The First 90 Days (45 page)

Authors: Michael Watkins

Tags: #Success in business, #Business & Economics, #Decision-Making & Problem Solving, #Management, #Leadership, #Executive ability, #Structural Adjustment, #Strategic planning

Chapter 7: Build Your Team

Overview

When Liam Geffen was appointed to lead a troubled unit of an instrumentation company, he knew he was in for an uphill climb. The extent of the challenge became clearer when he read the previous year’s performance evaluations for his new team. Everyone was either outstanding or marginal; there was nobody in between. Clearly, his predecessor had played favorites.

Conversations with his new direct reports confirmed Liam’s suspicion that the performance evaluations were skewed.

In particular, the head of marketing seemed reasonably competent but by no means a minor god. Unfortunately, he believed his own press. The head of sales struck Liam as a solid performer who had been blamed for poor judgment calls by Liam’s predecessor. The relationship between marketing and sales was understandably tense.

Liam recognized that one or both would probably have to go. He met with them separately and bluntly told them how he viewed their performance ratings. He then laid out detailed two-month plans for each. Meanwhile he and his VP for human resources quietly launched a search for a new head of marketing. Liam also held skip-level meetings with midlevel people in sales, both to assess the depth of talent and to look for promising candidates for the top job.

By the end of his third month, Liam had signaled the head of marketing that he would not make it; he soon left.

Meanwhile, the head of sales had risen to Liam’s challenge. Liam gave her more opportunities, eliciting even better performance. Eventually Liam had enough confidence in her to give her overall responsibility for sales and marketing.

Liam Geffen recognized that he couldn’t afford to have the wrong people on his team. If, like him, you inherit a group of direct reports, it is essential to

build your team

to marshal the talent you need to achieve superior results. The most important decisions you make in your first 90 days will probably be about the people on your team. If you succeed in creating a high-performance team, you can exert tremendous leverage in value creation. If not, you will face severe difficulties, for no leader can hope to achieve much alone. Bad early personnel choices will almost certainly haunt you.

As one experienced manager put it, “Hire in haste, repent at leisure.”

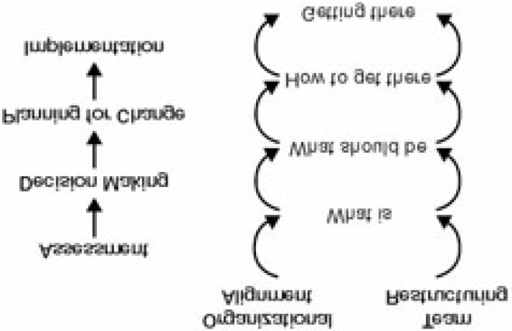

Finding the right people is essential, but it is not enough. Begin by assessing existing team members to decide who will stay and who will have to go. Then devise a plan for getting new people and moving the people you retain into the right positions—without doing too much damage to short-term performance in the process. Even this is not enough: You still need to put in place goals, incentives, and performance measures that will propel your team in the desired directions. Finally, you must establish new processes to promote teamwork. This chapter will walk you through these steps.

This document was created by an unregistered ChmMagic, please go to http://www.bisenter.com to register it. Thanks

.

Avoiding Common Traps

Many new leaders stumble when it comes to building a winning team. The result may be a significant delay in reaching the breakeven point, or it may be outright derailment. These are some of the characteristic traps into which they fall:

Keeping the existing team too long.

Some leaders clean house too precipitously, but it is more common to keep people longer than is wise. Whether because of hubris (“These people have not performed well because they lacked a leader like me”) or because they shy away from tough personnel calls, leaders end up with less-than-outstanding teams. This means they will either have to shoulder more of the load themselves or fall short of their goals. One experienced executive put it this way: “You always feel you can fix anything. But you can’t. And you can’t let [personnel issues] fester.

If [some people on the team] are not performing, their peers know it and your peers know it.” A good rule of thumb is that you should decide by the end of your first 90 days who will remain and who will go. By the end of six months, you should have communicated your planned personnel changes to key stakeholders, especially your boss and HR. If you wait much longer, the team becomes “yours” and change becomes increasingly difficult to justify and carry out. Naturally, the time frame depends on the STARS situation you are confronting: It may be shorter in a turnaround and longer in a sustaining-success situation. The key is to establish some deadlines for reaching conclusions about your team and taking action within your 90-day plan, and then to stick to them.

Not repairing the airplane.

Unless you are in a start-up, you do not get to build a team from scratch: You inherit a team and have to mold it into what you need to achieve your A-item priorities. The process of molding a team is like repairing an airplane in midflight. You will not reach your destination if you ignore the necessary repairs. But you do not want to crash the airplane while trying to fix it. This situation can present a dilemma: It is essential to replace people, but some of them are essential to help run the business in the short run. What do you do? You develop options as quickly as you can.