The Food of a Younger Land (15 page)

Read The Food of a Younger Land Online

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

This journey by time capsule to the early 1940s is not always a pleasant one. It affords us a glimpse at the pre-civil rights South. This was true in the raw copy of the guidebooks as well. The Alabama guidebook copy referred to blacks as “darkies.” It originally described the city of Florence struggling through “the terrible reconstruction, those evil days when in bitter poverty, her best and bravest of them sleep in Virginia battlefields, her civilization destroyed . . . And now when the darkest hour had struck, came a flash of light, the forerunners of dawn. It was the Ku Klux Klan . . .” The Dover, Delaware, report stated that “Negroes whistle melodiously.” Ohio copy talked of their “love for pageantry and fancy dress.” Such embarrassingly racist passages were usually edited out, but the

America Eats

manuscripts are unedited, so the word

darkies

remains in a Kentucky recipe for eggnog. In the southern essays from

America Eats

, whenever there is dialogue between a black and a white, it reads like an exchange between a slave and a master. There also seems to be a racist oral fixation. Black people are always sporting big “grins.” A description of a Mississippi barbecue cook states, “Bluebill is what is known as a ‘bluegum’ Negro, and they call him the brother of the Ugly man, but personal beauty is not in the least necessary to a barbecue cook.” And in the memos and correspondence there are traces of anti-Semitism, such as the suggestion that the New York writings about Jewish traditions be cut from the book because they were not truly American. That one was quickly refuted by the FWP staff.

America Eats

manuscripts are unedited, so the word

darkies

remains in a Kentucky recipe for eggnog. In the southern essays from

America Eats

, whenever there is dialogue between a black and a white, it reads like an exchange between a slave and a master. There also seems to be a racist oral fixation. Black people are always sporting big “grins.” A description of a Mississippi barbecue cook states, “Bluebill is what is known as a ‘bluegum’ Negro, and they call him the brother of the Ugly man, but personal beauty is not in the least necessary to a barbecue cook.” And in the memos and correspondence there are traces of anti-Semitism, such as the suggestion that the New York writings about Jewish traditions be cut from the book because they were not truly American. That one was quickly refuted by the FWP staff.

While the racist attitudes of the old South are in evidence here, and are even more in evidence in some of the pieces that are not included, there is also an overall difference in the way southern food was regarded in the time of

America Eats

and the view today. While the old view was that African-American cooking was an interesting and colorful addition to the southern tradition, food writers today generally find that southern food

is

African American to its roots. A great many of the cooks, including some of the most influential, were black.

America Eats

and the view today. While the old view was that African-American cooking was an interesting and colorful addition to the southern tradition, food writers today generally find that southern food

is

African American to its roots. A great many of the cooks, including some of the most influential, were black.

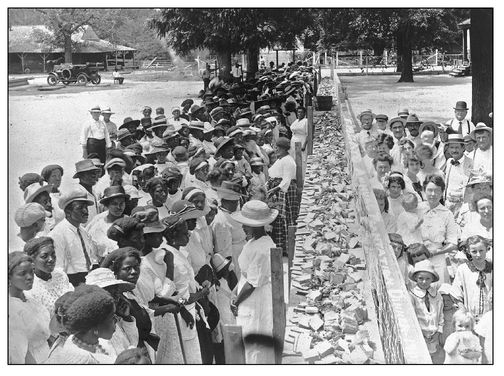

F. M. GAY’S ANNUAL BARBECUE GIVEN ON HIS PLANTATION EVERY YEAR.

Mississippi Food

EUDORA WELTY

Eudora Welty was born in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1909. After two years at the Mississippi State College for Women, encouraged by her parents, she went to study English at the University of Wisconsin. After graduating in 1929 she spent a year at Columbia University, studying advertising. She returned to Mississippi to start a writing career, producing short stories on Mississippi life. Her first story, “Death of a Traveling Salesman,” a touching story in which a salesman discovers the importance of family, was published in 1936, in a small magazine called

Manuscript.

But when her father died suddenly, she sought advertising jobs to earn money.

Manuscript.

But when her father died suddenly, she sought advertising jobs to earn money.

The following was a mimeographed pamphlet that she wrote for the Mississippi Advertising Commission and which they distributed. The FWP could have had little notion of Welty’s future when they selected this piece, possibly Welty’s only piece of food writing. At the time of the

America Eats

project her career was beginning to develop, and her first collection was published in 1941. The Mississippi Writers’ Project probably knew of her from her work in advertising for the WPA in Mississippi. A year later, when the project was closed, Welty would win her first O. Henry Prize and a Guggenheim Award. Welty went on to become one of America’s most distinguished southern writers. Before her death in 2001, she had won six O. Henry Awards for Short Stories, a National Medal for Literature, a Pulitzer Prize, and France’s highest honor, the Legion of Honor.

America Eats

project her career was beginning to develop, and her first collection was published in 1941. The Mississippi Writers’ Project probably knew of her from her work in advertising for the WPA in Mississippi. A year later, when the project was closed, Welty would win her first O. Henry Prize and a Guggenheim Award. Welty went on to become one of America’s most distinguished southern writers. Before her death in 2001, she had won six O. Henry Awards for Short Stories, a National Medal for Literature, a Pulitzer Prize, and France’s highest honor, the Legion of Honor.

S

tark Young, in his book

Feliciana

, tells how a proud and lovely Southern lady, famous for her dinner table and for her closely-guarded recipes, temporarily forgot how a certain dish was prepared. She asked her Creole cook, whom she herself had taught, for the recipe. The cook wouldn’t give it back.

tark Young, in his book

Feliciana

, tells how a proud and lovely Southern lady, famous for her dinner table and for her closely-guarded recipes, temporarily forgot how a certain dish was prepared. She asked her Creole cook, whom she herself had taught, for the recipe. The cook wouldn’t give it back.

Still highly revered, recipes in the South are no longer quite so literally guarded. Generosity has touched the art of cooking, and now and then, it is said, a Southern lady will give another Southern lady her favorite recipe and even include all the ingredients, down to that magical little touch that makes all the difference.

In the following recipes, gleaned from ante-bellum homes in various parts of Mississippi, nothing is held back. That is guaranteed. Yankees are welcome to make these dishes. Follow the directions and success is assured.

Port Gibson, Mississippi, which General Grant on one occasion declared was “too beautiful to burn,” is the source of a group of noble old recipes. “Too beautiful to burn” by far are the jellied apples which Mrs. Herschel D. Brownlee makes and the recipe for which she parts with as follows:

JELLIED APPLESPare and core one dozen apples of a variety which will jell successfully. Winesap and Jonathan are both good.

To each dozen apples moisten well two and one-half cups of sugar. Allow this to boil for about five minutes. Then immerse apples in this syrup, allowing plenty of room about each apple. Add the juice of one-half lemon, cover closely, and allow to cook slowly until apples appear somewhat clear. Close watching and frequent turning is necessary to prevent them from falling apart.

Remove from stove and fill centers with a mixture of chopped raisins, pecans, and crystallized ginger, the latter adding very much to the flavor of the finished dish. Sprinkle each apple with granulated sugar and baste several times with the thickening syrup, then place in a 350-degree oven to glaze without cover on vessel. Baste several times during this last process.

Mrs. Brownlee stuffs eggs with spinach and serves with a special sauce, the effect of which is amazingly good. Here is the secret revealed:

STUFFED EGGS12 eggs

1 lb. can of spinach or equal amount of fresh spinach

1 small onion, cut fine

salt and pepper to taste

juice of 1 lemon or ½ cup vinegar

½ cup melted butter or oil

1 large can mushroom soup

1 lb. can of spinach or equal amount of fresh spinach

1 small onion, cut fine

salt and pepper to taste

juice of 1 lemon or ½ cup vinegar

½ cup melted butter or oil

1 large can mushroom soup

Boil eggs hard, peel, and cut lengthwise. Mash yolks fine. Add butter, seasoning, and spinach. Stuff each half egg, press together, and pour over them mushroom soup thickened with cornstarch, and chopped pimento for color.

Last of all, Mrs. Brownlee gives us this old recipe for lye hominy, which will awaken many a fond memory in the hearts of expatriate Southerners living far, far away.

LYE HOMINY1 gallon shelled corn

½ quart oak ashes

salt to taste

½ quart oak ashes

salt to taste

Boil corn about three hours, or until the husk comes off, with oak ashes which must be tied in a bag—a small sugar sack will answer. Then wash in three waters. Cook a second time about four hours, or until tender.

—An all day job: adds Mrs. Brownlee.

One of the things Southerners do on plantations is give big barbecues. For miles around, “Alinda Gables,” a plantation in the Delta near Greenwood, is right well spoken of for its barbecued chicken and spare ribs.

Mr. and Mrs. Allen Hobbs, of “Alinda Gables,” here tell you what to do with every three-pound chicken you mean to barbecue:

BARBECUE SAUCE1 pint Wesson oil

2 pounds butter

5 bottles barbecue sauce (3½ ounce bottles)

½ pint vinegar

1 cup lemon juice

2 bottles tomato catsup (14 ounce bottles)

1 bottle Worcestershire sauce (10 ounce bottles)

1 tablespoon Tabasco sauce

2 buttons garlic, chopped fine

salt and pepper to taste

2 pounds butter

5 bottles barbecue sauce (3½ ounce bottles)

½ pint vinegar

1 cup lemon juice

2 bottles tomato catsup (14 ounce bottles)

1 bottle Worcestershire sauce (10 ounce bottles)

1 tablespoon Tabasco sauce

2 buttons garlic, chopped fine

salt and pepper to taste

This will barbecue eight chickens weighing from 2½ to 3 pounds. In barbecuing, says Mrs. Hobbs, keep a slow fire and have live coals to add during the process of cooking, which takes about two hours. The secret lies in the slow cooking and the constant mopping of the meat with the sauce. Keep the chickens wet at all times and turn often. If hotter sauce is desired, add red pepper and more Tabasco sauce.

Mrs. James Milton Acker, whose home, “The Magnolias,” in north Mississippi is equally famous for barbecue parties under the magnificent magnolia trees on the lawn, gives a recipe which is simpler and equally delightful:

Heat together: 4 ounces vinegar, 14 ounces catsup, 3 ounces Worcestershire sauce, the juice of 1 lemon, 2 tablespoons salt, red and black pepper to taste, and 4 ounces butter. Baste the meat constantly while cooking.

P

ass Christian, Mississippi, an ancient resort where the most brilliant society of the eighteenth century used to gather during the season, is awakened each morning by the familiar cry, “Oyster ma-an from Pass Christi-a-an!” It would take everything the oyster man had to prepare this seafood gumbo as the chef at Inn-by-the-Sea, Pass Christian, orders it:

SEAFOOD GUMBOass Christian, Mississippi, an ancient resort where the most brilliant society of the eighteenth century used to gather during the season, is awakened each morning by the familiar cry, “Oyster ma-an from Pass Christi-a-an!” It would take everything the oyster man had to prepare this seafood gumbo as the chef at Inn-by-the-Sea, Pass Christian, orders it:

2 quarts okra, sliced

2 large green peppers

1 large stalk celery

6 medium sized onions

1 bunch parsley

½ quart diced ham

2 cans #2 tomatoes

2 cans tomato paste

3 pounds cleaned shrimp

2 dozen hard crabs, cleaned and broken into bits

100 oysters and juice

½ cup bacon drippings

1 cup flour

small bundle of bay leaf and thyme

salt and pepper to taste

1 teaspoon Lea & Perrins Sauce

1½ gallons chicken or ham stock

2 large green peppers

1 large stalk celery

6 medium sized onions

1 bunch parsley

½ quart diced ham

2 cans #2 tomatoes

2 cans tomato paste

3 pounds cleaned shrimp

2 dozen hard crabs, cleaned and broken into bits

100 oysters and juice

½ cup bacon drippings

1 cup flour

small bundle of bay leaf and thyme

salt and pepper to taste

1 teaspoon Lea & Perrins Sauce

1½ gallons chicken or ham stock

Put ham in pot and smother until done. Then add sliced okra, and also celery, peppers, onions, and parsley all ground together. Cover and cook until well done. Then add tomatoes and tomato paste.

Next put in the shrimp, crabs, crab meat and oysters. Make brown roux of bacon dripping and flour and add to the above. Add the soup stock, and throw into pot bay leaves and thyme, salt and pepper, and Lea & Perrins Sauce.

This makes three gallons of gumbo. Add one tablespoon of steamed rice to each serving.

The chef at Inn-by-the-Sea fries his chickens deliciously too. He uses pound or pound-and-a-half size fowls. Dressed and drawn, they are cut into halves and dipped into batter made of one egg slightly beaten to which one cup of sweet milk has been added, as well as salt and pepper. The halves of chicken are dipped and thoroughly wetted in the batter and then dredged well in dry, plain flour. The chef fries the chicken in deep hot fat until they are well done and a golden brown. He says be careful not to fry too fast.

Two other seafood recipes from the Mississippi Coast come out of Biloxi, that cosmopolitan city that began back in 1669, and where even today the European custom of blessing the fleet at the opening of the shrimp season is ceremoniously observed. “Fish court bouillon” is a magical name on the Coast, it is spoken in soft voice by the diner, the waiter, and the chef alike; its recipe should be accorded the highest respect; it should be made up to the letter, and without delay:

FISH COURT BOUILLON5 or 6 onions

1 bunch parsley

2 or 4 pieces celery

4 pieces garlic

6 small cans tomatoes

1 or 2 bay leaves

hot peppers to taste

1 bunch parsley

2 or 4 pieces celery

4 pieces garlic

6 small cans tomatoes

1 or 2 bay leaves

hot peppers to taste

Cut up fine, fry brown, and let simmer for about an hour, slowly. Prepare the fish, and put into the gravy. Do not stir. Cook until fish is done.

This will serve 8 to 10 people; for 10 or more double the ingredients.

To prepare fish, fry without cornmeal, and put in a plate or pan. Pour a portion of the gravy over it, and let it set for a while. Just before serving, pour the rest of the hot gravy over the fish.

Another valuable Coast recipe which comes from Biloxi is that for Okra Gumbo.

OKRA GUMBO2 or 3 onions

½ bunch parsley

5 or 6 pieces celery

1 small piece garlic

4 cans of okra, or a dozen fresh pieces

1 can tomatoes

1 pound veal stew, or 1 slice raw ham

½ bunch parsley

5 or 6 pieces celery

1 small piece garlic

4 cans of okra, or a dozen fresh pieces

1 can tomatoes

1 pound veal stew, or 1 slice raw ham

Cut all ingredients in small pieces and fry brown. Let simmer for a while. If shrimp are desired, pick and par-boil them and add to the ingredients the shrimp and the water in which they were boiled. If oysters or crab meat is desired, add to gumbo about twenty minutes before done.

Add as much water as desired.

Aberdeen, Mississippi, is a good Southern town to find recipes. Old plantations along the Tombigbee River centered their social life in Aberdeen as far back as the 1840’s, and some of the recipes that were used in those days are still being made up in this part of the country.

Mrs. C. L. Lubb, of Aberdeen, uses this recipe for beaten biscuit.

BEATEN BISCUIT4 cups flour, measured before sifting

¾ cup lard

1 teaspoon salt

4 teaspoons sugar

enough ice water and milk to make a stiff dough (about ½ cup)

¾ cup lard

1 teaspoon salt

4 teaspoons sugar

enough ice water and milk to make a stiff dough (about ½ cup)

Break 150 times until the dough pops. Roll out and cut, and prick with a fork. Bake in a 400-degree oven. When biscuits are a light brown, turn off the heat and leave them in the oven with the door open until they sink well, to make them done in the middle.

Other books

Highlander’s Curse by Melissa Mayhue

The Professor by Cathy Perkins

The Streetbird by Janwillem Van De Wetering

Cosmocopia by Paul Di Filippo

Bloody Williamson by Paul M. Angle

Redemption by Eleri Stone

Shallow Creek by Alistair McIntyre

The Forbidden Script by Richard Brockwell

French Lessons: A Memoir by Alice Kaplan

The Forsaken by Lisa M. Stasse