The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ (51 page)

Read The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ Online

Authors: David Shenk

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

An excerpt from

The Myth of Ability

demonstrates Mighton’s approach:

F-1 Counting

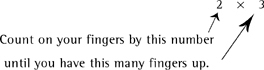

First check whether your student can count on one hand by twos, threes, and fives. If they can’t, you will have to teach them. I’ve found the best way to do this is to draw a hand like this:

Courtesy of Hadel Studio

Have your student practice for a minute or two with the diagram, then without. When your student can count by twos, threes, and fives, teach them to multiply using their fingers, as follows:

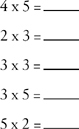

The number you reach is the answer.

Give your student practice with questions like:

Point out that 2 × 3 means: add three, two times (that’s what you are doing as you count up on your fingers). Don’t belabour this point, though—you can explain it in more depth when your student is further into the units. (Mighton,

The Myth of Ability

, pp. 64–65.)

“With proper teaching and minimal tutorial support

”:

Mighton,

The Myth of Ability

, p. 21.

Mighton does not claim his particular teaching method as the only approach, or even the best

:

Mighton,

The Myth of Ability

, p. 27.

John Mighton is also an actor who played a prominent role in the movie

John Mighton is also an actor who played a prominent role in the movie

Good Will Hunting

. The irony is that the message of the movie—brilliance is innate—runs counter to his marvelous work at JUMP.

In fact, countless students fall behind in math and other subjects for exactly the same reason others generally hate to compete directly in any field

:

Tauer and Harackiewicz, “Winning isn’t everything,” pp. 209–38; Durik and Harackiewicz, “Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation,” pp. 378–85.

“I wasn’t quite suited for the educational system,” Bruce Springsteen has said

:

Interview conducted by Ted Koppel, ABC’s

Nightline Up Close

.

“If non-linear leaps in intelligence and ability are possible

”:

Mighton,

The Myth of Ability

, p. 19.

“Man—every man—is an end in himself, not the means to the ends of others,” Ayn Rand wrote

:

Rand, “Introducing Objectivism.”

“Kenyan coaches can afford to push their athletes to the most extreme boundaries

”:

Wolff, “No Finish Line.”

CHAPTER 10:

GENES 2.1—HOW TO IMPROVE YOUR GENES

PRIMARY SOURCES

Harper, Lawrence V. “Epigenetic inheritance and the intergenerational transfer of experience.”

Psychological Bulletin

131, no. 3 (2005): 340–60.

Jablonka, Eva, and Marion J. Lamb.

Evolution in Four Dimensions

. MIT Press, 2005.

Morgan, Hugh D., Heidi G. E. Sutherland, David I. K. Martin, and Emma Whitelaw. “Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse.”

Nature Genetics

23 (1999): 314–18.

Watters, Ethan. “DNA Is Not Destiny.” Published on the

Discover

Web site, November 22, 2006. (A superb piece, without which I would have been unable to write this chapter.)

CHAPTER NOTES

An important corrective of the Lamarck legacy, from Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb:

This often repeated version of the history of evolutionary ideas is wrong in many respects: it is wrong in making Lamarck’s ideas seem so simplistic, wrong in implying that Lamarck invented the idea that acquired characteristics are inherited, wrong in not recognizing that use and disuse had a place in Darwin’s thinking too, and wrong to suggest that the theory of natural selection displaced the inheritance of acquired characters from the mainstream of evolutionary thought. The truth is that Lamarck’s theory was quite sophisticated, encompassing much more than the inheritance of acquired characters. Moreover, Lamarck did not invent the idea that acquired characters can be inherited—almost all biologists believed this at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and many still believed it at its end. (Jablonka and Lamb,

Evolution in Four Dimensions

, p. 13; see also Ghiselin, “The Imaginary Lamarck: A Look at Bogus ‘History’ in Schoolbooks.”)

Lamarck wrote:

All the acquisitions or losses wrought by nature on individuals, through the influence of the environment in which their race has long been placed, and hence through the influence of the predominant use or permanent disuse of any organ; all these are preserved by reproduction to the new individuals which arise, provided that the acquired modifications are common to both sexes, or at least to the individuals which produce the young. (Lamarck,

Zoological Philosophy

, p. 113.)

Lamarck wrote:

It is interesting to observe the result of habit in the peculiar shape and size of the giraffe: this animal, the tallest of the mammals, is known to live in the interior of Africa in places where the soil is nearly always arid and barren, so that it is obliged to browse on the leaves of trees and to make constant efforts

to reach them. From this habit long maintained in all its race, it has resulted that the animal’s forelegs have become longer than its hind-legs, and that its neck is lengthened to such a degree that the giraffe, without standing up on its hind-legs, attains a height of six meters. (Lamarck,

Philosophie Zoologique

, as quoted in Gould,

The Structure of Evolutionary Theory

, p. 188.)

Drawing of Giraffe in a “classic” feeding position, extending its neck, head, and tongue to reach the leaves of an Acacia tree. Tsavo National Park, Kenya:

Drawing by C. Holdrege. (Holdrege,

In Context

#10, pp. 14–19)

Actually, what the general public still refers to as our “Darwinian” understanding of evolution is more properly called the “modern evolutionary synthesis,” a melding of Darwin’s ideas with later genetics discoveries.

Actually, what the general public still refers to as our “Darwinian” understanding of evolution is more properly called the “modern evolutionary synthesis,” a melding of Darwin’s ideas with later genetics discoveries.

Here is a nice synopsis of the modern evolutionary synthesis, from Douglas J. Futuyma:

The major tenets of the evolutionary synthesis, then, were that populations contain genetic variation that arises by random (i.e. not adaptively directed) mutation and recombination; that populations evolve by changes in gene frequency brought about by random genetic drift, gene flow, and especially natural selection; that most adaptive genetic variants have individually slight phenotypic effects so that phenotypic changes are gradual (although some alleles with discrete effects may be advantageous, as in certain color polymorphisms); that diversification comes about by speciation, which normally entails the gradual evolution of reproductive isolation among populations; and that these processes, continued for sufficiently long, give rise to changes of such great magnitude as to warrant the designation of higher taxonomic levels (genera, families, and so forth). (Futuyma,

Evolutionary Biology

, p. 12.)

Pictures of Toadflax flowers

:

Emil Nilsson. Used by permission.

There

was

a difference between the two flowers on their respective epigenomes

:

Jablonka and Lamb,

Evolution in Four Dimensions

, p. 42.

DNA is famously wound together in a double-helix strand

.

Diameter of DNA is about 20 angstroms (1 angstrom = 1 × 10

–10

meters).

These histones protect the DNA and keep it compact

.

They also serve as a mediator for gene expression, telling genes when to turn on and off. It’s been known for many years that this epigenome (“epi-” is a Latin prefix for “above” or “outside”) can be altered by the environment and is therefore an important mechanism for gene-environment interaction.