The General and the Jaguar (38 page)

Read The General and the Jaguar Online

Authors: Eileen Welsome

The bodies were eventually returned to their families. To their sorrow, the local priest would not allow the funerals to be

conducted in church and only “meager” ceremonies were held. The corpses were dressed in cheap clothing and placed in pine

coffins built by local carpenters and stained black by a local painter who did not have enough pigment to give both boxes

a full coat. Then the coffins were loaded onto two-wheel carts and hauled by burros to a weed-choked

campo santo.

Twelve mourners, wearing black shawls and threadbare clothing, struggled along behind the carts, the only dark spots on that

jewel-bright May morning.

A few days later, members of the Mexican civil-defense group led Pershing’s cavalry to a weapons cache, where Villa had hidden

four hundred rifles and eleven machine guns. The cavalrymen were jubilant over the discovery, but it would have dreadful ramifications

for the people of Namiquipa.

Pershing would receive more good news a few days later from Chihuahua City, when the Carrancistas sent him a telegram stating

that Pablo López, the architect of the Santa Isabel train massacre, had been executed.

P

ERSHING AND HIS HEADQUARTERS

staff knew from their informants and prisoner interrogations that Pablo López had been wounded and was exceedingly vulnerable

to capture. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Allen, with a provisional squadron of eighty-four men from the Eleventh Regiment, had

come across his tracks on April 9. Allen suspected the tracks belonged to López because the Mexican was supposed to be riding

a cavalry horse that was missing its right front shoe. The U.S. troopers searched the hacienda where López’s parents worked

and then picked up his trail again on a faint path leading to some caves. Allen had been on the verge of searching the caves

when he learned of Frank Tompkins’s skirmish with the Carrancistas. Fearing for the safety of the major and his men, Allen

had reversed course and raced to Parral to back him up.

López had indeed been living in a cave, though it’s not clear whether it was one of the locations that Colonel Allen was about

to search. When López’s supplies ran out, old friends in the hills brought him what food they could spare. In late April,

feverish and malnourished, he could stand the isolation no longer and gave himself up to Carrancista troops. He was taken

to the penitentiary in Chihuahua City and informed that he would be executed as soon as he could walk to the firing squad.

While he was waiting, an Associated Press reporter went to his jail cell to interview him. López was dozing on a cot, clad

only in an undershirt, cotton trousers, and black socks. His left leg was wrapped in bandages. “Well, señor, what do you wish?

Have you also come to gloat over the poor captive for whose blood your soldiers are so eagerly thirsting? A number of other

curious gringos came to see me recently, but I refused either to see them or talk to them.”

When the reporter mentioned that he was of Irish descent, López consented to an interview. “Ah,” he said. “You are not then

a gringo. Well that makes a little difference; you have revolutions in your own land, is it not so? Yes, my friends keep me

posted on outside news. If it were not for them I would starve.”

The reporter offered López a cigarette and he took it, remarking how expensive tobacco had become in Mexico. Then he settled

back and began to talk. His voice was low, his words deliberate, his sentences forming like drops of water in the pooled darkness.

He seemed like an intellectual, not the unlettered peon that he professed to be, and in no way did he resemble the frightened,

craven bandit he had been portrayed as in some newspaper accounts. Mesmerized, the reporter would later write that it was

as if Villa himself were speaking.

López inhaled the smoke deep into his lungs and blew it out. He had been extremely handsome once but malnutrition and suffering

and war had aged him. He was a scarecrow, arms and legs emaciated, his hair like thatch, his skin soft as a curing tobacco

leaf thanks to so many long, sunless days. He said he entered life as a poor, ignorant peon. “My only education was gained

in leading the oxen and following the plow. However when the good Francisco Madero rose in arms against our despotic masters,

I gladly answered his call.” Villa, he said, “was the object of worship of all who were ground under the heel of the oppressor.

When the call came I was one of the first to join him and I have been his faithful follower and adoring slave ever since.”

“Don Pancho,” López continued, was convinced the United States was too cowardly to try to win Mexico by arms and believed

that it intended to “keep pitting one faction against another until we were all killed off, when our exhausted country would

fall like a ripe pear—

como una pera madura

—into their eager hands.” Villa, he added, was convinced that Carranza had sold out to the Americans and wanted to trigger

an intervention before the “Americans were ready” and while “we still had time to become a united nation.”

López said he was forced to surrender because he was literally starving to death. “Would I have surrendered to the gringos?

No, señor, many times no. I have been often in tight places when wounded, but have never thought of surrendering. If the gringos

had found me I would have fought to the last and kept one cartridge for myself.”

When asked about the train massacre, Lopéz sighed. “Things might not have gone as they did if it had not been that there were

other jefes there among whom there was a spirit of deviltry. Perhaps we would have been content with only the Americans’ clothes

and money. But, señor, they started to run, and then our soldiers began to shoot.

El olor de la polvora nos enciende la sangre

—The smell of powder makes our blood hotter. The excitement grew and—ah, well señor, it was all over before I realized. Yes,

I was sorry when I had time to cool down and reflect.”

Speaking in the same candid tone, he also admitted that the Columbus raid had netted them little. “Were we disappointed over

the Columbus raid? Well, all we got there were some horses, many bullets and a lot of hell.” But none of that mattered now,

he said, shrugging his shoulders. “I am bound for Santa Rosa [Chihuahua’s execution place] when I am able to walk there. I

would much prefer to die for my country in battle, but if it is decided to kill me, I will die as Pancho Villa would wish

me to—with my head erect and my eyes unbandaged—and history will not be able to record that Pablo López flinched on the brink

of eternity.”

On June 5, when the clock in the cuartel struck eleven, López was marched from his prison cell to the place of execution.

He smoked a cigar with his guards and then walked up to the bloodstained, pitted wall. A friend supported his right side and

he used a homemade crutch on his left. López was carefully dressed, wearing a brilliant white shirt that would help his executioners

find their target and dark, pin-striped pants that would hide the unmanly stains that would come afterward. He removed his

plain straw sombrero, threw away the crutch, and smiled until all his white teeth showed. His unbandaged eyes looked at the

firing squad.

En el pecho, hermanos, en el pecho

—In the breast, brothers, in the breast.

The commander barked an order and the soldiers lifted their rifles to their shoulders and fired. Five points of red appeared

on his white shirt and López toppled over dead. The firing squad had done its job well and there was no sign of the writhing

that sometimes followed the executions. But the commander walked over to the upturned face anyway, pulled out his pistol,

and gave the dead man the

tira de gracia

—the coup de grâce—the same mercy shot that López had once ordered at Santa Isabel for the naked, squirming miners.

A Terrible Blunder

P

ERSHING’S ELATION

over the deaths of the high-ranking Villistas was short-lived as the tension between the Carrancistas

and the expeditionary forces continued to grow. Large numbers of Mexican troops were massing to the east and west of Pershing’s

line and Venustiano Carranza continued to press for the immediate withdrawal of the U.S. troops. On June 16, General Jacinto

Treviño, commander of the Carrancista forces at Chihuahua City, sent Pershing the following telegram: “I have orders from

my government to prevent, by the use of arms, new invasions of my country by American troops and also to prevent the American

forces that are now in this state from moving to the south, east, or west of places they now occupy. I communicate this to

you for your knowledge for the reason that your forces will be attacked by the Mexican forces if these indications are not

heeded.” In order to make sure that Pershing understood the gravity of the situation, three Carranza officers then visited

his camp and went over their orders by lantern light. The threat was like waving a red flag in front of Pershing. He bade

the Mexican officers a curt good night and fired off a terse telegram to Treviño. The U.S. government had placed no such restrictions

on his movements, he wrote. “I shall therefore use my own judgment as to when and in what direction I shall move my forces

in pursuit of bandits or in seeking information regarding bandits. If, under these circumstances, the Mexican forces attack

any of my columns, the responsibility for the consequences will lie with the Mexican government.”

Two days later, on June 18, President Wilson called up the militia from forty-four additional states. Secretary of the Navy

Josephus Daniels ordered sixteen warships to both coasts of Mexico as a “precautionary” measure. And Secretary of State Robert

Lansing put the finishing touches on a scalding, six-thousand-word message in which he flatly refused Carranza’s demands for

withdrawal and rebuked him for his insulting and bellicose language. U.S. citizens began fleeing Mexico and General Obregón

sent out a message, calling upon all Mexicans to enlist in the armed forces in order to repel the “foreign invaders.”

In a highly provocative move, General Pershing on this same day decided to dispatch two cavalry patrols to reconnoiter the

land around Villa Ahumada, eighty miles east of his base camp. His spies had told him that eight to ten thousand Carrancista

soldiers were massing there and he wanted to check out the rumors, even though he knew such patrols could ignite a war. “Cavalry

patrols for the safety of our forces must be sent out day and nightly, and if there is a fight it will likely start over these

patrols,” he told reporters.

Captain Charles Boyd, a white officer in the African-American Tenth Cavalry Regiment, was selected to lead one patrol. Pershing

had known Boyd for many years and considered him a competent and industrious officer. Boyd seemed almost a carbon copy of

Frank Tompkins, proud, ambitious, and spoiling for a fight. He was a graduate of West Point, but noticeably fat now, with

a mouth filled with gold crowns and a long, aquiline nose that cleaved down through two slackening cheeks. No written copy

of Pershing’s instructions has been found, but Boyd was jubilant when he returned from a meeting with the general. He waved

a piece of paper in front of his fellow troopers and said teasingly, “I’ve got peace or war” right here.

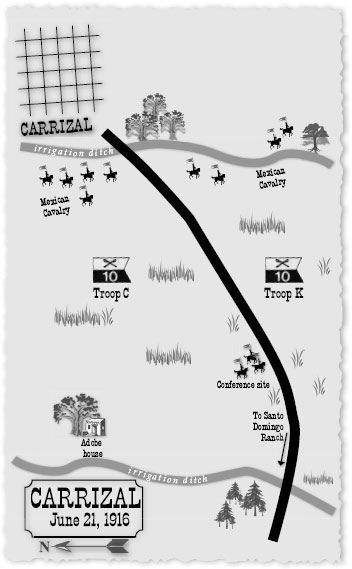

For reasons that are not clear, Pershing ordered Troop K, also from the Tenth Cavalry, which was stationed at Ojo Federico,

about two days’ march from headquarters, on the same mission. A slender and cautious-looking officer named Captain Lewis Morey,

also a West Point graduate, led this contingent. The two troops started east from their separate locations, moving across

the arid and sparsely inhabited scrubland.

Boyd’s second in command was Lieutenant Henry Adair, aristocratic, confident, nearly bald except for a few strands of dull

red hair hanging from the back of his head. Also accompanying him was Mormon scout Lem Spilsbury, who still bore a childhood

scar on his cheek from where he had been gored by a bull. His mother had stitched up the wound, dousing it first in turpentine

and then sewing it with stiff thread, but the hole never closed completely and became a great source of amusement to Lem,

who often forced water through the opening to entertain his friends and family.

As they jogged along, Boyd confided to Spilsbury that U.S. troops were poised to counterattack if Pershing was molested. “If

the Mexican troops fire on us without provocation,” he said, “just as soon as that word gets back to the line, General Pershing

will attack on the south all along the line and General Funston will immediately attack along the border.” In fact, the War

Department had drawn up much more detailed plans than that. In the event of outright war, the United States planned to immediately

occupy the international bridges and the Mexican border towns, seize Mexico’s railroads, and dispatch another ten thousand

troops to Pershing’s camp. Then, three columns of soldiers composed of regular troops and militia would be assembled in El

Paso, Brownsville, and Nogales. The El Paso column, working in tandem with Pershing’s beefed-up troops, would push south,

driving the Carrancistas south of Chihuahua City; the Brownsville column, together with five thousand soldiers who would come

ashore at Tampico, would force the Mexican troops from the states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas; and the Nogales

column would sweep the Carrancistas from the state of Sonora.