The Forever Hero (39 page)

Authors: Jr. L. E. Modesitt

The newborn had only cried once, enough to clear his lungs, and, placed on his mother's stomach, had immediately tried to go to her breast.

Both the mother and the nursing tech pushed him gently into position, somewhat awkwardly because neither had much experience in the matter.

The I.S.S. surgeon completed her work, focused on the sterilizers, and gave the mother a quick jolt from the regen/stim tube, all according to the tapes she had studied and studied for the past week.

The infant resisted when the surgeon lifted him away from his mother for the prescribed checks, reflexesârespiratory and neuralâbut did not cry, though his eyes were wide.

His look bothered the surgeon, but she completed the checks as surely as she could, and returned him to his mother's breast. Then she entered the results on the health chart, a standard Service chart suitably modified for the newborn, whose reflexes had topped the scale, and who plussed the green for neural potential.

Dr. Kristera repressed a sigh. Standora wasn't the best place for a newborn, not with the background contaminants from the facility, and not with the lack of dependent care facilities.

The mother, stretched out on the light-grav stretcher, cradled the tiny boy at her breast with her right arm.

The doctor could see the sucking movements, and both the gratitude and tiredness on the mother's face.

“Why?” murmured the surgeon to herself. To have had the child could not have been a spur of the moment decision, not when having a child had to have been a positive choice before the fact. And the interruption in the young lieutenant's career as an I.S.S. pilot wouldn't help her promotion opportunities, since it would be more than a year before she could leave detached duty for accel/decel related duties

âif

she chose to stay in Service and if she chose to leave the child.

The I.S.S. surgeon looked again. Carefully, she approached the mother and child. “How do you feel?”

“Tired. Tired.” Her smile was wan. “But glad.”

“How's your friend?”

“Hungry.”

The surgeon bent down, trying to get a better look at the boy's eyes, which opened for a moment, as if the newborn had sensed her approach.

The baby's eyes were not blue, but yellow-flecked green, a strong color intensified by the short blond fuzz that would become hair. Dr. Kristera had to stop herself from pulling away from the intensity of the newborn's look.

“He'sâ¦strongâ¦,” she temporized to the mother.

The pilot nodded, closing her eyes.

The surgeon straightened and took the mother's pulse. Strong. The pilot was in excellent condition, had kept in shape, obviously, even though the birth had cost her more than any single high gee maneuver in the operations manual.

The surgeon stepped back as the nursing tech returned.

Maintenance stations were not equipped for childbirth, and for some reason the mother had rejected adamantly the local civilian health care. The C.O. had granted her request to use base facilities.

The surgeon wondered if his permission were yet another part of his efforts at upgrading Standora. Already, the load on the docks was increasing, after decades of neglect.

“You can go now, doctor,” suggested the nursing tech, a stocky mid-aged woman.

The I.S.S. surgeon nodded and turned, worrying at her upper lip with her lower.

What was it about the child?

The blond hair was uncommon at birth, but certainly not rare. But the eyesâ¦it had to be the eyes.

She wished she had more background for O.B. work, but who expected much in the Service, particularly away from the main staging and training centers?

All babies had blue eyes at birth. Or dark ones. Didn't they?

Who had eyes like that? Like a hawk?

She sucked in her breath.

“It couldn't beâ¦it couldn't⦔

She remembered who had eyes like a hawk, eyes that missed nothing. How could she have forgotten? How could she have possibly forgotten? Was that why he had given his permission?

Mechanically, Dr. Kristera began to peel off her gloves. She shook her head.

Who ever would have thought it?

Shaking her head slowly, she began to remove the rest of her operating room clothing.

Screeeâ¦thud!

The mass of metal that had once been a pre-Federation scout came to rest in the makeshift cradle in the middle of the small hangar.

The man in the gray technician's suit, a repair suit without decoration or insignia, watched as the salvage trac eased back out into the gray morning. His hawk-yellow eyes scanned the black plates and fifty meter plus length of obsolete aerodynamic lines.

The pre-Federation scouts had been a good thirty percent longer and more massive than present scouts, with the attendant power consumption, but they had one impressive advantage from his point of view. They had been true scouts, able to set down and lift from virtually any world within thirty percent of T-type parameters.

Not that the jumble of metal, broken electronics, and missing equipment before him was really a scout. But it had been, and would be again.

“You MacGregor?” asked the trac operator, who had returned with the clipack after stopping the salvage trac outside on the tarmac. The shuttle port outside the hangar door served the few commercial interests of Standora and the small amount of native travel.

“Same.”

“Need some authentication.”

“Stet.” The man in the technician's repair suit produced an oblong card.

The trac operator inserted the card in her clipack, which blinked amber, then green.

“That's it.” The salvage operator glanced over at the long black shape and shook her head. “What you going to do, break it down for higher value scrap?”

“Client wants her restored.”

“Restored? That'd take years, thousands of creds.”

“You're right.”

“Why? No resale. Black hole for power use. Wrong construction for a yacht.”

“Prospecting.”

“If you say so.”

The salvage operator was still shaking her head as she left the hangar for her cab.

The technician, who was not exactly a technician, cranked down the hangar door. At one time, when Standora had been on more heavily traveled Imperial trade corridors, before the increasing power consumption of the newly colonized planets had pushed jumptravel for commercial purposes into fewer and fewer ships and trips, all the hangars had possessed luxuries such as individual conditioning units and powered doors. As the commercial travel had dropped, so had the amenities.

The long-term lease on the hangar barely covered the taxes and expenses to the owner, but the lease terms provided that any upgrades in the facility would revert to the owner at the end of the twenty year contract.

According to the logs that had accompanied the mass of metal that had once been a scout, the official name of the craft had been the

Farflung

.

While the hull contained the fragments of drives, generators for screens and gravfields, all the communications gear and the minimal weaponry associated with scouts had been removed before the auction. That was fine with him, since weaponry mounted for use was illegal and since he intended to use the equivalent of equipment associated with more impressive craft.

He laughed once as he turned back toward the graving cradle. The power consumption from what he planned for the main drives and screens would really have stunned the salvage operator.

As she said, it would take time.

But timeâ¦that he still had.

Timeâwhile the devilkids struggled half a sector away at the mechanically impossible task of restoring Old Earth. Timeâwhile Eye and Service headquarters watched him and wondered how soon he would begin to age and die. Timeâwhile the ghosts of Caroljoy and Martin nibbled at the warmth provided by Allison and Corson.

Yes. He had time. For now.

His steps were measured as he came through the stone archway. His black boots, not quite polished to the sheen expected of the Imperial Marine he was not, barely sounded on the stone steps of the rear entrance to the quarters.

“Good evening, Commander.” Ramieres nodded at the senior officer respectfully, but did not leave the cooktop.

Gerswin sniffed lightly, appreciating the delicate odor of the scampig. “Evening, Ramieres. Smells good. As usual.”

“Thank you, Commander. I do my best.”

The commander smiled. The rating was the best Service cook he had run across in his entire career, and better than a score of the so-called chefs whose dishes he had sampled over the years.

He knew he would miss Ramieres when the younger man finished his tour in less than three months.

“How long before dinner's ready?”

“For the best results, I'd rather not hold it more than another thirty minutes, ser.”

“Try to make it before that. See how the upstairs crew is doing.”

Ramieres did not comment, instead merely nodded before returning his full attention to the range of dishes and ingredients before him.

Gerswin swung out of the huge kitchen through the formal pantry and took the wide steps of the grand staircase two at a time.

From the faint scent of perfume to the additional humidity in the upstairs hall, he could tell that Allison had just gotten out of the antique fresher that resembled a shower more than a cleaner.

She was sitting in the rocking chairâanother antique that he had found and refinished for herâwith Corson at her breast. His son's eyes widened at the sound of the door and his footsteps, but the three month old did not stop his suckling.

Allison wore a soft purple robe that complimented her fair complexion and blonde hair.

“Interrupted your dressing?”

She nodded with a faint smile. “I always dress for dinner like this.”

Grinning back at her, he sat on the side of the bed next to the chair.

“Are you going to stay home tonight? Or go out and play with your new toy?” Her voice was gentle.

He forced the grin to stay in place. “Thought I'd spend the time with you and Corson.”

“That would be nice. He's had a late nap, and I think that he will have to have dinner with us.”

“He about done?”

“In a minute. He's like you. There's not much in between. When he's hungry, he's hungry. And when he's not, he's ready to tackle the world.” Allison brushed a strand of long hair back over her left ear.

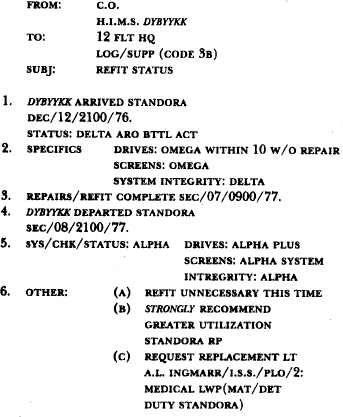

Since she was no longer on high-acceleration duty, she had let her hair grow far longer than when they had met, during the refit of the

Dybyykk

.

He watched as her eyes studied the greedy man-child as he fed.

“Hungry?”

“I am. He eats so much that I can eat just about anything.”

“Corson?” he asked quietly.

She laughed a soft laugh. “Why ask? You know he's always hungry, the greedy little pig.” She paused. “Like his father.”

Gerswin quirked his lips.

Abruptly the baby's mouth left his mother's nipple. He turned his head and eyes toward Gerswin.

“See? When he's done, he's done.”

The mother, who had been and remained an I.S.S. pilot, swung her son onto her shoulder and began to pat his back gently.

“I'll do that. You get dressed.”

“You don't want me dining in my finery here?”

“You'd shock Ramieres.”

“I doubt that. The fact that you might let me appear in anything this revealing might shock him.”

Gerswin leaned forward and extended his arms.

In turn, edging forward from the rocking chair, Allison eased Corson into his father's arms.

The commander stood and inched the boy baby farther up onto his left shoulder, holding him in place with his left hand and patting his back with his right hand.

A gentle “

brrrp

” rewarded his efforts.

“You do that so easily. It amazes me that he's your first.”

Gerswin did not make the correction. He had never held Martin, had never even known Martin had existed until well after his first son's death. And perhaps he had had other sons or daughtersâthat was not impossible, although he did not know of any.

His lips tightened, and he was glad he was looking out the window, facing away from Allison.

How would he know? Much as he attracted women, he also drove them away. How would Allison feel two months, two years from now?

Gerswin repressed a shiver. She had already picked up that he had intended to work on the old scout after dinner. Nowâ¦how could he?

She had obviously come back to the quarters after a full day in the operations office, determined to look good for him and to spend the time with both Corson and him. So how could he leave?

He forced his face to relax as he turned toward the dressing area where Allison was pulling on a long and decidedly nonuniform lowcut gown.

He could feel Corson's fingers digging into his shoulder, could feel the small body's heat against his, and the smoothness of his son's skin as he bent his head to let his cheek rest against Corson's.

Gerswin let the sigh come out gently, silently enough that Allison would not hear.

“How do I look?”

“Exquisite.”

She frowned. “You make me sound like a piece of rare porcelain.”

“Not what I had in mind.” He grinned, not having to force the expression as much as he feared.

“I know what you had in mind. But I'm hungry, and Corson won't be sleepy until after dinner.

Well

after dinner.”

“Then we shouldn't keep Ramieres waiting.”

“No. Not tonight, at least.”

Gerswin ignored the hint of bitterness and reached out to brush his fingertips across Allison's cheek.

She grasped them, pressed them to her lips, and smiled her soft smile.

“Shall we go, Commander dear?”

He nodded, and the three of them made their way down the grand staircase toward the dining room, which would dwarf them.