The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka (41 page)

Read The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka Online

Authors: Clare Wright

Tags: #HIS004000, #HIS054000, #HIS031000

In all likelihood, however, there was a ranking system, as has been documented on the American mining frontier, from high- to low-status prostitutes. The higher the grade, the more clandestine in soliciting custom, subtle about obtaining payment, likely to offer skills or talents besides just sex, and be involved with fewer and richer men. This sort of stratification also fits with what we know of the Ballarat goldfields, where competition for precious resources led to status rewards. Lucky men could afford to drink champagne, smoke cigars and hire attractive, gracious whores on a more or less permanent basis. Unlucky diggers were left to line up for the coarse, foul-mouthed tarts that hung about in the doorways of hotels and shanties. And some men couldn't even scrape together the two bits required to lay their burden down.

By the end of the winter of 1854, Ballarat was transformed. It was no longer a frontier outpost predicated on yanking nuggets of gold from the ground, but a fledgling town boasting

all the appliances of civilised lifeâ¦the comforts and conveniences of high civilisation

, as Thomas McCombie put it. The hotel. The store. The theatre. The printing press. McCombie crossed them off his list of heralds of progress. And they were institutions, McCombie failed to note, with women at the helm. Catherine Bentley and Mother Jamieson at the hotel. Tick. Martha Clendinning and Anne Diamond at the store. Tick. Sarah Hanmer at the theatre. Tick. Clara du Val Seekamp at the printing press with Ellen Young feeding her the copy. Tick.

The town was settling down. So why did no one feel at ease? Samuel Huyghue, high up on the hill, could see only a population

in a constant state of chronic irritation

. There they all were, scratching at an itch that would not subside, further inflaming the exquisite pain with every scrape of the flesh.

If, as Governor Hotham and James Bonwick believed, women were the ground order of society, and if they now controlled the instruments of civilisation in Ballarat, then the town should have been on the fast track to stability and regulation. But it wasn't. It was heading for a train wreck. And the women weren't hauling on the brake. They were stoking the coals.

Zealous diggers: mining as a family affair. S. T. Gill, 1852.

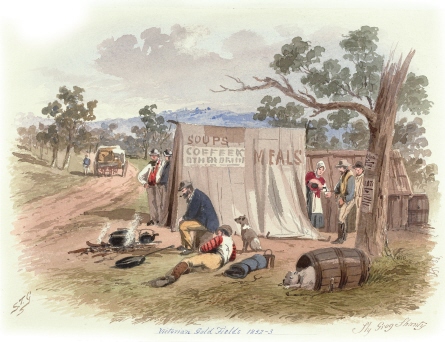

A ârefreshment tent' on the diggings. S. T. Gill, 1852â3.

Sarah Hanmer, probably c. 1860.

Interior of the Adelphi Hotel, with Sarah Hanmer on the right, 1854.

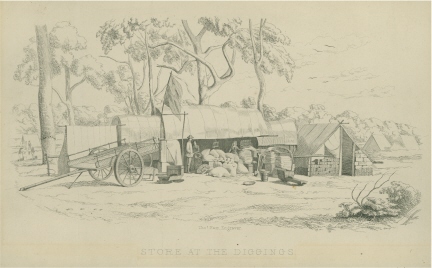

A store on the diggings, like the one Martha Clendinning would have kept. Thomas Ham, 1854.

Subscription ball in Ballarat. S. T. Gill, 1854.

âThe servant problem' as seen by

Melbourne Punch

, 1856.

Spring.

verb

move rapidly or suddenly from a constrained position.

noun

Â

1

the season after winter and before summer, in which vegetation begins to appear, in the northern hemisphere from March to May and in the southern hemisphere from September to November

.

Â

2

a resilient device, typically a helical metal coil, that can be pressed or pulled but returns to its former shape when released, used chiefly to exert constant tension or absorb movement.

They didn't call this Bentley's Hill for nothing. Catherine Bentley had a commanding view of the Ballarat diggings from the second-storey bedroom of her hotel. To the south, the vast sea of honeycombed earth stretching towards Red Hill and the Canadian Lead. To the northwest, the tent hamlet of Bakery Hill, where Clara Seekamp and her husband were churning out their newspaper. Stretched out along the Yarrowee River to the north, the golden gutters of the Gravel Pits Lead, and over the river, the old alluvial flats of Black Hill. To the east loomed Mt Warrenheip: grave, solid, like a conscience. To the southwest, she could see Golden Point. In one of those tents over there sat Ellen Young, scribbling the letters and poems that kept appearing in the

TIMES

.

This vast landscape of endeavour was now dry and thirsty. Spring had only just arrived and already the ground looked parched. A month ago, Catherine's lad Thomas was chipping ice from the water pail in the morning; now she would have to chase him to put his bonnet on. Come summer, she would have a new baby to shelter from Ballarat's inscrutable climate. A week of rain would put a stop to diggingâa busy week at the barâthen a week of hot winds would blow up clouds of dust. What a country, where things could turn around so just like that.

Beyond Bakery Hill, Catherine could see clear through to the Camp. The government men still did their drinking at Bath's Hotel, but by September 1854 she and James were raking in so much (£350 on their first night alone) that the toffs could go to hell anyway. She didn't need them in her front bar; they'd only scare off the locals. In any case, she and James would be in demand to attend to the next Subscription Ball; all the leading townsfolk were invited, especially if they had deep pockets. Even men like the Jewsâauctioneer Henry Harris and his mate Charles Dyteâwere always on the subscription list.

1

And now Harris and Ikey Dyte were storing their goods at her hotel. The merchant George Smith also entrusted over £300 worth of his wares to her care, including two dozen black satin neckties, five dozen fine linen shirts, three double-barrelled Dean and Adams revolvers, fifty-three gold signet rings, forty-four gold pencil cases and four dozen electroplated dessert spoons and forks. Smith even asked them to guard his Masonic certificate and apron.

2

Jacques Paltzer had been quick to sign up his band as the regular entertainment at Bentley's Eureka Hotel, especially since the band members could live upstairs. They were the most sought-after concert band on the goldfields and would no doubt be asked to play at the next ball. People might talk in envious whispers about what went on inside the big red house on the hill, but they wanted what the Bentleys had to offer regardless. Not just grog and cash, but the structure itself: the sense of permanence.