The Furies

Authors: John Jakes

The Kent Family Chronicles (Book Four)

John Jakes

For my son John Michael

Book One: Turn Loose Your Wolf

Chapter V The Corn of San Jacinto

The Journal of Jephtha Kent, 1844:

Bishop Andrew’s Sin

Chapter I Cry in the Wilderness

Chapter III Christmas Among the Argonauts

Chapter IV To See the Elephant

Chapter V The Man Who Got in the Way

The Journal of Jephtha Kent, 1850:

A Higher Law

Book Three: Perish with the Sword

Chapter II Of Books and Bloomers

Chapter III The Man Who Thundered

Chapter V The Girl Who Refused

Our Heroine

S

O FAR AS READERS

are concerned, Amanda Kent, the leading character of this fourth novel in

The Kent Family Chronicles

, remains one of the two or three favorite members of my fictional family. Over the years I’ve heard from fans who have named daughters after her. And it still happens.

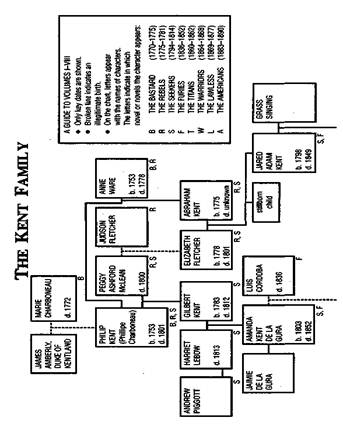

Amanda is one of my favorite heroines too—the second strong woman to appear in the series, the first being Philip Kent’s wife Anne Ware. Reviewers have observed that I have a penchant for creating strong female characters. Only belatedly, after several Kent novels were written and published, did I realize it was so. There are women as strong as Amanda still to come in the series, and in my other novels. Possibly this is because of my study of the nineteenth-century women’s movement, whose crusaders were often on the barricades for abolition as well as suffrage. I fell in love with the brave ladies who risked their reputations, their marriages, and sometimes their physical selves.

The Furies

covers a fairly lengthy span of time and geography: Texas, 1836, and the siege of the Alamo, the California gold rush in the late 1840s, then the turbulent national schism over slavery as played out in the east. As always, research inspired certain elements of the story. One of the most interesting was the Native American myth of the great vine to heaven. I was so intrigued by it I had to find a way to incorporate it into Amanda’s saga.

Another example: the novel’s opening sequence, which finds Amanda trapped behind the walls of the Alamo in San Antonio de Bexar. She witnesses the Alamo’s siege and fall and survives, as did Susannah Dickinson, wife of Almeron Dickinson of Tennessee, one of the many Americans killed during the fighting. Susannah and her little daughter, Angelina, whose charming girlishness took the fancy of General Santa Anna, later carried word of the Alamo atrocities to General Sam Houston, before the battle of San Jacinto, which won liberty for the Texas republic. Collaborating with the distinguished artist and book designer Paul Bacon, I did a book for young children about Susannah and Angelina.

I mention all this because Susannah is listed as the sole Anglo female to survive the massacre, but that is not to say other women weren’t present: some of the Mexican defenders of the Alamo had wives or sweethearts with them. These Latina women, alas, were never described, or even noted, among the survivors. It’s for this reason that Amanda’s past includes a husband named Jaimie de la Gura. With that last name, Amanda too would have been ignored on the casualty rolls. All during the writing of the Kent series, this is how research aided me in justifying the presence of certain fictional characters at great historic events, without falsifying the record as we have it.

I hope you enjoy Amanda’s adventures in a tumultuous time in American history, and I thank my friends at New American Library and Penguin Group (USA) for presenting them in this handsome new edition.

—John Jakes

Hilton Head Island,

South Carolina

“Mr. President, I wish to speak today, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American…

“It is not to be denied that we live in the midst of strong agitations, and are surrounded by very considerable dangers to our institutions and government. The imprisoned winds are let loose. The East, the North, and the stormy South combine to throw the whole sea into commotion, to toss its billows to the sky, and disclose its profoundest depths. I speak today for the preservation of the Union…

“I hear with distress and anguish the word ‘secession,’ especially when it falls from the lips of those who are patriotic, and known to the country, and known all over the world, for their political services. Secession! Peaceable secession! Sir, your eyes and mine are never destined to see that miracle…

“I will not state what might produce the disruption of the Union; but, Sir, I see as plainly as I see the sun in heaven what that disruption itself must produce; I see that it must produce war.”

March 7, 1850:

Daniel Webster,

to the United States Senate,

in support of Henry Clay’s

compromise bills

on slavery.

Book One

*

Turn Loose Your Wolf

Chapter I

The Chapel

i

S

HE AWOKE LATE IN

the night. At first she thought she was resting in her room, on the second floor of the adobe building local custom dignified with the name Gura’s Hotel. It was a hotel, of sorts. But the small, well-kept establishment on Soledad Street served customers other than those who wanted a meal, a glass of

aguardiente

or a bed to be used for sleeping—

For a few drowsy, delicious moments she believed she was back there. Safe. Secure—

Her mind cleared. Reality shattered the comforting illusion. Gura’s Hotel might only be a few hundred yards west of where she lay in the darkness, one torn blanket affording poor protection from the chill of the moonless night. But much more than distance cut her off from all that the hotel represented.

She was cut off by the four-foot-thick walls of the roofless chapel of the mission of San Antonio de Valero. She was cut off by the trenches among the cotton-woods—

los alamos

—that lined the water ditches outside. She was cut off by the heavily guarded plank bridges over the San Antonio River. She was cut off by an enemy force estimated to number between four and five thousand men.

Yet something other than the physical presence of an army was fundamentally responsible for her separation from the hotel. No one had forced her to come to the mission some said was nicknamed for the cottonwoods, and others for a garrison of soldiers from Coahuila that had been stationed here early in the century. Her own choice had isolated her.

In those lonely seconds just after full consciousness returned, the woman whose name was Amanda Kent de la Gura almost regretted her decision. She lay on the hard-packed ground, her head against a stone—the only kind of pillow available—and admitted to herself that she was afraid.

She had been in difficult, even dangerous circumstances before. She had been afraid before. But always, there had been at least a faint hope of survival. Only the most foolishly optimistic of the hundred and eighty-odd men walled up in the mission believed there was a chance of escape.

Turned on her side, her best dress of black silk tucked between her legs for warmth, Amanda stared into the darkness. In memory she saw the flag that had been raised from the tower of San Fernando Church on Bexar’s main plaza. The flag was red, with no decoration or device to signify its origin. To the men and the handful of women who took refuge in the mission when the enemy arrived, however, the meaning of the flag was clear. It meant the enemy general would give no quarter in battle.

Amanda’s mood of gloom persisted. Only with a deliberate effort of will did she turn her thoughts elsewhere. Pessimism accomplished nothing. Since she couldn’t sleep, she ought to get up and look in on her friend the colonel—

But she didn’t move immediately. She listened. She was disturbed by the silence. What had become of the night noises to which she and the others had grown accustomed during the past twelve—no, thirteen days?

She yawned. That was it, thirteen. It must be Sunday morning by now. Sunday, the sixth of March 1836. The first companies of enemy troops had clattered into San Antonio de Bexar on the twenty-third. Counting the extra day for a leap year, today would mark the thirteenth day of the siege—

She couldn’t remember when the night had been so still.

There was no

crump-crump

of Mexican artillery pieces hammering away at the walls. No wild, intimidating yells from the troops slowly closing an armed ring around the mission. No sudden, terrifying eruptions of music as the enemy general’s massed regimental bands struck up a brassy serenade in the middle of the night, to keep the defenders awake, strain their nerves. The general knew that tired men were more susceptible to fear—and less accurate with their firearms—than rested ones—

None of those tactics had worked, though. If anything, the resolve of the garrison had stiffened as the days passed; stiffened even when it became apparent that Buck Travis’ appeals for help, sent by mounted messengers who dashed out through the enemy lines after dark, would not be answered.

Colonel Fannin supposedly had three hundred men at Goliad, a little over ninety miles away. Three hundred men might make the difference. But now everyone understood that Fannin wasn’t coming. He hesitated to risk his troops against such a huge Mexican force. That message had been brought back by one of Travis’ couriers, the courtly southerner Jim Bonham. He had risked his life to return alone when he could have stayed safely at Goliad after delivering Travis’ plea to Fannin.