The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (87 page)

Read The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt Online

Authors: T. J. Stiles

Tags: #United States, #Transportation, #Biography, #Business, #Steamboats, #Railroads, #Entrepreneurship, #Millionaires, #Ships & Shipbuilding, #Businessmen, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Rich & Famous, #History, #Business & Economics, #19th Century

Victoria Woodhull used the fame of her purported brokerage house to take a leading role in the women's movement. Shown here addressing a committee of Congress (with her sister on her left), she declared herself a candidate for president in 1872. The sisters also launched

Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly

, devoted to spiritualism and radical causes. Though some have assumed that Vanderbilt supported the periodical, he did not.

Library of Congress

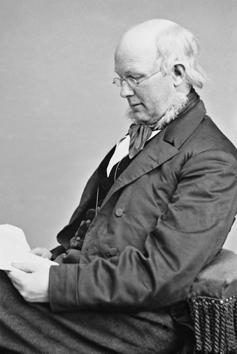

Founder of the

New York Tribune

, Horace Greeley played a unique role in American public life. He befriended Vanderbilt's gambling-addicted son Corneil, and lent him tens of thousands of dollars. Greeley convinced Vanderbilt to serve as bondsman for the release of Jefferson Davis in 1867, which started him on the path toward his endowment of Vanderbilt University.

Library of Congress

Vanderbilt's second wife, Frank Crawford Vanderbilt, was also his cousin. A native of Mobile, Alabama, Frank was a thirty-year-old divorcée when she gained the Commodore's acquaintance in 1868. A year later, they made a trip to Canada for a private wedding—after she signed a prenuptial agreement. A dignified woman with an aristocratic air, she brought her often-difficult husband fully into elite society.

Albany Institute of History and Art

Vanderbilt's daughter Ethelinda married Daniel B. Allen, who served as a manager of his father-in-law's businesses for three decades. The Allens lived on Staten Island, not far from William H. Vanderbilt's farm. A permanent rift opened between the Commodore and the Allens in 1873 when Vanderbilt refused to save their son when his brokerage house failed.

Albany Institute of History and Art

Vanderbilt's daughter Sophia married Canadian merchant Daniel Torrance, who ran his father-in-law's transatlantic line and served as vice president of the New York Central Railroad. Described by one nephew as “impulsive,” Sophia criticized Frank behind her back. On his deathbed, Vanderbilt insisted that Sophia apologize and shake hands with Frank.

Albany Institute of History and Art

Mary, another Vanderbilt daughter, married Nicholas B. La Bau, a lawyer and politician. Mary led the resistance to Vanderbilt's will, in which he left most of his estate to William. “Now don't be stubborn and give trouble,” Vanderbilt told her on his deathbed. “I have left you all enough to live like ladies.” Unsatisfied with

$500,000

worth of bonds, she challenged the will, leading to a long court battle.

Albany Institute of History and Art

When Seymour Guy painted

Going to the Opera

in 1873, William and his wife Maria had already begun to establish their large family in patrician society, as shown here by the fine art that William purchased on repeated trips to Europe. The Commodore cultivated William's oldest sons, Cornelius II and William K.

Biltmore Estate

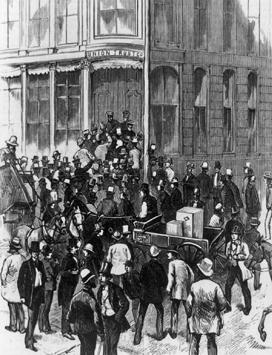

The Panic of 1873 posed the greatest crisis of Vanderbilt's career. His son-in-law Horace F. Clark had dangerously increased the debt of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, and had embroiled both it and a major bank, the Union Trust Company, in his personal stock speculations. The Union Trust had to close its doors in the face of a run (shown here) during the Panic.

Library of Congress

Vanderbilt turned eighty in 1874. This engraving—made from a photograph taken for

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Monthly

in early 1876—shows him at rest in his house at 10 Washington Place. He holds a young descendant, likely a great-grandchild, demonstrating a warmth that outsiders rarely saw.

New York Central System Historical Society

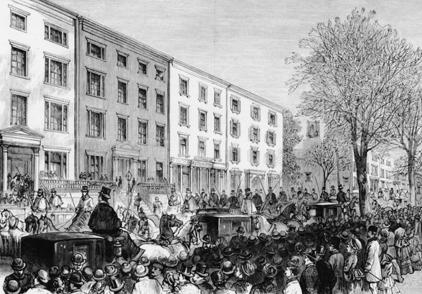

Vanderbilt's final illness began in May 1876, and he remained bedridden until his death on January 4, 1877. Though he was in agony for much of this period, his mind remained clear until very near the end. Here crowds are shown outside his double-wide house between Mercer and Greene streets, at 10 Washington Place, after word of his death.

Library of Congress