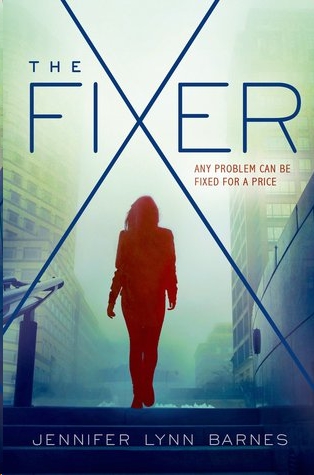

The Fixer

Authors: Jennifer Lynn Barnes

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Family, #Siblings, #Law & Crime, #Mysteries & Detective Stories, #General

For Allison, sister-in-law extraordinaire

CONTENTS

As far as I could tell, my history teacher had three passions in life: quoting Shakespeare, identifying historical inaccuracies in cable TV shows, and berating Ryan Washburn. “Eighteen sixty

-

three, Mr. Washburn. Is that so hard to remember? Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in eighteen sixty-

three

.”

Ryan was a big guy: a little on the quiet side, a little shy. I had no idea what it was about him that had convinced Mr. Simpson he needed to be taken down a notch—or seven. But more and more, this was how history class went: Simpson called on Ryan, repeatedly, until he made a mistake. And then it began.

As Mr. Simpson railed on, Ryan stared at his desk, his head bowed so far that his chin gouged his collarbone. Sitting directly to his left, I could see the tension in his shoulder muscles, the sweat starting to bead up on his neck.

My grip on my pencil tightened.

“Where is that

incredible promise

I hear my colleagues chatting about in the teachers’ lounge?” Mr. Simpson asked Ryan

facetiously. “You have a lot of fans at this school, Mr. Washburn. Surely they can’t all be mistaken about your intellectual capacity. Perhaps the emancipation of every enslaved human being in this country is simply not significant enough to merit a student of your

remarkable

caliber taking note of the date?”

“I’m sorry,” Ryan mumbled. His Adam’s apple bobbed.

Something inside me snapped. “It wasn’t all of the slaves,” I said evenly.

Mr. Simpson’s eyes narrowed and flicked over to me. “Did you have something to share with the class, Ms. Kendrick?”

“Yes.” I’d long since shed the Southern accent I’d had when I’d moved to Montana at the age of four, but I still had a habit of taking my time with my words. “The Emancipation Proclamation,” I continued, at my own languid pace, “only freed slaves in the Confederate states. The remaining nine hundred thousand slaves weren’t freed until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in eighteen sixty-

five

.”

A muscle in Mr. Simpson’s jaw ticked. “ ‘The fool doth think he is wise,’ Ms. Kendrick, ‘but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.’ ”

I’d been up working since five that morning. Beside me, Ryan still hadn’t managed to raise his gaze from his desk.

I leaned back in my seat. “Methinks the lady doth protest too much.”

“Want to tell me why you’re here?” The guidance counselor scrolled through my file. When I didn’t provide an immediate answer, she looked up from the computer, folded her hands on the desk, and leaned forward. “I’m concerned, Tess.”

“If you’re talking about the way Mr. Simpson victimizes his most vulnerable students, I am, too.”

The words

victimize

and

vulnerable

were guidance counselor kryptonite. She pressed her lips together in a thin line. “And you think

inappropriate backchat

”—she read the phrase off the slip Mr. Simpson had written me—“is the most constructive way of expressing your concerns?”

I decided that was a rhetorical question.

“Tess, this time last year, you were on the girls’ track team. You had nearly perfect attendance. You were, by all reports, sociable enough.”

Not

sociable

, but

sociable enough.

“Now I’m getting reports of you falling asleep in class, skipping assignments. You’ve already missed five days this semester, and we’re not even three weeks in.”

I shouldn’t have stayed home when I had the flu

, I thought dully. I’d given myself two days to recover. With absences racking up, that was two days too many.

I should have kept my mouth shut in Simpson’s class.

I couldn’t afford to draw attention to myself. To my situation. I knew that.

“You quit the track team.” The guidance counselor was relentless in her onslaught. “You no longer seem to associate with any of your peers.”

“My peers and I don’t have much in common.”

I’d never been popular. But I used to have friends—people to sit with at lunch, people who might ask questions if they thought something was wrong.

And that was the problem. These days, friends were a luxury I couldn’t afford.

It was easy enough to make people give up on you if that was the goal.

“I’m afraid I have no choice but to call your grandfather.” The guidance counselor reached for the phone.

Don’t

, I thought. But she was already dialing. I gritted my teeth to keep from reacting and tipping my hand. I forced myself to breathe. Gramps probably wouldn’t answer. If he did, if it went badly, I already had a stack of excuses ready to go.

You must have caught him getting up from a nap.

It’s this new medication his doctor has him on.

He’s not much of a phone person.

The fifteen or twenty seconds it took her to give up on someone answering were torture. My heart still pounding in my ears, I pushed back the urge to shudder with relief. “You didn’t leave a message.” My voice sounded amazingly calm.

“Messages get deleted,” she said dryly. “I’ll try again later.”

The knots in my stomach tightened. I’d dodged a bullet. But with Gramps the way he was, I couldn’t afford to sit around and wait for round two. She wanted me to talk. She wanted me to

share

. Fine.

“Ryan Washburn,” I said. “Mr. Simpson has it in for him. He’s a nice kid. Quiet. Smart.” I paused. “He leaves that class every day feeling stupid.”

It shouldn’t have been my job to tell her this.

“Do you know what we do out at my grandfather’s ranch? Other than raise cattle?” I caught her gaze, willing her not to look away. “We take in the horses no one else wants, the ones who’ve been abused and broken and shattered inside until there’s nothing left but

animal anger

and

animal fear

. We try to

break through that. Sometimes we win.” I paused. “Sometimes we don’t.”

“Tess—”

“I don’t like bullies.” I stood to leave. “Feel free to call my grandfather and tell him that. I’d say it’s a good bet he already knows.”

My gamble appeared to have paid off. The phone didn’t ring that night. Or the next. I kept a low profile at school. I got up early, stayed up late, and held my world together through sheer force of will. It wasn’t much of a routine, but it was mine. By Thursday afternoon, I’d stopped expecting the worst.

That was a mistake.

Standing in the middle of the paddock, my feet planted wide and my arms hanging loose by my sides, I eyed the horse channeling Beelzebub a few feet away. “Hey now,” I said softly. “That’s not very ladylike.”

The animal’s nostrils flared, but she didn’t rear back again.

“Someday,” I murmured, my voice edging up on a croon, “I’d like to meet your first owner in a dark alleyway.” Behind me, the sound of creaking wood alerted me to the arrival of company. I half expected that to send the horse into another fit, but instead, the animal took a few hesitant steps toward me.

“She’s beautiful.”

I froze. I recognized that voice—and instantly wished that I hadn’t.

Two words.

After all this time, that was all it took.

My chest tightened.

“I’ll be a while,” I said. I didn’t let myself turn around. This particular visitor wasn’t worth getting riled up over.

“It’s been too long, Tess.”

Whose fault is that?

I didn’t bother responding out loud.

“You’re good with her. The horse.” Ivy didn’t sound the least bit angry at being ignored. That was the way it was with her—sugar and spice and everything nice, right up to the point when she wasn’t.

Go away

, I thought. The horse in front of me gave a violent jerk of her head, picking up on the tension in my body. “Hey,” I murmured to her. “Hey now.” She slammed her front hooves into the ground. I got the message and began to back away.

“We need to talk,” Ivy told me when I reached the outer limits of the paddock. Like her presence on the ranch was an everyday occurrence. Like talking was something the two of us did.

I jumped the fence. “I need a shower,” I countered.

Ivy could not argue with my logic. Or more likely, she chose not to. I had the sense that the great Ivy Kendrick was the kind of person who could successfully argue just about any point—but what did I know? It had been almost three years since the last time I’d seen her.

“After your shower, we need to talk.” Ivy was nothing if not persistent. I deeply suspected that she wasn’t used to people telling her no. Luckily, there were benefits to being the kind of person known for taking my time with words. I didn’t

have

to say no. Instead, I walked toward the house, my stride outpacing hers, even though she had an inch or two on me.

“I got a call from your guidance counselor,” Ivy said behind me. “And then I made some calls of my own.”

Her words didn’t slow me down, but my gut twisted like a wet towel being wrung out and then wrung out again.

“I talked to the ranch hands,” Ivy continued.

I climbed up on the front porch, flung open the door, and let it slam behind me when I’d stepped inside. There was a time when slamming a door would have drawn my grandfather’s attention. He would have called me a heathen, threatened to scalp me, and sent me back out onto the porch to “try again.”