The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (11 page)

Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

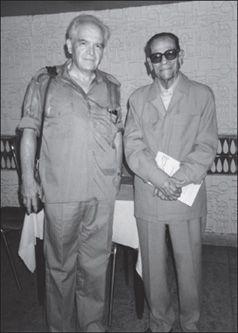

They toured Egypt and met the famed Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, who later received the Nobel Prize for literature, at his home in Cairo. My father had written his dissertation about Mahfouz, but being an Israeli and a retired general, he had not been able to meet him until then. Over the years, my father returned to visit Mahfouz several times. He loved the normalcy of taking a bus from Tel Aviv to Cairo, going to the café that Mahfouz was known to frequent, and sitting there with the great writer for hours. He loved the Arab world—the neighborhood in which Israel was founded, not just the piece of land on which it had set up its state.

Riding the success of the 1979 peace pact with Egypt, in the 1982 national elections Menachem Begin won a second term in office as prime minister. However, this term was marked by the invasion of Lebanon, a devastating war that would later be known as Israel’s Vietnam. Testing the limits as he always did, in early

1983, shortly after Arafat was driven out of Lebanon by the Israeli invasion, my father embarked on a secret mission to Tunisia to meet with the PLO chairman himself. He was joined by Uri Avnery and Dr. Yaakov Arnon, an economist, former general director of the Israeli department of treasury and a close friend of my father. And on the Palestinian side, along with Chairman Arafat, were Mahmoud Abbas and Dr. Issam Sartawi. The meeting was later publicized, and the photo of them together made the press worldwide.

My father in Cairo with Egyptian author and Nobel Laureate for Literature, Naguib Mahfouz.

It wasn’t long after this historic meeting that Dr. Sartawi was murdered. It happened April 10, 1983, during a meeting of the Socialist International Conference in Portugal. The presumed culprit was the Abu Nidal terrorist gang operating out of Iraq, whose loyalties are shrouded in mystery to this day.

Sartawi’s death was a dark day for my family. I happened to be watching TV when it took place. Dr. Issam lay on the ground in a pool of his own blood in broad daylight in a hotel lobby. It took me a few seconds before I could utter the words: “Dad come quick, Issam Sartawi was shot!” Surrounded by parliamentarians and heads of state, including Shimon Peres, who was there as the Labor Party leader, Issam Sartawi was gunned down.

Israeli Council for Israel-Palestine Peace meeting with Yasser Arafat in Tunis.

My father was in his study when I called him. When he realized what had happened, he was stricken and motionless. Though he did not say a word, I could see that after the death of his beloved brother Dubik, this was the saddest day of his life. Later on, he gave a statement in which he said, “Sartawi was killed because he was reaching out to Zionists. He had literally given his life for peace.” My father reminded people of this each time doubt was cast upon the sincerity of the Palestinians’ desire for peace.

The next year, my father was among the founding members of a joint Jewish-Arab political party, the Progressive List for Peace (PLP). Their Palestinian-Israeli

9

partners were headed by Mohammed Mi’yari, a veteran activist and human rights lawyer, and Bishop Riah Abu-el-Assal, vicar of the Anglican Church in Nazareth, who was later the Anglican bishop of Jerusalem. My father had lent his name and reputation to several political parties over the years, but he had no real interest in becoming a politician. For the PLP however, he agreed to be the number two on the list in the 1984 national elections.

Right-wing nationalist parties made several attempts to outlaw the PLP and prevent it from running in elections. They compared it to the racist Kach Party, led by US-born Rabbi Meir Kahane, and said that the elimination of both would be a fair trade. Kach was an overtly racist Jewish party that ran on a platform calling for forcibly transferring all Palestinians out of the country. One party called for peace and reconciliation and one for ethnic cleansing, yet the claim was that they were equally extreme. The Israeli Supreme Court, which

considered it utterly ridiculous that a party cofounded by Matti Peled should be considered “a danger to state security,” ruled that both parties should be allowed to run. The Progressive List for Peace won two seats in the Knesset in the next elections, and my father served one four-year term.

He enjoyed his years as a parliamentarian, and as with everything he did, he poured all of his heart, soul, and intellect into it. His term coincided with the tense atmosphere of the outbreak of the first Palestinian Uprising, or

Intifada

, but he did not confine himself to speaking about the conflict. He took great interest in an array of subjects, in some cases finding common ground with staunch right-wingers.

He quickly gained a reputation as one of the most diligent and industrious members in the history of the Knesset. He would read for up to a week to prepare a ten-minute speech, and his speeches were said to resemble academic lectures. It was not uncommon for radical right-wing adversaries, many of whom had never served in the armed forces, to try to shout him down as a traitor. He felt disgusted by the chase for media attention that was common among Knesset members and refused to insert provocative lines into his speeches that would be sure to grab headlines. He didn’t miss a single meeting in four years, which was highly unusual in a Knesset whose chamber is usually mostly empty.

He still preferred Arab literature to politics, and when his four-year term in parliament was over in 1988, he was pleased to return to academic life. Immediately he and my mother left for another year-long academic sabbatical to Harvard, where they had a terrific time together.

Gila and I were already married at this point. At the end of 1987, before my father’s term was up, we left Japan—where we had been living for close to two years—and spent a few weeks in Israel. We actually got to see my father at the Knesset. He took us on a tour, and we met his colleagues, and we sat in on a session in the chamber. Then, in the fall of that year Gila and I moved to the U.S., intending to spend no more than two years before returning to Jerusalem. When my parents arrived at Harvard, my mother came to visit us in California, after which Gila and I went to Massachusetts and spent a very pleasant week with them at their apartment in Cambridge.

By then, the Palestinian uprising had begun. Images were beamed around the world of Israeli soldiers beating and shooting Palestinian children wielding nothing but stones in their hands. This was a bona fide grassroots revolution, and it caught everyone by surprise. As Israel was looking for ways to crush this popular revolt, the widely circulated, unofficial order from the defense minister was to “break the Palestinians’ bones and deliver casualties” and indeed, many civilians were shot. Israel’s defenders claimed that Israel was using rubber bullets, in order not to kill or harm but merely scare them away.

My father kept a rubber bullet in his coat pocket, and he would take it out when he gave talks about the conflict back home. He’d scratch the rubber off the bullet to demonstrate that the bullets were made of steel and only thinly covered with rubber.

Speaking in America was nothing new for my father. He had first visited as an Israeli VIP, a general who spoke for the government. Gradually, as his opinions began to shift, his speeches did, too. He was invited by various peace groups and would sometimes spend weeks traveling and speaking. Having been a member of the Knesset and a military expert in the area of logistics and armaments, he was ready to argue from both a political and a military standpoint that Israel was much better off making peace than arming itself and maintaining the occupation of the land it had conquered in 1967.

One point he came back to often was that the best thing America could do for Israel was to stop selling it weapons and giving it free money. “Until 1974,” he told the audience of Temple Emanuel in San Francisco on one occasion, “Israel had not received foreign aid money and we did fine.” He then looked at the people seated in the audience and continued: “Receiving free money, money you have not earned and for which you do not have to work, is plain and simply corrupting.” He argued that the weapons the U.S. sold to Israel were corrupting the country and were being used to maintain the occupation and oppression of the Palestinians.

“It is bad for Israel, it is morally wrong, and it is illegal,” he always said.

At the end of 1992, Yitzhak Rabin was elected as prime minister once again, vowing to make peace. By the end of 1993, he seemed to come to the same conclusion as my father, and he signed the Oslo peace agreement known as the Oslo Accords and shook hands with Yasser Arafat. This was done on the White House lawn as the entire world looked on, and I believed at that time this was the beginning of the end of the conflict, built upon the hard work of my father, Dr. Sartawi, and others like them. The two-state solution, which before had been unthinkably radical, had gone mainstream. I felt certain that peace was now inevitable.

The process was a long one, but the pace of reconciliation seemed very fast. The Israeli army was pulling out of major Palestinian cities, and Palestinian expatriates began returning to build what they thought was their soon-to-be independent state. Israelis were visiting Palestinian cities as tourists and guests rather than as soldiers. Things were moving rapidly, and euphoria was in the air.

My father strongly supported the Oslo Accords at first, and he wrote that Rabin had “crossed the Rubicon.” (He was referring to Julius Caesar and his army crossing the Rubicon River upon Caesar’s return to Italy. In other words, it was an irreversible act of great significance.) They were signed the same year my father, Uri Avnery, and others formed Gush Shalom, the grassroots Israeli peace bloc.

But as time wore on, my father lost patience. “Settlement expansion in the West Bank continued, and good faith deadlines passed due to Israeli inaction,” he claimed. He knew that a slow pace of peace coupled with ongoing settlement expansion would give ample opportunity to extremists on both sides to renew the violence. He criticized and described what he saw: “Rabin is stalling and disregarding aspects of the agreement that would solidify Palestinian statehood, like ending the total Palestinian economic dependency on Israel.” Also that “Arafat, who had

put everything on the line for peace, was being treated with contempt.” In contrast with Sadat, who visited Jerusalem with great fanfare and was allowed to pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque, Arafat was never permitted to enter the city.

My father, true to his nature, read the fine print and found that the Oslo Accords were seriously flawed. On the occasion of his 70

th

birthday, he gave an interview with

Ma’ariv

that became the weekend cover story. The headline read, “Rabin Does Not Want Peace.”

10

This statement permanently severed the relationship between Rabin and my father, two introverted men of steel who for thirty years had fought side by side and worked together to build the Israeli army, and in 1967 led it to the final conquest of the “Promised Land.”

In another interview he gave to the daily

Yedioth Ahronoth

in late 1994, my father said, “The Palestinians believed the Oslo Accords would lead to a Palestinian state, but Rabin had no intention of letting that happen.” Again in his dry, analytical style, he claimed “the Palestinians might be allowed to collect their own garbage and print their own passports, but this mini-state would ultimately be controlled by Israel.” Meanwhile, the rest of us chose to follow our hearts and believe that the leadership would produce the peace we all hoped for. Ultimately, my father was right about the Oslo Accords.