The Forgiven (20 page)

Authors: Lawrence Osborne

Thirteen

Thirteen

S THE TOYOTA ROLLED DOWN THE HILL TOWARD THE

S THE TOYOTA ROLLED DOWN THE HILL TOWARD THE

road, the tall Kebbash who had opened the door for him leaned forward and asked David in perfect French, almost unaccented, and with a distinct politeness, if he would like a cigarette for the road. The old man, he said gaily, always insisted on driving and, by God, he could not be dissuaded from this sad duty, though it was unendurable for all concerned. David reluctantly accepted the cigarette, though he disapproved of the habit, naturally. But now, he reasoned, it would help him get through the hours. He therefore took the crumpled Gitane without a word and let the man, Anouar, light it for him. Their eyes met and they did not duel. Anouar seemed quite courteous and intelligent. There was something boyish and calm in his manner and voice, a lilt and a skip and a small murderous humor. He talked with his head on his side, like a large inquisitive parrot. “Your wife,” he said sincerely,

“is very pretty. I will one day have a

gazelle

like that, God willing.” But would He be willing?

All six men were smoking by the time the car bumped its way onto the road, which was plunged in porous darkness and empty of traffic. They tore along it at a clip nearing eighty miles an hour, the wheels whining loudly, the windows vibrating as the nuts and screws shook. The engine shuddered. To David, the road suddenly looked like something intimately known. The white box-shaped guardhouses standing next to ditches and the straggling thorn trees were burned into his recent memory. Only the slopes of loose rocks looked higher than they had, less regular, and between them the groovelike ravines where the darkness seemed to collect like a fluid. It was now heavy in some way, this landscape, ominously saturated with its own inner gravity. Bones, marrow, but no skin, no external sheen.

Abdellah drove with his foot rammed into the accelerator and nothing else. He looked at the road and never at David. The men said nothing except when the cigarettes were lit. Only Anouar leaned forward to say a few things close to David’s ear.

“We are driving straight through. We will stop in Erfoud to see some people and have a drink. And a nap.”

Before long they passed into the outskirts of Errachidia. The city rectilinear, with wide avenues thronged with thousands of male students, and a soft light covering it, turning everything a dark gold. They shot over a bridge spanning a surprising river, the waters lit up by rows of lamps, and then rumbled along the flat, hard boulevards of what had once been a French military town. The buildings were uniformly white and so were the robes and hats of the innumerable students. There was still something of the desert barracks about the place, the departed Foreign Legion, and in the great spaces between the apartment blocks, one could see—or sense—the flat line of the desert that was close enough to smell. There was no trash, and no animals—perhaps the seasonal heat had burned them away—and the young men thronged there in small clusters seemed scrubbed and neat,

without animality themselves. It was an optical illusion. The outside never knows anything.

They stopped at a street corner to buy Cokes and sandwiches. David got out to stretch his legs. The air was so hot that his face winced despite his own determination not to betray any discomfort in front of his “captors.” It was a struggle. Sand bit into his nostrils. Anouar asked him if he wanted to pee and he shook his head. It was impossible to tell what time it was, and through some vague superstition, he didn’t want to glance at his watch. Instead he watched Abdellah kneel by the wheels of the Toyota and inspect the tires. Under the orange lamps, he looked more youthful, more lithely menacing. He clucked and said nothing to anyone, and his filthy shoes, David noted, had small cheap gold chains on them. The other men, moreover, seemed awkward around Abdellah, as if the embarrassment caused by his bereavement could not be lightened by the usual bonhomie. They did what he asked, and they did it quickly.

ON THE FAR SIDE OF ERRACHIDIA, THE ROAD NARROWED

and sand drifted across it; low mud walls sometimes hemmed it in, and behind the walls rose the dark cool of palmeries tossing in the wind. Men with agonized blank faces trudged by the roadside with gaggles of goats, and their eyes flashed like cats’ as they looked up into the headlights and didn’t blink.

David watched the faces of the Kebbash in the rearview mirror. They were chewing dates now, passing around a piece of sticky paper, though not to him. Perhaps they assumed that it would be offensive to his tastes. The pace slowed as the road became smaller and more cracked, and the father at some point reached down and switched on the car radio. The men sighed, affected by a burst of religious music. David struggled to keep awake, exhausted emotionally by the evening’s events, and his hand gripped the shattered metal window handle. He reflected that none of the other men had been introduced

to him, or their names divulged. It suggested that now names didn’t matter much, because he was not an ordinary guest. Crammed together uncomfortably, they stoically endured the ride until one of them leaned down and picked up something heavy and metallic, and from the corner of his eye he sensed the presence of an old rifle. But it was not directed toward him. It was raised against the outside environment, which seemed to make them anxious as the palm groves thickened and the desert plains made themselves felt on either side of a road that relentlessly narrowed and became more suffocating. They were, he said, nearing Erfoud, inside the Tafilalet, the largest oasis in North Africa. From here came the royal family of Morocco.

David finally did glance at his watch. It was almost midnight. His mind was shrieking silently, and his sweaty hand let go of the handle. Abdellah huffed.

“He says we’ll go to the hotel,” Anouar translated from the backseat. “No one can drive across to Alnif in the dark.”

What he added in French was

“On regrette.”

But what did they regret?

“What hotel are we going to?” David asked pitifully.

“It’s the hotel where the fossil dealers go. The Hotel Tafilalet.”

They passed along streets of rose-brown houses with yellow and turquoise shutters, blue grilles, and white crenellations along the roofs. Erfoud sat in its winds and dust, obstinate and sunken, and it was not even yet the sleeping hours. In the hot season, night was precious, a time in which to be alive and do one’s business. Horse-drawn carts clattered around them piled with alfalfa and mint, lightbulbs exploded into life out of the dark, out of the arcades of a market where the flies had died down. The sidewalks were long piles of rubble behind which people sat on mats, staring at the traffic like people who are expecting a downfall of volcanic ash that will bury them for centuries. There were the same fossil shops he had seen in Midelt. The same gaunt men with trays of shark teeth and lumps of crinoids, the same boys running alongside the cars shouting

“Dents de baleines!”

THE HOTEL TAFILALET STOOD ON ONE OF ERFOUD

’

S MAIN

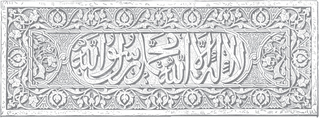

streets, of which there were two. It was done in the Arabian Nights style, green and blue, with kitschy

mihrabs

, columns, and alcoves that made its lobby seem denser and more majestic than it actually was. It looked like a smoker’s den in a private club, with water pipes set up next to the tables and forms cradled inside cushioned benches.

Around the pool, a few outdoor tables were set with sheltered candles, and here knots of men sat with their beers and smokes trying to find some relief from the scorching winds that rippled the water. The Kebbash parked the Toyota in the hotel lot and left two of the men to guard it; Abdellah strode through the lobby as if it were his living room, as if his physical shabbiness didn’t matter there, and David came behind him, egged on by Anouar. They passed a bar next to the pool, its stone surface encrusted with ammonites. A few aghast-looking Europeans sat there, not knowing what to do, since it was too hot even to go in the pool, and their blue eyes watched the group shuffle into the garden and settle at a table where they ordered cold sodas for themselves, then in a comical pantomime settled David at a table all by himself.

“They will bring you a cold soda,” Anouar explained. “There is a room upstairs where you can sleep. We get up again at five. I will come for you.”

“But why am I by myself?”

“It is more fitting, that’s all. Surely you understand?”

He did understand; in fact, he preferred it. His exhaustion overcame him and he slumped onto the table, his eyes ready to close. He gulped down the 7-Up in its glass of crushed ice, then tried to steady his nerves. The pool was surrounded by tall palms planted on the far side of the walls, and their bushy heads tossed in the gusts. The light was brown with flying sand, like the inside of an old fish tank. The grit didn’t seem to bother the locals, who obviously came here to network and trade. Mostly fossil dealers, he imagined, they floated about from

table to table with elaborate gestures of friendship and small trays of polished ammonites. Did they, too, believe that these creatures were small demons who had fallen from the skies long ago? As they bowed at each table, they touched their chests with one hand and adopted a pleading tone. To David, they were especially pleading.

“Monsieur, Monsieur, des très beaux ammonites de Hmor Lagdad! Des purs, des rares! Regardez, et pour vous, Monsieur, un prix étonnant, ridicule!”

As they pressed desperately upon him, the Kebbash looked over with great amusement. The manager of the hotel had come out to greet them quickly, and the Erfoud dealers also passed by to shake their hands. The men from Tafal’aalt were key suppliers.

David shooed the sellers away irritably. He called Jo on his cell but there was no signal. He cursed under his breath and considered asking the manager if there was e-mail at the hotel. But when the manager came over, David had nothing to say. Suave and multilingual in the Moroccan way, the manager preempted him in impeccable, singsong English.

“Do not believe those sellers,” he laughed, gesturing toward virtually everyone there. “They are all liars. But if you would like to support their families, it is a good thing to do. One fossil feeds a child for a month.”

“I wouldn’t know what to buy,” David said bluntly.

“I would recommend a trilobite called a Spiny Phacops. All the tourists seem to love them. Especially the Belgians. However, I see that you are not Belgian. Nevertheless …”

David shook his head mournfully.

“A Spiny Phacops never disappoints,” the manager went on like a busy toy train. “Bill Gates loves them. Your wife will love them. I love them. Perhaps you will love them, too.”

“I’m not really in the mood.”

“

Awili achnou hadchi

. What the hell. As you wish. I am sending over something to eat, at the request of your hosts. A

tagine

, which is a special dish of the Tafilalet. Your room is ready when you want to sleep.”

He ate determinedly. An elderly Frenchwoman entered the pool, oblivious to the scornful men observing her, and swam mechanically up and down in a pair of goggles. It was amazing that people came here and stayed in the new five-star resorts lining the roads out of town. The desert was popular with package tours, but mostly they stayed safely near Erfoud. Who was this stubborn old bird doing her laps past midnight? It was probably too hot to sleep in the rooms. He tried to keep up an appearance of stoic English fortitude in front of the table of his captors—as he thought of them. He set his jaw and stared into space, even though his innards were dragging him down and he longed to be alone in that room upstairs. You can’t show fear or even discomfort in front of these people. You have to show indifference to both. You have to show disdain. Yet in the end, the most disconcerting thing was that the Kebbash didn’t even look at him at all. They ignored him completely. The old French lady shot him a quizzical, mystified look from the pool and he wondered if he should ask her for help. It would be a comical scene.