed to be spokesman for the group that watched and waited, uneasy, silent.

“Well,” Howtlande answered, “you’ve met with one. And he waits for you to pay the toll.”

The rider was scornful.

“Pay what?” he said.

“The road toll.”

“Hah. You do better to join us. There’s nothing at your back but trees, I think.”

“The rate goes up apace,” Howtlande said.

“I serve a great leader,” the man said, “who is gathering the country together again. We always can favor a fresh sword.”

“A great leader.” Howtlande was smiling, quite relaxed now. Kept watching the big man with the spear, who was a little apart from the others as if he’d been following along without commitment. “These are troops, then?” He indicated the ragtag peasants.

“Follow us and bear your own witness.” the man’s face was very red around the eyes.

“Who’s this great leader? Lord who?”

“The golden eagle, he’s called.”

Howtlande guffawed. Spat and wiped his greasy lips with the back of his hand.

“Ah,” he said, grinned, as Skalwere and Finlot (a bleak-looking, wintery-eyed, long man) stepped out of the cover on either side of the road. He noted the massive man seemed unsurprised. Had expected that. “More like the golden asshole.” Drew and pointed with his sword. “Leave the women and your purses.” Smiled. “Even that fat one. Skalwere likes to harpoon blubber like a true Norseman.”

Only Finlot seemed remotely amused.

“That’s good,” he said.

“That’s the toll,” Howtlande continued. “You may as well pay and ride on.”

“You fools!” exploded the violent, flat voice. “Mere brigands. I offer you —”

Howtlande hit him alongside the head with the flat of his blade, moving with remarkable celerity. Watched him flop into the ditch.

“And the mule too,” he said.

The rest were already moving, most bolting, the fat woman (he noticed peripherally) hesitating, looking from Finlot to Skalwere as if to see which were the Norseman, he thought, amused, as he sliced the leg from under a fleeing teenager and left him screaming and twisting in the dust, as the other two ripped into the rest, hacking, stabbing and tripping and herding the women together at the same time. A young peasant pushed Skalwere away from a girl and Finlot jabbed his spear between his ribs and dropped him to his knees in the dust, thick, dark blood flooding from his mouth. Howtlande gripped the mule’s reins now, watching the massive man with the long spear backing to the underbrush with the hooded woman and two children. One girl and a couple of peasants had broken away and were scrambling into the trees. He’d never expected to take them all but they’d done quite well for three men, he decided. Soothed the mule, absently, watching Finlot trip a woman who tried to get up, using the butt of his spear as Skalwere smashed another in the temple, knocking her flat in the ditch, and then turned and plunged after the spearman and family, leaves rasping, branches snapping, as he vanished into the brush. Howtlande, still soothing the mule, stood over the rest with Finlot.

Skalwere was surprised not to find them instantly and trotted and struggled deeper into the greenrich, sunshook tangles, tripping on roots, ripping a path with his sword, slapping stiff, barbed branches from his eyes … stopped and listened … wasn’t sure if he heard movement or not … voices floated vague and muffled from the road behind him.

“They move like Picts,” he muttered to himself.

And then he turned, surprised, as the big man appeared behind him and his body ducked and twisted to miss the vicious thrust. Then he squatted down, grinning.

“Ah,” he said, “you be no common Briton.” Waited for the man to take advantage and charge, ready to roll under the spear, close and kill. Except the massive, iron-gray bearded fellow (whose eyes, he noticed, were bright blue chips in a nest of squinting) moved forward one easy, patient step after another, spear cocked just enough, held just high enough. Skalwere appreciated this and began hunkering backwards into the screening berry bushes, shaking the faint threads of sunlight. He decided there was no point in empty risks what with solid booty waiting. There would always be another day. There always was, he reflected. Paths, he thought, always crossed in those narrow times. After a few yards he stood up and began working his way back to the road. Everything was quiet there now except for a shrill weeping that he assumed was a woman or a hurt lad. All around the birds took up their chirping again.

As Broaditch moved quietly the few steps to the thick tree where Alienor and the children crouched, he gestured with the spear and all silently and quickly went on through the tangles, finally coming out, farther back, into a rolling field of dried grasses and tuftlike clumps of brush and spread-out lines of coppery cypress that seemed to flicker up into powdery sky, like flames.

“Well,” he said, at length, leading them on in a wide circle that he reckoned would bring them back to the valley road a mile or so beyond the raiders. “We’ve become wild creatures enough. All of us.”

Alienor had pulled back her hood. Red-gray hair glistened in the steady, heavy sun.

“Water flows, husband,” she said, “the nearest way it can.”

“Well, it don’t please me, woman,” he answered, “put it any way you like.”

“How far is it, father?” the girl, Tikla, wanted to know. She was keeping pace with her slightly older brother, who was whipping a willow switch at tall, stooped sunflowers as he walked.

“I would restore to them,” Broaditch said, peering alertly around, “their lost childhood … Aye … and my own lost everything else too, had I the power.”

“Father?” she repeated.

“Not far, child.” Frowned and murmured. “No more than eternity away.”

“Your father,” Alienor put in, “has come to riddling like a mystic hermit since we found him.”

“It was this hermit, woman, did the finding.”

“Oh?”

“Aye. Right enough. And were not easy as finding shit in a cowbarn.”

“A sweet comparison.”

“Well, just, anyway.”

“Oh? And were we not where we were when you come upon us you’d not have found us.”

He frowned and smiled and shook his head as if struck.