The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (39 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Whether or not ER understood the dynamics of within-group color prejudice, the story fascinated her. “

If the rest of your book flows as smoothly,” she said, “you are sure to have success with it.”

As Murray’s attachment to ER grew stronger, she increasingly spoke of the familial bond she felt. “

Did I ever tell you,” Murray boasted, “I was christened

Anna

Pauline, a first name that carries with it a very high standard to meet—two high standards, in fact.” The standard-bearers to whom Murray was referring were her paternal grandmother,

Annie Price Murray, and ER, whose first name was also Anna.

PART VII

FIGHTING FOR A JUST WORLD,

1956–59

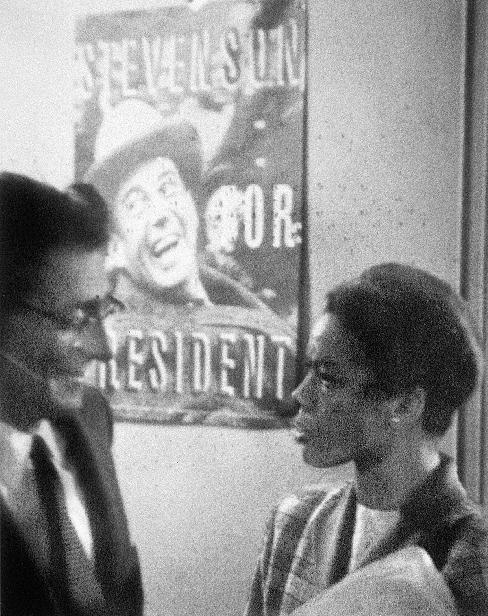

Pauli Murray (right) confers with an unidentified supporter at an Adlai Stevenson campaign event, New York City, 1956. “Civil rights cannot be dealt with with moderate feelings. It involves a passion for justice and for human decency, and if Mr. Stevenson has not felt this passion, then he does not belong in the White House,” Murray told the columnist Doris Fleeson, who was a Stevenson loyalist.

(The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, and the Estate of Pauli Murray)

43

“There Appears to Be a Cleavage”

B

y February

1956, the presidential campaign was in full swing, and Eleanor Roosevelt was backing Adlai Stevenson’s second bid for the Democratic nomination. Pauli Murray had endorsed the governor

in 1952. She was inclined to support him again. However, his cautious response to the

Brown

decision and the

Supreme Court’s subsequent rulings in a number of desegregation cases gave her pause.

If enforced,

Brown

promised to transform social relations in the South, and the reaction of

segregationists was predictably hostile.

The general assembly of the Commonwealth of

Virginia moved to provide state funding for private schools.

Louisiana legislators passed a law that banned the state’s athletic teams from playing opponents whose rosters included African Americans. Authorities across the South posted fresh “White Only” and “Colored Only” signs at

bus and

railroad stations, boldly defying the

Interstate Commerce Commission’s ban on segregated interstate transportation.

Mississippi governor

James P. Coleman threatened to close the state’s colleges rather than admit black students. He was not alone in his resolve.

On March 12, Georgia senator Walter F. George took to the Senate floor and read a manifesto opposing racial integration on behalf of some one hundred

southern members of

Congress. The

Brown

ruling, George and his colleagues argued in their statement, was “

a clear abuse of judicial power” and an encroachment on

states’

rights. Although they publicly advised against “disorder and lawless acts,” their vow “to use all lawful means” to reverse

Brown

and to “prevent the use of force in its implementation” emboldened those intent on disobeying the high court through violent measures.

It was ironic that Murray happened to be

writing a chapter on

Reconstruction in her memoir. The “

parallels” between that tumultuous period after emancipation and the current backlash against integration pained her. Tears spurted from her eyes onto the

typewriter as she chronicled the quest of former

slaves for full citizenship and the furor of whites determined to stop them.

“

Proud Shoes

is every much a story

of 1956 as it is of 1866,” she told Corienne

Morrow. When Eleanor Roosevelt read Murray’s chapter draft, she too found the similarities “

sad but true.”

· · ·

VEHEMENT OPPOSITION TO INTEGRATION

made wooing southern conservatives without alienating blacks and

liberals an impossible task for

Stevenson. As governor of Illinois and as the

Democratic presidential candidate in 1952, he had established solid liberal credentials. But he stunned many of his allies when he did not speak out after the August 28, 1955, murder of

Emmett Louis Till, a fourteen-year-old black boy accused of flirting with a white woman in Money, Mississippi. Matters worsened after Stevenson told a gathering of black leaders at the

Watkins Hotel in Los Angeles that he wanted “

to proceed gradually” with integration so as not to “upset the habits or traditions of generations overnight.”

Thus, he would not enforce the law with troops and set off another civil war.

The governor’s relations with African Americans suffered another setback when he declined to endorse the

Powell amendment. This measure, proposed by a fiery black congressman from New York City, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., denied funds to states with segregated schools.

Incensed by Stevenson’s remarks,

Roy Wilkins, who had succeeded

Walter White as chief executive of the

NAACP, lashed out at a birthday observance for

Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois. “

To Negro Americans ‘gradual’ meant either no progress at all,” Wilkins argued, “or progress so slow as to be barely perceptible.”

George Meany, president of the powerful American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, was irritated too, and he accused Stevenson of “

running away” from the

Brown

decision.

As the Democratic Party’s left wing pulled away from Stevenson, ER found herself in the unenviable role of go-between. She regretted his remarks in Los Angeles; even so, she thought black activists and the press had overreacted.

Eager to de-escalate tensions, she issued a statement from the governor’s Chicago campaign headquarters, imploring people to consider the evidence. “

The record,” she offered, “should speak more loudly than words because it was created not only by words but by deeds.” She told civil rights leaders that she agreed with the governor’s concern about changing “

mores faster than people can accept it.”

To Murray, Stevenson’s remarks and

ER’s defense of him signaled that civil rights had become “

secondary to winning the White House.” Murray registered her disappointment in a letter on February 16, 1956.

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt,

…There appears to be a cleavage in your point of view and that of Negro leaders whom you have known and worked with over many years in harmonious relations and fundamental agreement. This difference may be more fundamental than you realize. If so, it would be tragic for all of us. You have also indicated your perplexity at the present confusion and misunderstanding surrounding Mr. Stevenson’s statement. Because I fear further misunderstanding among people whom I am sure are in agreement on principle, I urge you at your earliest possible free moment to counsel informally with leaders in this field whose opinions you respect and in whom you have trust and confidence.

Among those Murray recommended ER consult were

Ralph Bunche, Lester

Granger,

Frank Horne, Maida

Springer,

Channing Tobias, and

Robert Weaver. Murray excluded herself on the grounds that she had no “

close association with public leadership” and, therefore, had “no place in such a discussion.” She did offer to help, if asked.

It is somewhat curious that Murray disqualified herself from the discussion, given her admiration for Stevenson, her strong opinions about his campaign, and her extensive background in civil rights. This decision, perhaps, recognized the difficulties she experienced working in groups, her bumpy relationships with male civil rights leaders, and her desire not to attract further attention from the

FBI.

ER offered her opinion of these matters a week later.

February 22, 1956

My dear Pauli:

I had a long talk with Ralph Bunche yesterday and I don’t think that fundamentally there is any cleavage between my point of view and that of Mr. Stevenson and that of the really wise Negro leaders. I did not like Roy Wilkins’ hotheaded statement which I thought poorly thought out, nor did I like the garbled reporting of what Mr. Stevenson said in Los Angeles. Unwittingly Mr. Stevenson used the word “gradual” and this means one thing to the Negroes but to him it was entirely different. However, Mr. Stevenson’s record remains remarkably good and he certainly was courageous in the statements he made in the last campaign. I think so far he has made no really deeply felt statement on the situation but I don’t think that is because of any political reactions that might come. I simply think that he is waiting for the time when he thinks it will be of most value. However, the more he seems to be under attack by the Negroes, the less possible it is for him to make such a speech because he will be accused of doing so in order to get the Negro vote.

The only thing on which Stevenson and I differ with some of the Negro leaders is in the support of the Powell amendment. His feeling is that aid should not be withheld from the states that need education most in order to improve. He also realizes there are many other ways, probably more effective, which can be used to influence the South on desegregation of schools if you have the money. It seems to me obvious that if a state was flouting the Supreme Court or if it passed legislation to make all its schools private, it could not receive money, but if it is within the power of the Executive to allocate it, he could use that to influence the recalcitrant Southern states.

I have just come back from a trip to Florida, Georgia and South Carolina and I don’t think that putting children in a classroom together is all that has to happen. Many things have to be improved—housing, economic conditions, and the right to vote and protection in that right. It will probably take a generation or so before a colored child can hope to be receiving equal education even if long before that time it sits in the same schoolroom. In the meantime, if the Powell amendment gets through in the House, the Republicans will call the bill up in the Senate, immediately the Southern Senators will filibuster and no other bill will come through. The Republicans will then say: “Look at the Democratically controlled Congress which did nothing.” Truman used that very effectively in the last campaign.

I think it is a mistake for the Negro leaders to be tearing down Stevenson who is after all the only real hope they have, the President having told Mr. Powell that he would make no statement on whether the Executive would refrain from allocating funds where schools were segregated. Yet the papers and the Negro leaders have not attacked the President. Why this discrimination?

I think the courage being shown by the [Aubrey and Anita] Williams and the [Clifford and Virginia] Durrs and people like them in Alabama just at the present time is really something quite extraordinary and I hope it will get recognition and praise from the Negro leaders, though I would not like the praise to be voiced just now because I think it would make life harder for the courageous Southerners.

Affectionately,

Eleanor Roosevelt

Neither ER’s testy defense of Stevenson nor her warm closing swayed Murray. She still wanted a forceful, unambiguous endorsement of

Brown

and the principle of racial integration from the governor. Of her disagreement with ER about Stevenson’s position, Murray confided to Corienne Morrow, “

Much as I love and admire her, I have never for one moment been under illusions as to the limits of her extension of herself on these issues. She has reached her hand across the line as far as any human being can do—considering her political commitments.” Murray observed, “

She is a regular Democrat, and as fond as she is of me, I shall never forget her article in…

Ebony

, entitled

‘Some of My Best Friends Are Negroes’ (the editor’s title, not hers) in which she characterized me as a

‘firebrand’ (which I am and proud of it) and that I had done some ‘foolish’ things in my youth (which I did, but not the ones to which she was referring).”

· · ·

BY THE SPRING OF

1956, Murray had nearly finished the

memoir. She also learned that the

New York City Commission on Intergroup Relations had hired

Morrow as a research associate. (Her old boss

Frank Horne had been named executive director.) Murray credited her own perseverance and Morrow’s good job fortune in part to

ER’s “

encouragement and understanding.” In spite of an unwieldy schedule and innumerable personal commitments, ER had diligently responded to Murray’s drafts and generously recommended Morrow to Mayor Robert

F. Wagner Jr. for the commission post.

Just as Murray began the final revision, doctors diagnosed her last maternal aunt, seventy-nine-year-old Sallie F. Small, with advanced liver cancer. It had been less than six months since

Aunt Pauline’s death. Murray was awash in “

troubles.”

The strain of another loss on Murray worried ER, and she invited Murray to

Val-Kill for an overnight stay. Unfortunately, Aunt Sallie took a turn for the worse, and Murray missed the appointment. The mix-up was “

providential,” she later wrote to ER, as her aunt passed on May 19, the day she was to come to Hyde Park.