The Forgotten Children

Read The Forgotten Children Online

Authors: David Hill

During his remarkable career, David Hill has been chairman, then managing director, of the ABC, chairman of the Australian Football Association, chief executive of the State Rail Authority NSW, chairman of Railways of Australia and chairman of the CREATE Foundation – a national organisation working to improve the lives of young people and children in the care system. He lives in Sydney. This is his first book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Forgotten Children

ePub ISBN 9781742741925

Kindle ISBN 9781742741932

A William Heinemann book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney, NSW 2060

www.randomhouse.com.au

First published by Random House Australia in 2007

This edition published by William Heinemann in 2008

Copyright © David Hill 2007, 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the

Australian Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia.

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.com.au/offices

.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Hill, David, 1947–.

Forgotten children.

ISBN 978 1 74166 614 4 (pbk)

Hill, David, 1947 – Childhood and youth. Fairbridge Farm School (Molong, NSW) – History. Immigrant children – Australia – Biography. Immigrant children – Great Britain – Biography. Immigrant children – Institutional care – Australia.

304.894041092

Author photograph by Ian Bayliff

Cover design by saso content & design pty ltd

For Stergitsa and Damian

ONTENTS

There was rumour in the orphanage

For word had got around

That certain little inmates

Were soon Australia bound

With others, not so lonely

’Twas Government intent

They’d have a horse or pony

Like a little English gent

With a largish cardboard suitcase

Up the gangway walked with glee

The ship then headed seaward

Good bye to family

Six weeks long the journey

Where luxury did abound

But then the final landing

With feet on foreign ground

A long and tiring journey

Through country parched and dry

With ne’er a single hedgerow

’Neath a blazing sun and sky

In house with thirteen others

Who snored or cried all night

Just little English children

Too tired to snarl or fight

Then appeared the rosters

Apportioning the work

To scrub and clean and polish

No chance to ever shirk

To till the market garden

With shovel and with hoe

Planting lots of cabbages

And taters in their rows

Harnessing the draught horse

To the single furrow plough

Holding fast the jerking handles

To plough a straight furrow

Sitting on the bucking tractor

Sowing in the wheat

Smothered in both sweat and dust

From the never-ending heat

Training for the future

The farming life ahead

But surely little migrant lad

You should be in your bed

It’s fine to look so manly

With all your duties done

But little British orphan

Where has your childhood gone?

Len Cowne, March 1999

Len was in the first group of children to arrive at Fairbridge Farm School in Molong in 1938.

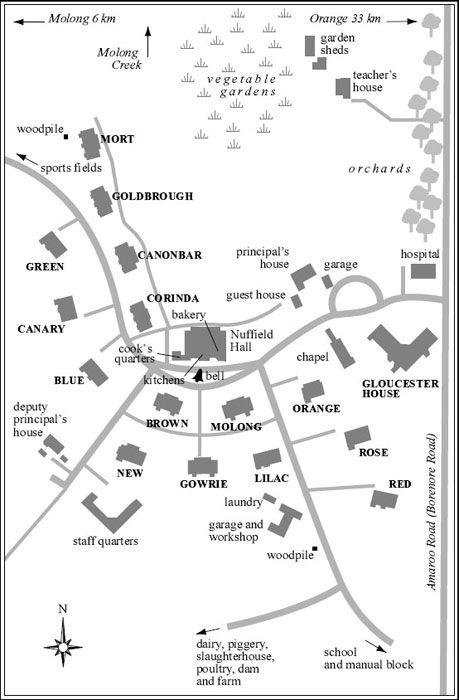

Plan of the Fairbridge Farm School Village

REFACE TO THIS

E

DITION

The publication of the book

The Forgotten Children

caused quite a stir in both Britain and Australia, where some of the revelations from hitherto secret files and from the stories of former Fairbridge children attracted widespread media coverage.

The Fairbridge Farm School Scheme was roundly applauded during the 70 years it sent impoverished British children to farm schools in Australia, Canada and Rhodesia. Fairbridge aimed to create worthy citizens for the British Empire by converting boys and girls from English city slums into farmers and farmers’ wives, and promised opportunities and an education that the children could not hope for if they stayed in England.

But for many of the child migrants, some as young as four years old and never to see their parents again, the story was very different. Many were denied the promise of a better future, and most were forced to leave school at 15 with no education to work full-time on the farm. The typical child experienced social isolation and emotional privation and spent his or her entire childhood without ever experiencing the love of a parent. When the young migrants left Fairbridge at seventeen years of age, they had nowhere to go and no one to go to. The Fairbridge files in both the UK and Australia that have never been made public show that Fairbridge failed in many of its aims and corroborate most of the experiences the former Fairbridge children relate in the book.

Since the book was released, more former Fairbridge children have come forward wanting to tell their stories. These include the allegation that Lord Slim sexually molested a number of the boys while visiting Fairbridge when he was the governor-general of Australia. Slim was a greatly respected and revered war hero, both in Australia and in Britain, who later became the chairman of the Fairbridge Society in the 1960s when he returned to live in England.

When I was researching the book, one of the former Fairbridge boys had told me that the then Sir William Slim had molested him and a number of others in the back of the governor-general’s chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. While I believed his story, the boy did not want the allegation recorded and was not prepared to publicly defend the claim, so I thought it was unfair at the time to include it in the book.

However, since then other boys have told newspapers in Britain and Australia that it also happened to them, including Robert Stephens, who happened to be at the Molong Fairbridge Farm School when I was there.

Robert says that he and a number of other boys of eleven and twelve years old were offered rides in the Rolls-Royce up and down the drive along the Amaroo Road between Fairbridge and the main road about one kilometre away. During the ride he was forced to sit on Slim’s knee as Slim slid his hand up inside Stephens’s shorts.

Other boys spoke of fondling in the back of cars as he toured the farm. How do you explain it? We were innocent kids. I guess we were vulnerable and in a position where no one could really speak out. No adult would believe these things happened, so you didn’t talk about it. You think you are the only one. Like so many things that happened at Fairbridge, they don’t go away. They live with you all your life.

Ron Simpson is now 78 years old and lives in Sydney. He came out to Australia and to Fairbridge in 1938 as a nine-year-old with his seven-year-old sister Mary and is another who now wants to tell what happened to him.

Ron recounts how his back was broken when he was beaten with a hockey stick because he was late getting in the cows for the early-morning milking when working as a trainee boy on the Fairbridge dairy:

It wasn’t even my fault. The cottage mother forgot to pull out the pin, so the alarm clock didn’t go off. The other boys woke me up, and there was a mad rush to get to the dairy and bring the cows in to milk. So we were very late and got down to breakfast at seven-twenty. Principal Woods came over and told me to see him after breakfast.

When I arrived at the principal’s house, I knocked on the door, and he said come in, and I had just stepped in, and he was there holding a hockey stick in his hand. He grabbed me by my shirt collar, pushed my shoulder down, then gave me a tremendous wallop across my lower back. I fell into a big black bath opposite the hallway, screaming in pain. He pulled me out of the bath, then he did the same again. This time I flew through the entrance door and hit every step on the way out.

Ron went back to work with constant and worsening back pain. A month or two later he was chopping wood for the village kitchen stoves when he collapsed and had to be carried in a wheelbarrow by another boy to the village hospital.

I was chopping wood, and as I stooped down to put it into the barrow I felt a terrible shooting pain from my lower back down my legs. I collapsed onto the ground and couldn’t move the lower part of my body. I felt no pain, but try as I might I could not stand. Another boy who was with me lifted me into the wood barrow and ran me down to the farm nurse. She put me into a bed and called for the doctor at Molong, who came and checked me out and said I’d be all right in a couple of days. The nurse treated my back with some liniment, and … they got me out of bed in three days, and I was in pain, and I couldn’t sit on my backside. I was sitting on my spine.

Back at work his condition worsened, and the pain continued until one day the local Molong vicar, who was visiting Fairbridge, noticed him crying in pain and unable to sit properly. The vicar asked to be able to take him to Orange Base Hospital. After some months he was transferred from there on a stretcher by train to Sydney Hospital.

Ron still has some of his old hospital records. For more than a year he lay in the hospital bed with sandbags supporting his back, and apart from being visited by Charlie Brown, a former Fairbridge boy who had joined the army, Ron doesn’t recall ever seeing his sister or any other Fairbridge children while he was there. Ron says he told anyone who asked how the injury had occurred, but no one followed it up with any further inquiry.

Eventually, when he was able to walk again, he was returned to Fairbridge and spent the next few years wearing a metal-framed brace around his torso that he only took off at night when he went to bed. After he left Fairbridge, he was found a job on a neighbouring property, and he remembers Fairbridge providing him with a new brace when the old one wore out.

More than 30 years later and after decades of back pain Ron received a message from another Old Fairbridgian that Woods, who was in retirement, was asking after him.

Tommy Cook, an Old Fairbridgian down at Dapto, saw Woods. Woods kept on asking for me and said, ‘If you see Ron Simpson, tell him to please come and see me.’ But I never did. I wouldn’t go and see him … Even just before he died, he asked to see me, but I wouldn’t go near the man. I didn’t go to his funeral either … I think he just felt guilty about what happened to me.

I just couldn’t go through and say, ‘It’s all right, mate.’ It’s been with me all these years, and it’s a dreadful thing to happen to anyone, to children.

Many of the children spent their entire childhood at Fairbridge with no one to turn to and feeling that no one cared anyway. But there were some good staff at Fairbridge who genuinely cared for the kids and who are still fondly remembered.

Following the publication of the book a man came forward to say that his mother had worked for Fairbridge in England and had for many years remained upset about what she saw.

We all knew her as Matron Guyler who ran the big Fairbridge house in Knockholt in Kent where we were all sent prior to being put on the ship to Australia. We all remember her filling our heads with exciting dreams of what Australia and Fairbridge would be like.

What we didn’t know is that she had never seen the place until she went to Australia on a visit in 1961 prior to her retirement. Apparently she was horrified with what she saw and protested, in vain, to the Fairbridge Society in England when she returned.

Her son Mike, who now lives in Australia, described his mother’s reaction to the visit in an email he sent to me after the book’s first publication:

My mother was horrified by what she saw at Molong, but really she only saw the surface. What she did see were cold, hungry, unhappy children. All the new clothes that they had when they left England were gone. The cottage was dirty and the cottage mother … defensive. The thing that most affected my mother was the look in one of the children’s eyes. I don’t know if it was a boy or a girl, but my mother told me that she never saw such a pleading look, and it went straight to her heart.

Michael was not a Fairbridge boy himself but he has been in touch with a number of Old Fairbridgians in recent years. He said his mother was now 98 years old ‘but still talks of her horror at what Fairbridge allowed to happen in Australia’. He said she was living in a nursing home near Epsom in England and asked if one of the former Fairbridge kids might be able to visit her to reassure her that it wasn’t her fault.

I wonder if there is any Fairbridge boy or girl who now lives near Epsom who might be able to visit her and tell her that she was not to blame. I know that she still feels betrayed by what she discovered. (She really has no idea of the full extent of what went on.) Her mind is still pretty good, and I think it would comfort her. Of course I am aware that there are many Fairbridge children for whom there is no comfort, and it troubles me that I have known many of the children who were subsequently beaten, starved, abused and denied love.

The Fairbridge organisations in both Britain and Australia still deny any failings of the Fairbridge scheme, as they did when giving evidence before parliamentary inquiries into child migration in both countries in 1998 and 2002.

A former Fairbridge girl, Claire B, now living back in England, said the book had prompted her to ask for her records from the UK Fairbridge office, where she was told

The Forgotten Children

‘was full of tales and lies told by small children’. In Sydney the Fairbridge Foundation said it still wanted proof of what went wrong at Molong, even though much of the evidence came from the files that remain in its Sydney office.

Some locals from the Molong district and even some former Fairbridge children were upset by the media coverage and reviews that followed the release of the book, and a number have been critical of what they perceived as the negative picture the book painted of Fairbridge. The strongest criticisms have come from those who are so upset or disgusted by the book that they have publicly declared their refusal to read it. The chairman of the Old Fairbridgians’ Association, John Harris, who was interviewed for the book, said he was ‘annoyed’ by the publication. ‘It will be everyone’s own decision whether they purchase the book, and in my case it will not happen,’ he said.

For many of the former Fairbridge children the recounting of their stories is the first time they have told anyone about their experiences. They have revealed in the book what they have been unable to tell even their loved ones and their families. I feared that some would be traumatised when they read about themselves for the first time, particularly about being sexually abused. However, most have said they have now been able to draw strength from reading that many other children at Fairbridge went through similar experiences.

And many of the families of the former Fairbridge children have said how they have found the book useful in understanding their parents. Many former child migrants never talk about what happened to them, which has left their families with little knowledge or understanding of their parents. ‘Thank you,’ said one woman. ‘I’ve never really liked my father, but now I can see why he is like that. I had no idea how much he suffered as a child.’

Now a number of former Fairbridge children have joined together and through the Australian law firm Slater & Gordon are taking action against Fairbridge. Most say that they are motivated not so much by the money but by a desire to see that the wrongs that were done to the children are at last acknowledged.