The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (32 page)

Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

None of this has provided Khaled and his family immunity. In January of 2010, Israeli soldiers came to Khaled’s house in Beit Ummar at two in the morning, banged on the door, and threatened to blow up the house if the family didn’t open up immediately. They then threw everyone out of the house, including young and terrified children. They ransacked the house leaving a trail of destruction, and when they emerged the soldiers singled out Muhaned, Mu’ayed’s twin brother, and took him away. After spending 12 months in prison without being charged, Muhaned was finally tried and sentenced to a total of two years in an Israeli prison. Meanwhile, Khaled’s entire family was denied entry into Israel and thus prevented from visiting Muhaned.

Over the years, Bassam Aramin, father of ten-year-old Abir, who was shot by an Israeli soldier, became known for his dedication to reconciliation and his relentless activism for Palestinian freedom. He coined the term “Palestinian Bar Mitzvah”

1

to describe the horror most young Palestinians have to endure at the hands of the Israeli soldiers. He wrote an article with the same title after the Israeli army put his son Arab through a real-life nightmare. This nightmare, Bassam later wrote, which took place less than two years after his daughter Abir was killed, is the daily bread, the rite of passage of every Palestinian boy.

It happened on a Friday in July 2008, when Bassam’s older son Arab, 14 at the time, asked to go on a rare excursion with friends to the Sea of Galilee in the north. For days he had begged Bassam to let him go. At first Bassam refused, insisting that

he was too young to be traveling so far from home without his parents. But, finally he gave his permission, on the condition that Arab would remain in constant phone contact with him throughout the day.

Arab traveled by bus with about 45 people, mostly teenagers and families with children, all of them legal residents of Israel. Arab called to check in after the bus was underway, and everything was going fine.

The day was a huge success, and around 11:00 that night Arab called to say that they would be home in half an hour. When an hour later they had not returned, Bassam became worried and he called, wondering why they were late.

“There are a lot of soldiers here,” Arab whispered into the phone. “The police stopped the bus, we don’t know why, and we’re in Jerusalem—the soldiers are telling us not to talk on the phone, I’ll call back later.”

Bassam later described the situation in his article: “In the industrial neighborhood of Wadi al-Joz in Jerusalem, Israeli troops on motorcycles, along with police and army units, were stationed on the path the bus was taking from Tiberias back home to Anata. When the bus drove by, the soldiers demanded that the driver stop.”

Arab later said to his father, “At that moment all I could think of was Abir.”

“We are from national security,” the soldiers told the passengers, and they ordered the young men, about 10 of them, to begin taking off their clothes in the bus, in front of the women and girls. Then they took these young men off the bus one by one and had them lie down on the ground, which was littered with stones and broken glass. This puzzled Arab, and later he asked his father about it: “How can they ask the men to undress in front of the women? They don’t have morals!”

“Humiliation by forced nakedness didn’t just happen to your friends: it is a method used by the Israeli military. When we were in their prisons without any way to defend ourselves, our guards would take sadistic pleasure in seeing us naked, in humiliating us,” Bassam explained.

Arab, being smaller and younger than the other boys, stayed on the bus with the women and children. Then a female soldier got on the bus and demanded: “Bring the dog.” At that point, another soldier boarded the bus with an attack dog and began terrorizing everyone.

It was hours later when Arab was finally able to again communicate with Bassam, who later said, “There are no words for the state I was in during those hours, waiting for his next call and dreading it would not come. Then at 2:30 a.m., a call came.”

“We are at the Moscobiyyeh,” Arab told his father, referring to the main police detention center located by the Russian Compound in Jerusalem.

“Why are you being detained?”

“They didn’t tell us anything.”

“Go up to the solider and tell him, ‘You have to talk to my father, he does not know where I am’.” Arab replied that he was scared to do so; they’d already beaten

many of the kids there because they had talked, and talking was not allowed. “You are a brave boy, you shouldn’t be scared of the soldier. Talk to him in Hebrew.” Over the phone Bassam could hear Arab go up to the soldier and say, “Please, can you talk to my father?” But the soldier told him to shut his mouth and hang up the phone. “If your father wants to see you, tell him to come here,” he said.

Bassam was beside himself, yelling as loud as he could: “You murderers! Where is my son? Do you want to kill him like you killed his sister?” Bassam told Arab to turn on the speakerphone so the soldier could hear what he was saying.

“Dad, don’t be afraid. I am okay. They are going to let us go in a bit like they said; I’ll talk with you soon.” And he hung up.

The soldiers finally let the group go at 3:00 a.m. Arab arrived home 40 minutes later, exhausted but alive and uninjured. After telling his father the entire story, Arab then asked for something Bassam found very surprising. “I want you to take me with you when you go to one of your lectures in Israel so I can tell the Israelis about the practices of their soldiers on that night.”

“Are you serious?”

Arab has always questioned Bassam’s willingness to talk with Israelis. But he insisted, “They have to know what happened so the parents of those soldiers can forbid their children to act that way toward women and children.”

When I learned of what happened to Arab, I felt a need to relay the entire story to Gila and the children. I couldn’t let my children grow up oblivious to the fact that this kind of injustice is taking place. So during our Friday night family dinner I told them about this and soon we were all crying. Eitan and Doron, who love Bassam dearly, were speechless, and so was I.

Israel has tested men like Khaled, Bassam, and Mazen, and thousands of others, and still they are dedicated to reconciliation. The experiences they have suffered at the hands of Israel are not unusual but rather typical stories of the Palestinians I have met. Yet they do not allow the actions of the Israeli military to get in the way of their important work.

I have returned several times to teach karate in Anata, Ramallah, and Deheishe, and each time, as I look at the children and youth that come to my class, I have a better appreciation for who they are and what they have to go through just in order to survive. The pain I feel when I leave them and travel freely around this country that is at least as much theirs as it is mine—if not more—only grows stronger with each visit.

1

Bassam Aramin, “The Palestinian Bar Mitzvah,” Electronic Intifada, July 21, 2008.

http://electronicintifada.net/content/palestinian-bar-mitzvah/7624

.

Abu Ali Shahin

“What made your father change?”

People constantly ask me what it was that made Matti Peled change from a general who was known for his hawkish views and who demanded war in no uncertain terms, to a man determined and dedicated to achieving peace. His insistence that Israel act decisively against Egypt in 1967 and his call for a preemptive strike were part of his legacy, and his harsh words to the hesitant prime minister in the meeting just prior to the war were never forgotten. But his dedication to peace and reconciliation and his dovish opinions in the late part of his life make it hard to believe that during his military service he contributed significantly to Israel’s military buildup, and indeed in those years he was no liberal dove.

My father had his own way of answering that question in interviews and articles. “When Israel’s strategic objectives called for war, I supported the war, and when peace was possible, I called for peace,” he used to say calmly and then add, “There is no conflict here whatsoever.” It was a rational response befitting him.

It never occurred to me, nor did I ever have reason to believe, that there was one decisive moment or event that affected him enough to change his thinking. He was not like that, affected by emotion. That’s what I thought, at least. So as far as I, or the rest of the family, was concerned there was no need to investigate the issue further or dig deeper to look for his motives.

The weekend after my first stay at Deheishe Refugee Camp to teach karate, I called Jamal to see if he was free the following week. He said there was someone he wanted me to meet in person—a man named Abu Ali Shahin. “He is the man who created the order that guided our life in prison, he was our leader, and he has a lot of respect for your father. In fact, he visited your father’s grave several times, and he wants to meet you.”

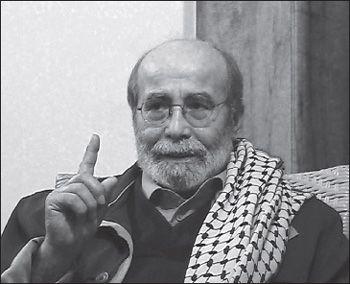

The name didn’t mean anything to me, but I was curious to learn about this man. So the next day I took the bus from East Jerusalem to Ramallah, where I met Jamal. We drove together to pick up a few friends of his, all men who had spent years in Israeli prisons, each with a story that could fill volumes. We arrived at a spacious apartment building in Ramallah, where a diminutive old man with white hair, glasses, and a white beard welcomed us at the door with hugs and kisses and then invited us into his study. I asked if it was all right for me to film him. I was

not sure what he was going to say, but I had a sense it was important so I wanted to record it. He said it was fine and walked out of the room. When he returned, he had a checkered black and white

keffiyeh,

the symbol of

Fatah,

slung over his shoulder. This was Abu Ali Shahin, Fatah commander and leader of the Palestinian political prisoners for more than two decades.

Abu Ali Shahin, Fatah Commander and leader of the Palestinian political prisoners for more than two decades.

“This is the first time I am speaking in Hebrew since 1982,” he said with a smile. And thus began a long, captivating story from a man who at one time was one of Yasser Arafat’s closest assistants and on Israel’s most-wanted list. But more than that, he knew something about my father that I had never heard before.

“In 1948, during the war, my father was killed,” he began.

I later learned that Abu Ali was born in January 1939, so he was not yet 10 when this occurred.

“He commanded the forces that defended our village, Beshshit,

1

and was killed in the battle. After the battle our village was destroyed and we ended up at Rafah Refugee Camp in the Gaza Strip. My father was killed in battle, but war is war, you expect that a man may be killed. But in 1967, just days after the end of the Six-Day War, the Israelis massacred my entire family, killing citizens, not fighters.”

Abu Ali stood up from his chair and began to pour coffee for all of us. He stopped and looked at me. “That is how I know about your father.”

I was puzzled. My father had nothing to do with Gaza in 1967. “How was my father involved?”

“I will get to that in a moment. It was no more than a week after the war when an Israeli army officer showed up in our neighborhood at the Rafah Refugee Camp in Gaza, leading a company of soldiers and a bulldozer. The soldiers told everyone to come out of their homes. The officer inspected everyone and then sent the women and the children who were under 13 years old back home. He took all the men and the boys over 13 to another part of the camp, far enough so the families could not see. Then the soldiers lined everyone up against a wall and shot all of them. When they were done, the officer went one by one and shot each person in the head.”

“How many people were there?”

“More than 30, among them a 13-year-old boy and an 86-year-old man. After he shot them, the bodies were laid in a row on the ground and the bulldozer began driving over them, going back and forth and back and forth until the bodies were unrecognizable.”

“How did you find out?”

“It was in plain view, many people saw it, they saw the bulldozer and they saw the officer go and shoot each person in the head. There are eyewitness accounts.

“My mother ran out when the news reached her, and she was the first to see the men and boys who were killed. She could only tell who was who by the clothes they wore.”

I was barely able to digest all of this and I still did not see how my father could have been connected to any of it.

“Were you in Gaza then?”

“No, I was in the West Bank working undercover. A friend came up to me one day and gave me the bad news.”

“When it was confirmed to me that this really happened, I felt such intense pain that I thought my heart would explode. I knew at that moment that I could never cause anybody to feel such pain. I don’t care if someone is Israeli or Jewish or anything at all, this is such pain that no one should ever have to suffer.”

The atmosphere in the room was growing intense. Abu Ali was sitting comfortably in his chair behind a large desk stacked with books and papers while we were on the edge of our seats. Jamal intervened from time to time to clarify if Abu Ali could not find a word in Hebrew, or offer a translation if he asked for one. But it was clear the entire story was new to all of us.

“Abu Ali, I still don’t see how my father was involved.”

“I am getting to it. Then I was caught and I was interrogated and tortured for five months. During my interrogation I said to my interrogator, a guy named Pinhas, ‘Why do you say we are killers? You are the murderers, not us. Why kill an 86-year-old man? What could he possibly do to you, or a 13-year-old boy?’

“Pinhas took an interest in what I said, and he asked for details. When he came back the next day he took down the names of the people who were killed. Then one day Pinhas came to see me with another officer and said, ‘You see this man, he will make sure someone will look into the massacre of your relatives.’”

“Did he actually use the word massacre?”

I was dubious, so Abu Ali emphasized: “He used the word

mas-sa-cre!

”

“It wasn’t until many years later, 1979, that I learned this officer worked with your father, and I learned what your father did. I was at Shata Prison at the time, and I was talking with an officer from the Shabak [the Israeli General Security Service, or GSS], and he was the first one to tell me that General Peled heard how my family was murdered in Rafah and he went to see for himself. Later I had this confirmed by people in Rafah. Matti Peled came to the camp in person.”

I was hearing all of this for the very first time and the entire thing physically moved me. I looked around at the bookshelves to ease some of the tension. They were stacked with books and binders and I remember thinking that this reminded me of the study of a university professor. Clearly Abu Ali was an intellectual of sorts and had a solid political ideology that was firmly based on principle. But why did my father take such an interest in this particular story? To that I could find no answer, other than it was brought to his attention, and he wanted to see with his own eyes what really happened.

There was more.

“Everyone in Rafah talked about the fact that Matti Peled, one of the greatest officers of the Israeli army, a general that was highly respected, straight as an arrow, the man who was military governor of Gaza, came in person, he even drove himself, and visited the homes of the victims. Your father visited my family’s home, he spoke to the adults and he consoled the children. People commented how disturbed he was when they took him to see the spot where the massacre took place. Your father also wrote a report to Yitzhak Rabin and Haim Bar-Lev, but they did nothing.”

Abu Ali paused and sipped his coffee. He had transported himself, and us with him, to that time and place. What I wouldn’t give to have been in my father’s office when he heard of this and decided to go to Gaza to see for himself. If I could have been beside him as he reached Gaza and began looking around. He spoke Arabic fluently by then so he did not need the help of an interpreter. He was not naïve, and it surely did not surprise him to see that officers and soldiers were capable of atrocities. I remembered that in his Gaza Report, at the end of his tenure as military governor, he wrote of the lawlessness with which soldiers had conducted themselves before he took command.

“It became known that this changed him from a militant man to a man dedicated to peace. I felt your father was with us and that washed away the anger in my heart completely. Completely!”

I had learned to subdue my feelings well enough so as not to show emotion, but this man, this Palestinian commander, hero, and patriot, was talking about my father, General Matti Peled, who for all practical purposes was his sworn enemy. In fact, this man was for many years close to being enemy number one. This was much more than I had ever heard anyone speak about my father, and it was all said with such respect and regard for him.

Abu Ali then looked at Jamal and the other Palestinians and spoke to them in Arabic. When he was done, I said, “Immediately after the war, while still in uniform, my father said that Israel must recognize the rights of the Palestinian people. He said that if we don’t do this, the Israeli army would become an occupation army and would resort to brutal means to enforce the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian people. He said this while still in uniform, and he never stopped saying it and advocating for Palestinian rights till he died.”

Jamal and the others looked at me, and Jamal said, “That is exactly what Abu Ali just said to us in Arabic.”

I had read about this statement, and I know it was said in a meeting of the IDF general staff right after the war, but now I was wondering whether or not this was after he saw what he saw in Gaza. I read what he said over and over: “If we keep these lands, popular resistance to the occupation is sure to arise, and Israel’s army would be used to quell that resistance, with disastrous and demoralizing results.” In light of what Abu Ali was telling me, my father’s words seem almost prophetic. He was always concerned for the moral fabric of Israeli society and Israeli soldiers. Had he already seen the first signs of brutality and therefore said these things? There was no way for me to find out.

We were all silent for several minutes when Umm Ali, Abu Ali’s wife, called us for lunch. We were joined by the rest of his family and friends to a feast of lamb meat, which Abu Ali served us with his bare hands, along with rice and yoghurt. We ate together and then sat in his living room with coffee and fruit. I noticed a larger-than-life tapestry of Yasser Arafat hanging on the wall and next to him portraits of the poet Mahmoud Darwish and Che Guevara.

I was tired, but I wanted to know more. I particularly wanted to know more about Abu Ali’s experiences in prison. Jamal told me that the life of prisoners, their routines of study and political activities, were established largely by Abu Ali. How does a man denied everything in the world that I take for granted not only survive and function, but also find the inner strength to continue fighting and contributing to the welfare of others? He had built an entire movement that impacted thousands of people.

What Jamal told me earlier was also corroborated by Israeli sociologist Dr. Maya Rosenfeld:

The formative nature of the ‘prison years’ in terms of the contribution to the political education and maturation of the individual, is traced back to the process by which

Palestinian prisoners succeeded in organizing themselves inside Israeli prisons and building what they referred to as an ‘internal order’

(“Nitham idakhili”).

2

Dr. Rosenfeld also writes: “It is rare to find a family in the West Bank or in the Gaza Strip that has not experienced the incarceration of at least one of its male members.”

Clearly this is an issue that defines Palestinian society much more than is otherwise known or appreciated. And this man, with whom I just spent almost an entire day, was behind this order that turned the years in prison that so many young Palestinians had to endure into a meaningful, indeed an educational, experience. So after lunch, I asked Abu Ali to carry on with his story about his life and his work in prison.