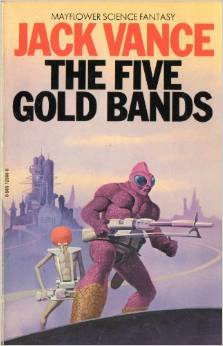

The Five Gold Bands

Jack Vance

The tunnel ran through layers of red and gray sandstone cemented with silica—tough digging even with the patent grab-compactor. Twice Paddy Blackthorn had broken into old wells, once into a forgotten graveyard. Archaeologists would have chewed their fingernails to see Paddy crunching aside the ancient bones with his machine. Three hundred yards of tunnel and the last six feet were the worst—two yards of feather-delicate explosive, layers of steel, copper, durible, concrete, films of guard circuits.

Edging between the pockets of explosive, melting out the steel, leaching the concrete with acid, tenderly shorting across the alarm circuits, Paddy finally pierced the last layer of durible and pushed up the composition flooring.

He hauled himself up into the most secret spot of the known universe, played his flash around the room.

Drab concrete walls, dark floor—then the light glinted on ranks of metal tubes. “Doesn’t that make a pretty sight, now,” Paddy murmured raptly.

He moved—the light picked out a cubical frame supporting complexities of glass and wire, placket and durible, metal and manicloid.

“There it

is!

” said Paddy, his eyes lambent with triumph. “Now if only I could pull it back out the tunnel, then wouldn’t I lord it over the high and mighty!… But no, that’s a sweet dream; I’ll content myself with mere riches. First to see if it’ll curl out the blue flame…”

He stepped gingerly around the mechanism, peering into the interior. “Where’s the button that says ‘Push’… There’s no clues—ah,

here!

” And Paddy advanced on the control panel. It was divided into five segments, each of which bore three dials calibrated from 0 to 1,000 and, below, the corresponding control knobs. Paddy inspected the panel for a moment, then turned back to the machine.

“There’s the socket,” he muttered, “and here’s one of the pretty bright tubes to fit… Now I throw the switches—and if she’s set on the right readings, then I’m the most fortunate man ever out of Skibbereen, County Cork. So—I’ll try her out.” On each of the five panels he flung home the switches and stood back, playing his light expectantly on the metal tube.

Nothing happened. There was no quiver of energy, no flicker of sky-blue light whirling into a core down the center of the tube.

“Sacred heart!” muttered Paddy. “Is it that I’ve tunnelled all this time for the joy of it? Och, there’s one of three things the matter. The power’s disconnected or there’s a master switch yet to be thrown. Or third and worst the dials are at their wrong settings.” He rubbed at his chin. “Never say die, it’s the power. There’s none coming into the entire gargus.” He turned his light around the room. “Now there’s the power leads and they run into that little antechamber.”

He peered through the arch. “Here’s the master switch and just as I told all who had ears to listen it’s open. Now—I’ll close it and then we’ll see… Whisht a while. First am I safe? I’ll stand behind this bar-block and push home with this bit of pipe. Then I’ll go in and play those dials like Biddy on the bobbins.”

He pushed. In the other room fifteen tongues of purple flame curled frantically out of the metal tube, lashed at the walls, fused the machinery, flung masonry at the bar-block, made chaos in a circle a hundred feet wide.

When the Kudthu guards probed the wreckage Paddy was struggling feebly behind the dented bar-block, a tangle of copper tubing across his legs.

Akhabats’ jail was a citadel of old brown brick, hugging the top of Jailhouse Hill like a scab on a sore thumb. Dust and the dull texture of the bricks gave the illusion of ruins, baking to rubble in the heat of Prosperus. Actually, the walls stood thick, cool, firm. Below to the south lay the dingy town. To the north were the Akhabats spaceyards. Beyond stretched the plain, flat and blue as mildew—as far as the eye could reach.

The Kudthu jailer woke Paddy by running horny fingers along the bars. “Earther, wake up.”

Paddy arose, feeling his throat “No need to break a man’s sleep for a hanging. I’d be here in the morning.”

“Come, no talk,” rumbled the jailer, a manlike creature eight feet tall with rough gray skin, eyes like blue satin pincushions where a true man’s cheeks would have been.

Paddy stepped out into the aisle, followed the jailer past rows of other cells, whence came snores, rumblings, the luminous stare of eye, the hiss of scale on stone.

He was taken to a low brick-walled room, cut in half by a counter of dark bronze wax-wood. Beyond, around a long low table, sat a dozen figures more or less manlike. A mutter of conversation died as Paddy was brought forward and a row of eyes swung to stare at him.

“Ah, ye sculpins,” muttered Paddy. “So you’ve come all the way to jeer at a poor Earther and his only sin was stealing space-drives. Well, stare then and be damned!” He squared his shoulders, glanced down the long table from face to face.

The Kudthu jailer pushed Paddy a little forward, and said, “This is the talker, Lord Councillors.”

The hooded Shaul Councillor, after a moment’s scrutiny, said in the swift Shaul dialect, “What is your crime?”

“There’s no crime, my Lord,” replied Paddy in the same tongue. “I am innocent. I was but seeking my ship in the darkness and I fell into an old well and then—”

The jailer said, fumbling the words, “He was trying to steal space-drives, Lord Councillor.”

“Mandatory death.” The Shaul raked Paddy with eyes like tiny lights. “When is the execution?”

“Tomorrow, Lord, by hanging.”

“The trial was over-hasty, Lord,” exclaimed Paddy. “The famous Langtry justice has been scamped.”

The councillor shrugged. “Can you speak each of the tongues of the Line?”

“They’re like my own breath, Lord! I know them like I know the face of my old mother!”

The Shaul Councillor sat back in his seat. “You speak Shaul well enough.”

The Koton Councillor spoke in the throaty Koton speech. “Do you understand me?”

Paddy replied, “Indeed I believe I am the only Earther alive that appreciates the beauty of your lovely tongue.”

The Alpheratz Eagle asked the same question in his own lip-clacking talk. Paddy responded fluently.

The Badau and the Loristanese each spoke and Paddy replied to each.

There was a moment of silence during which Paddy looked right and left, hoping to seize a gun from a guard and kill all in the room. The guards wore no guns.

The Shaul asked, “How is it you are master of so many tongues?”

Paddy said, “My Lord, it’s a habit with me. I’ve been journeying space since I was a lad and no sooner am I hearing strange speech than I’m wondering what’s going on. And may I ask why it is you’re questioning me? Are you grooming me for a pardon perhaps?”

“By no means,” replied the Shaul. “Your offense is beyond pardon, it cuts at the base of the Langtry power. The punishment must be severe, to deter future offenders.”

“Ah, but your Lordships,” Paddy remonstrated, “it’s you Langtrys who are the offenders. If you allowed your poor cousins on Earth more than our miserable ten drives, then a stolen drive would not bring a million marks and there’d be no temptation for us poor unfortunates.”

“I do not set the quotas, Earther. That is in the hands of the Sons. Besides there are always scoundrels to steal ships and unmounted drives.” He fixed Paddy with a significant glance.

The Koton Councillor said abruptly, “The man is mad.”

“Mad?” The Shaul studied Paddy. “I doubt it. He is voluble—irreverent—unprincipled. But he appears sane.”

“Unlikely.” The Koton swung his thin gray-white arm across the table handed the Shaul a sheet of paper. “This is his psychograph.”

The Shaul studied it and the skin of his cowl rippled slowly.

“It is indeed odd… unprecedented… even allowing for the normal confusion of the Earth mind…” He glanced at Paddy. “Are you mad?”

Paddy shrugged. “I take it I’d hang in any event.”

The Shaul smiled grimly. “He is sane.” He looked around at his fellows. “If there is no further objection then…” None of the Councillors spoke. The Shaul turned to the jailer.

“Handcuff him well, blindfold him—have him out on the platform in twenty minutes.”

“Where’s the priest?” yelled Paddy. “Get me the Holy Father from Saint Alban’s. Are you for hauling me up without the sacrament?”

The Shaul gestured. “Take him.”

Muttering wild curses Paddy was handcuffed, blindfolded, crow-legged out into the sharp night air. The wind, smelling of lichen, dry oil-grass, smoke, cut at his face. They led him up a ramp into a warm interior that felt solid, metallic. Paddy knew by the smell, compounded of oil, ozone, acryl varnish, and by the vague throb and vibration of much machinery, that he was aboard a large ship of space.

They led him to the cargo hold, removed the handcuffs, the blindfold. He looked wildly toward the door but the way was blocked by a pair of Kudthu attendants, watching him with blue-bottle eyes. So Paddy relaxed, stretched his sore muscles. The Kudthu attendants departed, the port swung shut, the dogs scraped down tight on the outside.

Paddy inspected his quarters—a metal-walled room about twenty feet in each direction, empty except for his own person.

“Well,” said Paddy, “there’s nothing to it. Complaints and protests will do me no good. If them Kudthu devils had been a quarter-ton lighter apiece, there might have been a fight.”

He lay on the floor and presently the ship trembled, took to the air. The steady drone of the generator permeated the metal and Paddy went to sleep.

He was roused by a Shaul in the pink and blue garb of the Scribe caste. The Shaul was about his own size with a head shrouded by a cowl of fish-colored skin. It was attached at his shoulders, his neck, the hack of his scalp and projected over his forehead in a widow’s-peak of flexible black flesh. He carried a tray which he set on the floor beside Paddy.

“Your breakfast, Earther. Fried meat with salt, a salad of bog-greens.”

“What kind of meat?” demanded Paddy “Where did it come from? Akhabats?”

“Stores came aboard at Akhabats.” admitted the Shaul.

“Away with it, you hooded scoundrel! There’s never a bite of meat on the planet except that of the Kudthus that’s died of old age. Be off with your cannibal food!”

The Shaul flapped his cowl without rancor. “Here’s some fruit and some yeast cake and a pot of hot brew.”

Grumbling, Paddy ate his breakfast, drank the hot liquid. And the Shaul watched him with a smile.

Paddy looked up, frowned. “And why then your crafty “I merely observe that you appear to enjoy that broth.”

Paddy set down the cup, coughed and spat. “Ah, you devil. Once that your tribe broke loose from Earth they forgot all decency and manners. Would I be feeding you with ghoul-food? Would I now, was we reversed?”

“Meat is meat,” observed the Shaul, gathering the utensils. “You Earthers are oddly emotional about trivialities.”

“By no means,” declared Paddy. “We’re the civilized ones of the universe in spite of your pretensions. It’s you far-off heathens that have brought Mother Earth to her knees.”

“Old stock must give way to newer types,” said the Shaul mildly. “First the Pithecanthropi, then the Neanderthals, now the Earthers.”

“Pah!” Paddy spat. “Give me thirty feet of flat ground with a bit of spring to it and I’ll whip any five of you skinheads and any two of them Kudthu hunks.”

The Shaul smiled faintly. “You Earthers don’t even thieve well. After two months tunneling you’re not five minutes in the building before you blow it up. Lucky there was only a trickle of current coming in or you’d have flattened the city.”

“Sorry,” sneered Paddy. “We Earthers only invented space-drive in the first place.”

“Langtry discovered space-drive—and that by accident.”

“And where’d you be without him?” asked Paddy. “You freak races are coasting on what old Earth gave out to you in the first place.”

Said the Shaul, smiling, “Answer me this—what may be the fifth root of a hundred and twelve?”

“Let me ask you,” said Paddy craftily, “because you worked the sum just now before you came in. Now give me the seventh root of five thousand.”

The Shaul closed his eyes, brought into his visual imagination a mental picture of a slide-rule, manipulated it mentally, read the answer. “Somewhere between three point three seven and three point three eight.”

“Prove it,” Paddy challenged.

“I’ll give you a pencil and paper and you may prove it,” said the Shaul.

Paddy compressed his lips. “Since you’re so knowledgeable perhaps you’ll know where we’re off to and what it is they’re wanting with me?”

“Certainly,” said the Shaul. “The Sons of Langtry are holding their yearly council and you are to interpret for them.”

“Sacred heart! gasped Paddy. “How is this again?”

The Shaul said patiently, “Every year the Sons from the Five Worlds meet to arrange quotas and distribution of space-drives. Since regrettably there is jealousy and suspicion between the Five Worlds no single tongue is spoken. The Sons of the other four worlds would lose face.

“An interpreter is an easy expedient. He translates every word into four other tongues. The Sons gain time to reflect, there is complete impartiality and no damage to planetary The Shaul laughed silently a moment, then continued. The interpreter, you must understand, performs no critical service since each of the Sons knows—to some extent—the tongue of the other four. He is merely a symbol of equality and even-based cooperation, a lubricant between the easily offended Sons.”

Paddy rubbed his chin doubtfully. He said in a hushed voice, “But this proceeding is the secret of the galaxy. No one knows when or where it occurs. It’s like the redezvous of shameful lovers for the secrecy.”

“Correct,” said the Shaul. He eyed Paddy with bright meaningful eyes. “As you may be aware, many of the archaic races are dissatisfied with the quotas; the Sons of Langtry gathered together make a tempting target for assassination.”

Paddy gestured expressively. “Why am I selected for the honor? Surely there are others fully equal to the honor?”

“Yes indeed,” agreed the Shaul. “I, for instance, speak each of the five tongues fluently. However I am no criminal condemned to death.”