The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (16 page)

Read The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt Online

Authors: T. J. Stiles

Tags: #United States, #Transportation, #Biography, #Business, #Steamboats, #Railroads, #Entrepreneurship, #Millionaires, #Ships & Shipbuilding, #Businessmen, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #History, #Business & Economics, #19th Century

Newly mobile, self-interested, unbound by the old culture of deference, this emerging nation of strangers gave rise to an aggressive spirit of enterprise. They called it “go-ahead.” It became a New York catchphrase, for this business-minded city began to overflow with the chosen people of go-ahead, the New England Yankees. From farmboys to clerks to merchants, they invaded Manhattan and made it the capital of “the universal Yankee nation,” as P. T. Barnum called it.

Fiercely calculating, afloat in a sea of drifting people who knew nothing of each other's character, the Yankees of New York and New England crafted new values to suit the age of the marketplace. To outsiders—English aristocrats, for example—they seemed to be “uncouth and curious rustics,” one historian writes, “whose energies were exclusively given over to the pursuit of the main chance.” In the course of two years in America, Frances Trollope learned the Yankee character well, and concluded that they cherished no attribute more highly than sharp dealing, better known as being “smart.”

“I like them extremely well,” she wrote of Yankees, “but I would not wish to have any business transactions with them, if I could avoid it, lest, to use their own phrase, ‘they should be too smart for me.’” On her first visit to New York in the late 1820s, she “neglected” to strike a deal with a carriage driver before the ride, and was forced to pay an exorbitant sum. “When I referred to the waiter of the hotel, he asked if I had made a bargain. ‘No.’ ‘Then I expect’ (with the usual look of triumph) ‘that the Yankee has been too smart for you.’” Americans from other regions, she wrote, described them “as sly, grinding, selfish, and tricking. The Yankees… will avow these qualities themselves with a complacent smile, and boast that no people on earth can match them at over-reaching in a bargain.” It was a curious kind of vanity, she observed; if you listened to a Yankee describe himself, “you might fancy him a god—though a tricky one.”

35

Cornelius Vanderbilt needed every ounce of shrewdness in the enterprise he now embarked on. In May 1829, he sealed an arrangement with some stagecoach men and Captain Wilmon Whilldin on the Delaware to form the Dispatch Line, providing through service between New York and Philadelphia via New Brunswick and Trenton. The gatekeeper on the turnpike tracked the line's rising tolls as the

Citizen

carried ever more passengers: $19.30 in May, $73.75 in June, $126.22 in July, $157 in August. Vanderbilt stretched his resources to the limit to purchase more steamboats: his old favorite, the

Bellona;

the rebuilt

Emerald

(which he sent around Cape May to run on the Delaware); and the

Baltimore

and

the John Marshall

in early 1830. Now the master of a mostly secondhand fleet, with his brother Jacob and cousin John as captains, Vanderbilt carried the battle to the competition—who were none other than the new owners of the Union Line. A rate war broke out; the fare to Philadelphia plunged to a dollar, including free meals on board.

36

Then, at the start of the 1831 season, the Dispatch Line would take a startling turn.

NOTHING ENTIRELY DISAPPEARS

in history. The threads of tattered old fabric—especially social fabric—are ever woven into new tapestries. While Vanderbilt wrestled with his pickpocket in New York, his competitors plotted in their gardens to remake the culture of deference—or, at least, to maintain some sort of continuity, to impose some kind of order on the chaos of the marketplace.

Their gardens could be reached from New York only by boat, a special steam ferry that carried world-weary city folk across the Hudson to enjoy their splendor. Indeed, the name of this resort became a synonym for tranquil beauty:

Hoboken

. All 564 acres of the place belonged to Colonel John Stevens, who with his sons had long been Vanderbilt's allies, and now were his rivals.

The Stevenses were what the Livingstons might have been—patricians who successfully made the transition to this more individualistic, commercial, and ruthless age. Colonel Stevens, in fact, was the late Chancellor Livingston's brother-in-law. Like the chancellor, he dabbled in the sciences; and like the chancellor, he dabbled with little real ability, though he freely appropriated the inventions of those who worked for him. The Livingstons' monopoly had forced him to send his first steamboat to the Delaware; his sons (John, Robert, Edwin, and James) soon dominated that river with more and better boats, and collaborated with Gibbons on the Union Line.

The sons inherited the colonel's technological interests, but with actual mechanical talent. Robert L. (for Livingston) Stevens proved to be one of the great engineers of the day, repeatedly improving steamboat design. The brothers mastered business competition as well, in sharp contrast to the Livingstons, whose North River Steamboat Company failed in 1826—whereupon the Stevenses immediately began to run their own boats from New York to Albany. In New Jersey, they took over the Union Line from William Gibbons, purchasing the

Thistle

and the

Swan

. In 1829 they drove the Citizen's Line into extinction. They intended to do the same to Vanderbilt's upstart Dispatch Line.

37

Their strategy involved far more than free meals and discounted fares: they intended to make the stagecoach obsolete. As far back as 1812, the colonel had published a pamphlet proposing that a steam engine be put on wheels and pull a train of carriages on a road of rails. By the late 1820s, the “rail road” had become reality on such lines as New York's Mohawk & Hudson. The Stevenses reasoned that it was the perfect replacement for the bone-rattling stagecoach ride across New Jersey's turnpikes, and so they collected investors to build one. And, along with capital, they sought something the chancellor would have approved of: a legal monopoly.

This was not the eighteenth century, however, and this would not be a copy of the Livingston monopoly. For one thing, the family worked through a corporation chartered by the state legislature—the Camden & Amboy Railroad—with publicly traded shares. For another, the Stevenses faced fierce opposition from other interests, including the organizers of the Delaware & Raritan Canal, led by Robert F. Stockton, a wellborn navy lieutenant who was a swashbuckler at sea and in business alike. Stockton maneuvered the Stevenses into merging their well-financed railroad with his undercapitalized canal on February 15, 1831, creating the “Joint Companies,” as the enterprise was known. The immense size of this new entity gave it the leverage to extract a remarkable bounty from the legislature: “That it shall not be lawful… to construct any other railroad or railroads in this State, without the consent of said companies.” By signing over such a valuable piece of its sovereignty to a consortium of wealthy men, New Jersey earned the snide nickname “the Camden & Amboy State.” The price for its virtue was an annual fee of $30,000 and a limit of $3 on the through fare (three times what Vanderbilt charged). The Stevenses had finally brought order out of the anarchy of competition—or

bought

order, to be precise.

38

At just about this time the Dispatch Line disappeared. The standing assumption has always been that the Stevens brothers bribed Vanderbilt. According to an old New Brunswick mariner, “It was said they bought him off here and yonder and made him rich.” The payoff was motivated by fear, the man claimed; Vanderbilt “fought 'em so hard that he left here with a reputation that scared people.”

39

Tough, shrewd, and frugal, Phebe Vanderbilt strongly influenced her son Cornelius, who revered her. Of English descent, she married into an old Dutch family on Staten Island. Her husband ran a small farm and a sailboat ferry to Manhattan; she earned her own money, which she lent out at commercial rates of interest.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society

The Staten Island of Vanderbilt's youth was a rural landscape at the mouth of busy New York Harbor. This 1833 view from the Narrows captures both the shipping and the undeveloped hillsides behind the Quarantine, the state hospital for immigrants. Young Vanderbilt ran a sailboat ferry like the one shown here.

Library of Congress

Hardworking, modest, beloved by her offspring, Sophia Johnson Vanderbilt was Cornelius's first wife and cousin. Their early years together weren't always easy, yet their intimacy grew over time, as they traveled together and grappled with family turmoil.

Biltmore Estate

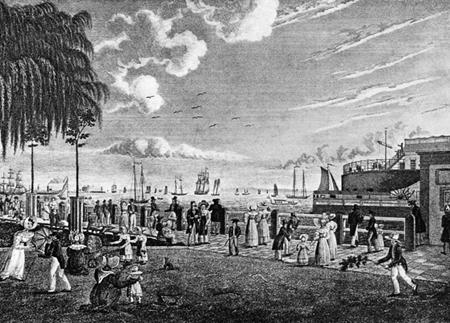

New York Harbor, as seen in 1830 from the Battery, the promenade at the southern tip of Manhattan. Staten Island lies directly across the bay; to the right is the curved battlement of Castle Clinton, just offshore, later enclosed by landfill. The abundant shipping and display of fashion depicted here drew much comment from visitors.

Collection of the New-York Historical Society

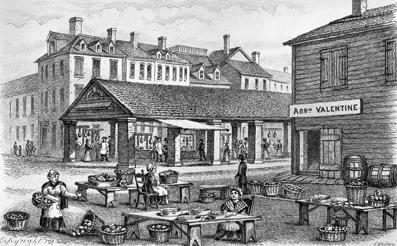

The open-air Fly Market, shown here in 1816, represented the sphere that Sophia Vanderbilt occupied after the young couple moved to New York during the War of 1812. As seen here, women both sold and purchased goods amid the densely built-up city, where packs of pigs and dogs roamed freely

Collection of the New-York Historical Society