The Friar and the Cipher (23 page)

Yardley's group, whose funding came from the State Department as well as the army, was wildly successful, breaking the diplomatic codes not only of Japan, but of more than two dozen other nations as well, including Great Britain, France, and Italy. In 1929, the new secretary of state, Henry Stimson, upon discovering that America was spying on its allies, issued his famous (and astonishingly naive) pronouncement: “Gentlemen do not read each other's mail.” MI-8's funding was cut off and Yardley summarily dismissed.

Yardley was bitter, furious, and out of a job. There weren't too many places that an unemployed spy could offer his services, at least without committing treason. With the Depression eating away at his meager savings, Yardley sat down and wrote his memoirs. Published in 1931,

The American Black Chamber

was a record of his wartime activities but also revealed the extent of the United States' cryptanalytic work in the 1920s. At the time, there was no law against publishing such a book, and it caused the pedictable red faces at the State Department. Stimson was livid. (As a direct result, two years later, a law authorizing hefty jail terms for anyone betraying America's cryptologic activities was passed.)

With no legal recourse against Yardley, Stimson wrote his own book,

The Far Eastern Crisis

, in which he strongly suggested, among other things, that the Japanese revise their codes. The Japanese took the advice (although Yardley's revelations themselves would certainly have been enough) and were therefore able to communicate in secret in the days leading up to Pearl Harbor. Stimson, of course, later served as Franklin D. Roosevelt's secretary of war during the conflict with Japan.

Herbert O. Yardley exhibit at the National Cryptologic Museum

COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY

Yardley eventually worked for Chiang Kai-shek (and wrote another book,

The Chinese Black Chamber

) but was shunned by his native country until his death in 1958. He never took another shot at the Voynich manuscript.

MANLY'S CAREER TOOK A FAR DIFFERENT TURN.

Although he had been Yardley's subordinate, he was more than twenty years older and lacked both Yardley's intuition and charisma. But he brought to any task the painstaking thoroughness of the accomplished scholar. Three years after publishing his article in

Harper's

, Manly began a project sufficiently massive to be worthy of Roger Bacon himself. His goal was no less than to complete an authoritative compilation of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer with the aim of producing the definitive text of

The Canterbury Tales

. He recruited Edith Rickert, a former colleague at MI-8, into the English department and then set to work on a project that would occupy both of them for the rest of their lives.

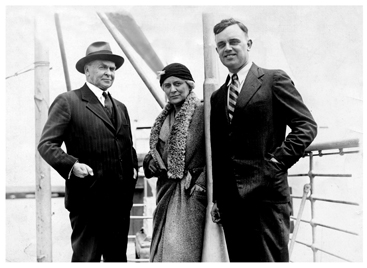

John M. Manly (

left

), Edith Rickert, and an assistant returning to America in 1932 after a summer spent in Britain on the Chaucer project

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LIBRARY

The Chaucer project is as fitting an example as one can find of the combination of intelligence, scholarship, doggedness, and endless immersion in detail that characterizes the elite cryptanalyst. What Manly had in mind was as bibliographic as scholastic, and he set up an academic version of MI-8 to do the job. According to the University of Chicago, the task included “collecting, photographing, and collating all existing Chaucer manuscripts and studying their provenance. A Chaucer textual laboratory was organized . . . where a team of graduate students meticulously analyzed photostatic copies of the eighty-three fragments and complete manuscripts of the

Tales

found by Manly and Rickert. Lettering styles, paper markings, and types of ink were examined to find clues that might help establish each manuscript's origin.”

Manly and Rickert stretched their personal finances to travel to Europe each year to visit museums, libraries, and private collections. They carefully examined manuscripts, searching for clues—any difference in the ink, paper, or binding might help differentiate a correct, early version of the text from a later imitation. Erasures were important, as was the manner in which the paper was trimmed. Provenance was vital, so they probed any surviving records concerning Chaucer's family or where he had lived for further clues.

The obsessive hunt for material began to wear down both Manly's and Rickert's health, as well as their finances. In fact, when Yardley came to Manly for a loan in early 1931, Manly was forced to turn his old friend down, after which Yardley immediately began his memoirs. Although Manly and Rickert completed what was to be the eight-volume

Text of the Canterbury Tales

, Rickert, exhausted, died in 1938, before the work was published. Manly died two years later, living just long enough to see his great effort in print. Both Manly and Rickert hold honored places in University of Chicago history, and there is now a John Matthews Manly distinguished service professorship at the university, which at one point was occupied by the great African-American historian John Hope Franklin.

One would think that while proceeding with such a single-minded effort even a scholar of Manly's capacity would have no time to revisit the Voynich manuscript.

But he did.

PROFESSOR NEWBOLD CONTINUED TO WORK

and transcribe according to his alphabet and anagrams, uncovering more and more of the marvelous legacy of Roger Bacon. Then, on the evening of September 25, 1926, he was struck with what the

New York Times

described as “acute indigestion.” The next day he was dead. His friend and colleague Roland Grubb Kent collated all of Newbold's transcriptions, notes, and papers on the Voynich manuscript and published them in 1928 as

The Cipher of Roger Bacon

.

Bacon remained largely unchallenged as a great mind of science who was centuries before his time. Thorndike continued to grumble—he wrote in 1929 in

American Historical Review,

“There is hardly one chance in fifty that Roger Bacon had any connection to the production of the Voynich manuscript”—but the fascination of the cipher was irresistible, and naysayers were dismissed with a wave of sour grapes.

Wilfrid Voynich died in March 1930. In his will, he named a panel of five experts, led by his “associate” Anne Nill, to sell the manuscript to an appropriate—and wealthy—public institution. (There is no specific evidence of how far this association went, but Voynich and Nill spent lots of time together, even taking sea voyages on which his wife, Ethel, was not present. Recently, a rumor has surfaced that Ms. Nill was the Voynichs' adopted daughter, but, as with almost everything else having to do with this manuscript, nothing is certain.)

Another member of the panel was Manly. That he stipulated that each of the five receive $3,000 (in 1930 dollars) for their time and effort is an indication of what Voynich expected the manuscript to sell for. Newbold's widow was to receive ten percent of the proceeds, Roland Grubb Kent another five percent. The remainder Ethel and Anne Nill would split sixty-forty.

Before it was actually sold, however, one of the five experts did something that was to vastly affect the selling price and the ultimate destination of the manuscript. In 1931, a forty-seven-page article appeared in

Speculum,

a journal published by the Mediaeval Academy of America. Its title was “Roger Bacon and the Voynich MS,” and the author was John Matthews Manly.

In the article, Manly revealed that Newbold had been sending him progress reports until his death, and, he wrote, “I told Professor Newbold of my conclusions and gave my reasons for them in several letters.” After Newbold's death, he had hoped to “let the subject rest,” but too many members of the scientific community had accepted the transcription and Manly felt forced to reexamine the issue in “the interests of scientific truth.” He did not mention in the article that a university, private library, or government agency was about to spend possibly a million dollars for it.

Then, with obvious sadness and reluctance, Manly proceeded to demolish the work of his friend, brick by brick, argument by argument. “In my opinion,” he began, “the Newbold claims are entirely baseless and should be definitely and absolutely rejected.”

Manly's objections were so fundamental that after reading his article, those who had accepted Newbold's claims could not believe they had done so. Anagramming, for one thing, was so subjective that even Newbold himself had come up with three distinct decipherments from the same passage. (The letters l-i-v-e, for example, can yield five distinct words, and the number of possibilities increases exponentially as more letters are added to the base.

*6

)

There were other obvious errors. In one case, Newbold copied the ciphertext incorrectly and then came up with a deciphered version anyway; in another he came up with a Baconian transcription from a passage that had not been part of the original manuscript but had been added later. As for the “shorthand,” the seeming separation of letters into strokes was merely a result of uneven paper texture and the ink line breaking over the centuries. Some of the history was wrong as well. According to Manly, an authority on the period, there were no “knights” at Oxford in 1273, and therefore the account of the riots was obviously wrong.

But what of Newbold's claim that he knew nothing of any of these phenomena before transcribing the cipher? For this, Manly had saved his most devastating assessment. Newbold

must

have known, Manly concluded, even if he was unaware of his knowledge, and therefore “his decipherments were not discoveries of secrets hidden by Roger Bacon but the products of his own intense enthusiasm and his learned and ingenious subconsciousness.”

Manly tried to lessen the blow in the end by stating that for his dedication, perseverance, and unwillingness to admit that the manuscript could not be read, Newbold's “record of defeat was none the less a record of scholastic heroism.” From that day forward, however, no one thought William Romaine Newbold a hero. In fact, in his chapter in

The Codebreakers

entitled “The Pathology of Cryptology,” David Kahn's opening lines are about Newbold.

Although he had been reduced to poster boy for wishful cryptanalysis, Newbold was not its only victim. In 1926, Manly himself had produced a work entitled “Some New Light on Chaucer,” an attempt to link the pilgrims in the

Canterbury Tales

to real people. That work was greeted with the same enthusiasm as was Newbold's, and it turned out to be just as spurious.

It was in the same year as Manly's article that Albertus Magnus was made a saint, and everything that Newbold, those who had supported his version, and Voynich himself had said was now discarded. One could almost hear Lynn Thorndike sniffing, “I told you so.” The market for the manuscript dried up—a sale could probably not even have recouped the experts' fee—so Ethel Voynich ended up sticking it in a safe-deposit box, where it would remain for the next thirty years, until her death in 1960 at age ninety-six. (Further muddying an already unclear association, Ethel Voynich left her sixty percent ownership of the manuscript to Anne Nill, who had become her inseparable friend after Voynich's death.)

Through it all, however, there was no getting around that Marci had believed Bacon to be the author and so had Kircher and Rudolph. As to Dee, he had either believed the manuscript to be Bacon's work or known that it wasn't—perhaps he had never seen it at all. The possibility of forgery or hoax now became one of the more active hypotheses. People started looking at its provenance a little more carefully, and suddenly nothing about the manuscript was certain.

There were even some doubts that the manuscript was ever in Dee's possession. Dee liked to write his name in his books or jot down notes in the margins. None of these notations was present. Still, in the upper-left-hand corners of the pages were numbers written in a handwriting that has been confirmed by experts to be Dee's own. (There are dissenters even here, however.) This and his son's later, unrelated reminiscence that his father had been puzzling over a treatise written entirely in “Hieroglyphicks” while in Prague, and Dee's coincidentally obtaining six hundred ducats from Pucci, would all point in the direction that Dee had in fact sold the cipher manuscript to Rudolph.