The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (23 page)

Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

The army is answerable to no one and the residents of Bil’in have no recourse, no law that protects them or their property. Still, non-violence was like a religion for these men.

I knew that violent resistance, or terrorism—for which the Palestinians had become known around the world—represented only of a fraction of Palestinians. But until then, I was not aware of the prevalence of more peaceful responses. Khaled and Ali from the Bereaved Families forum had spoken of non-violence and now I was hearing about it again. In fact, the bulk of Palestinian resistance has always been non-violent, but the violent armed struggle is what receives media attention. The vast majority of Palestinians in Israeli prisons were convicted of non-violent political resistance. What makes the Bil’in non-violent movement unique is their persistence even in the face of violent Israeli measures.

We were all getting hungry and Iyad and Eymad asked to use my car to go buy groceries for dinner. Everything I’d been taught as an Israeli told me that lending a rented car with Israeli plates to a couple of young Palestinians in the West Bank was a breach of security of the highest order. These guys might seem nice now, but did I know who they really were? Wasn’t it the perfect opportunity to take advantage of a naive Israeli like myself? What if they disappeared, leaving me stranded here, where I might be killed? What if they use the car to plant a bomb? It was not an easy decision.

Letting go of my fear and placing my trust in these committed young activists was not a choice, it was a mission. I had driven all the way to Bil’in to meet them, and I had spent the entire day with them. They were the type of men who would make any nation proud. They were husbands and fathers of young children, and they deliberately and consistently refused to engage in violence, just as they refused to accept the injustice imposed on them by the Israeli occupation.

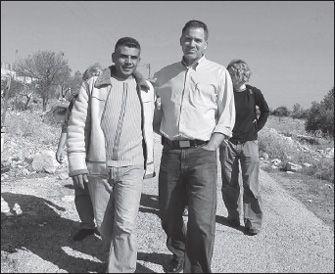

Another companion in Bil’in, Iyad Burnat and I walking to the weekly protest

.

I gave them the keys to the car. Half an hour later they returned with meat, vegetables, and yogurt, and soon we were feasting on kebabs, roasted veggies, bread, olive oil, and salad.

By the time we finished dinner it was getting dark, and I still had to drive back to Jerusalem. They pointed me in the right direction, and off I went, frightened once again, still involuntarily recalling stories of Palestinian mobs killing innocent Israelis. I told myself that these guys would not put me at risk. They knew I’d be safe, or they would not have let me drive alone.

Along the way, I picked up a couple young schoolboys who asked for a ride. I wanted to fight the urge to run away and to embrace the fact that I was there. If these Palestinian boys were not afraid to get a ride from an Israeli, why should I fear giving them one? They rode with me for a couple miles and thanked me as they got out of the car at their destination. And as I continued to drive through the dark streets of Bil’in, mostly empty by now because of the late hour, I was comforted by their thanks, and by the trust I had in my new friends from Bil’in.

1

On July 9, 2004, the International Court of Justice declared the route of the barrier to be in violation of international law because it was built within occupied Palestinian land rather than along the Green Line border. The vast majority of the wall is built inside the West Bank, not along the border.

The Commanding General’s Order

In April 2007, Nader and I went to visit the institutions in Israel and the West Bank that had received our donated wheelchairs. Nader flew to Amman, Jordan, where he has a home, and I flew to Tel Aviv. We planned to meet in Jerusalem.

It was going to be our victory lap. “Wheelchairs to the Holy Land” had succeeded: We had served children on both sides of the conflict, and we had overcome a lot to get the project done. But there was a tremendous gap between my perceptions and reality. Instead of a victory lap, the trip evolved into a long journey that led to a sobering discovery. I arrived in Jerusalem right after the Passover Seder, and I spent a few days with my family before going to meet Nader. It was Easter, and my sister Ossi suggested that we go see one of the most terrific and rare sights taking place in Jerusalem that year.

Ossi, the younger of my two sisters, has always been quiet, smart, and very funny. She and I became friends relatively late in life, probably because I was six years younger than her. She studied and became quite an expert on Eastern Christianity. In particular, she knows a lot about Christian iconography and visiting the various churches in the Holy Land with her is an enlightening experience.

Every four years Easter is celebrated by all the Christian denominations on the same day, and 2007 was one such year. Ossi, her husband Haim, and I ventured into the Old City at 10 p.m. to see what is called

Sabt al Nur

, or “Saturday of Light.”

The Old City is contained within ancient walls, and within its narrow streets and alleyways are kept the ancient traditions of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim faiths. It is both a spiritual place, with its churches and mosques and synagogues, and also very earthly, with stores that offer freshly butchered meat, freshly picked fruit and vegetables, sweets, herbs, clothes, fabrics, and knick-knacks of every kind. I have a favorite route that I take every time I visit the Old City, and every time I discover something knew.

On that particular night, when Ossi and I went, young and old, men and women, pilgrims from around the world converged on this small city and marched holding torches, singing and celebrating the resurrection. I had never seen so many people in the Old City, and it amazed me that in all the years I had lived in Jerusalem I had no idea that this took place. We went from one church to another

to see how each denomination celebrated the occasion that defined their faith, the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

We began with the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where old women climbed steep staircases to be close enough to kiss an image of Christ, and priests performed ceremonies in all languages. On the small roof, hundreds of Ethiopian pilgrims huddled together as their priests prayed and performed their indigenous Christian ceremonies. It was moving to see such devotion, and also quite frightening to see how crowded the spaces were and how little was set up in the way of public safety.

By 2 a.m. we came to the glorious Russian Orthodox Church, whose golden onion domes set it apart on the hill across from the Temple Mount. After the service, the congregation exited the church, and the priest made the famous announcement: “

Cristos Anesti”

(Christ has risen), and the crowd replied: “

Alithos Anesti

” (He has risen indeed). Here the priest announced it in every conceivable language, and the crowd responded in their respective native tongue.

I have spent a great deal of time in Jerusalem, and she never ceases to amaze me.

When it was time for Nader and me to meet, I felt worried. I have heard from many Palestinian-American friends how the Israeli authorities harass them when they enter Israel, often holding them for hours before letting them through. I also knew that Nader made a trip from Jordan to Israel with his family six months earlier, 18 people in all including sons and daughters-in-law and grandchildren, some of them babies. As they traversed the bridge into Israel at the northern crossing, the Israeli security officials took their passports and detained them for the entire day.

The Israeli authorities provided them with no explanation, no food or water, and no courtesy. Their passports were returned to them at the end of the day when the crossing was closing. They were all exhausted, and by this point no public transportation was available, which meant they were stranded. Eventually they were able to call a minivan driver who transported workers at the crossing. They paid him several hundred dollars to come back and take them to Nazareth. In the past, when Nader and I crossed together, he was allowed to go through with no delays, and I had good reason to believe that with an Israeli citizen beside him again he would not be harassed.

Nader is a strong and resilient man, but this was more harassment than anyone should have to endure. So I suggested to Rami that he and I take a short trip to Jordan, spend a few days with Nader in Amman, and then all three of us could travel to Israel together. With Rami and I present, I was certain that things would go more smoothly.

Crossing from Israel eastward into Jordan is more than just crossing a river. The Jordan River is the gateway to the East and to the Arab world. My mother had served in the British army and was able to travel all over the Arab world. Stationed in Cairo, she had traveled as far as Beirut and Damascus. My father had visited

Naguib Mahfouz in Cairo several times, and now it was my turn to get to know the larger neighborhood.

With Nader at Fatah Headquarters in Ramallah. Fatah was considered a dangerous enemy for as long as I could remember, but now I was there with friends

.

Israel and Jordan have had peaceful relations since 1995, but you can tell that the relationship between the two countries is still strained. In the huge immigration terminal on the Israeli side of the border hangs a larger-than-life photo of the late Jordanian King Hussein bin Talal lighting a cigarette for the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. This casual, friendly gesture demonstrates the close relations that existed between the two men. The emptiness of the terminal bore witness to great expectations that had not materialized.

This would be my second trip to visit Nader in Jordan. The first time, he met me at the northern crossing of the Jordan River and took me to see the ancient Roman city of Jerash before heading south to Amman, where we spent most of the time meeting his friends.

Rami, too, was excited about the idea, and we left with a sense of adventure. As soon as we arrived in Amman, Nader met us and took us to have lunch at Jabri’s, a popular local chain restaurant that serves great food and sweets. Then we spent some time at Nader’s house to rest and talk for a bit. In the evening, we walked around Amman as much as we could and ended up at the Del Mondo Café. We drank coffee, Nader and Rami ordered hookahs, and we sat and talked for hours.

Nader pointed to the people in the café. “Look around you,” he said. “When I lived here 20 years ago you would never see women in a café like you do today.”

I reflected on what he said and added, “And look at the three of us, two Israelis and a Palestinian sitting together in an Arab capital, drinking coffee, without a worry in the world. That too was not possible 20 years ago.”

I really wanted to see Saladin’s famous castle at Ajloun in Northern Jordan. So on Friday morning, the day we returned to Israel, Nader went to the mosque to pray and then we took a cab to Ajloun. It was a cold and cloudy day with a light rain, which made the scenery on the way to Ajloun hauntingly beautiful and the scene at the castle itself even more dramatic. The village of Tishbi, where the prophet Elijah was born, is just behind the castle to the east. Mount Tabor rises to the west, and on a clear day one can see the Sea of Galilee. The castle itself is magnificent, typical of castles built all over ancient Israel/Palestine

1

during the Crusader period. It overlooks the hills and valleys extending for miles around.

From Ajloun, we proceeded to the border to enter Israel. The closer we got, the more tense we all felt. As we entered the terminal, I glanced at Nader. He appeared nervous, his face pale, his lips dry. I could tell that visions from his previous experience were still fresh in his mind.

At passport control, I handed the girl behind the counter all three passports together, Nader’s U.S. passport sandwiched in between our two Israeli ones. “Are you together?” she asked.

“We are,” I said.

“There is a problem with his passport, he should sit down and wait. Does he speak Hebrew?”

“No he does not, what is the problem?”

“His name raises a red flag,” she said, “and it may take a very long time. We have to wait for an OK from headquarters, and it is late.”

Rami demanded to know the nature of the problem. “We are not leaving without him,” my brother-in-law said. No sooner did he finish his sentence than a young man with an unshaven face, dressed in jeans and t-shirt, came out to see us.

“His name raised a red flag, we can do nothing until we hear from headquarters.” His Russian accent was heavy. It takes a special kind of arrogance, or ignorance, for someone who is new to a country to keep an older person (who was born in that country and whose ancestors were born in that country), out. I said nothing.

We told him who we were, we told him who Nader was, and we told him we were not leaving without him. “He deserves a red carpet VIP treatment for his work with Rotary and the wheelchair project, not to mention the unnecessary

hassles you guys had put him through six months ago. You would do well to take that into consideration.”

Rami could tell that I was beginning to lose my patience. “Miko calm down,” he whispered. Then he turned to the young man, who had not yet identified himself. “You have no right to treat people like this without an explanation. You owe him an explanation and an apology.” Now he was losing his cool.

“My hands are tied. We have to wait for word from headquarters. It may take a long time.”

“We will wait right here until you clear it up,” I said.

He disappeared into his office. The girl behind the counter came out with her backpack slung over her shoulder, her work-day concluded. It was getting close to 8 p.m., when the crossing closed. Ten minutes later the young man returned with Nader’s passport.

“The red flag had been removed from Nader’s name. This will not happen again,” he promised.

The entire time Nader sat there quietly. He was unable to communicate with the authorities, and Rami and I had no intention of letting them get away with harassing him. As it turned out we were delayed only 30 minutes.

We took a cab to Nazareth, where we spent the night. In the morning, we met with members of the Rotary Club of Nazareth, who showed us the facilities where the wheelchairs had been distributed, and that night we headed off to Jerusalem. The next morning, Nader and I drove to Yad Sarah, or Sarah’s Hand, an important charity in Israel that lends medical equipment to people in need for free. When my father was dying, we decided to care for him at home, and Yad Sarah provided the wheelchairs and other necessities free of charge and for as long as they were needed. It felt good to be giving back by providing them with new wheelchairs.

At Yad Sarah volunteers do most of the work, and most of them are deeply religious Orthodox Jews. As we toured their building, I saw Nader looking around at the people. “There are many orthodox Jewish people here,” he observed. I realized this was the first time Nader had ever been around Orthodox Jews.

“Yes, religious people are known to volunteer to do charity everywhere in the world,” I told him. We spent an hour touring the facility before heading to Beit Jala to see the wheelchairs at the Arab Rehabilitation Hospital.

Beit Jala is adjacent to Bethlehem, and I had not been to Bethlehem in at least 20 years. A friend took us there, driving down a road that did not require passing through a major checkpoint—instead there was a small roadblock with soldiers waving cars through. My friend dropped us off at Muna Katan’s office, and she and her father took us to Bethlehem for lunch. After lunch, Muna’s father drove us around for a while, and he showed us the wall that surrounds this ancient city. The

ugly concrete structure was built around the city by Israel to separate Palestinians from lands that Israel wants to settle. There is graffiti all over the wall, a combination of art, poetry, and statements of resistance. Nader and I asked to step out of the car to get a closer look.