The German War (36 page)

Authors: Nicholas Stargardt

Farnbacher realised that he himself had become ‘hard and ruthless’. With its double connotations of ‘hardness’ and ‘toughness’,

Härte

had long been a male, military virtue in Germany. Hitler Youths were taught to strive for it, and soldiers sought to master it during their months of basic training and first ‘baptisms’ of fire. During the final, difficult weeks of the retreat from Moscow, the 4th Panzer Division’s chief doctor noted with approval how the men had learned to be ‘hard on themselves’. The word was now acquiring something of the meaning Hitler gave it in closed briefing sessions, when he used ‘hard’ as a metaphor for genocidal measures. Hinting at the process of self-brutalisation, ‘hard’ and ‘harsh’ increasingly complemented the sacralising language of heroic self-sacrifice used in both official and private accounts.

16

Härte

had long been a male, military virtue in Germany. Hitler Youths were taught to strive for it, and soldiers sought to master it during their months of basic training and first ‘baptisms’ of fire. During the final, difficult weeks of the retreat from Moscow, the 4th Panzer Division’s chief doctor noted with approval how the men had learned to be ‘hard on themselves’. The word was now acquiring something of the meaning Hitler gave it in closed briefing sessions, when he used ‘hard’ as a metaphor for genocidal measures. Hinting at the process of self-brutalisation, ‘hard’ and ‘harsh’ increasingly complemented the sacralising language of heroic self-sacrifice used in both official and private accounts.

16

Near the coast of the Gulf of Finland, Albert Joos chronicled a similar process of ‘hardening’, as he and his comrades weathered the winter war of position. With little protection as the temperature fell to −30 °C in the second half of December, Joos had begun to suffer terrible headaches. All month they continued building out their positions at night and enduring machine-gun and mortar attacks during the day. As was his wont, Albert Joos spent New Year reviewing not just the last year, but his ‘whole past life’ in order to perceive ‘the Lord’s unlimited power and providence out of this . . . confusion of life’. He affirmed his ‘unshakeable faith in the Lord and with it the trust that He will also direct things for my best in this year. With this trust I will remain upright in this year too and master my life with a sense of duty.’ His patriotic fervour may have been more Catholic than National Socialist, but his sense of personal duty was at least as keen.

17

17

In January, things got worse. Soviet artillery began firing shrapnel at their trenches and, as the temperature plummeted to −40 °C, the gunners aimed at the German field kitchens, depriving the soldiers of warm food. Their own sentries had to be relieved every hour because of the extreme cold and when Joos, now an acting sergeant, went on his rounds his earmuffs froze to his skin. They had to use hand grenades to excavate the frozen soil. After each snowstorm, as drifts filled the German trenches, the Red Army men attacked in massed waves, only to be mown down by the German machine guns. Without access to a priest or religious services, the farmer’s son confessed to his diary in order ‘to keep a balance of my life, to consider what is right and wrong and to keep perspective’. Fumbling in the cold to get the words down, Albert Joos concluded, ‘Very rarely are people subjected in their lives to such brutalisation

[Verrohung]

and forced to live in such primitive conditions as in the trenches.’ He did not exclude himself from this process. Trench warfare had also schooled him to focus narrowly on survival and killing: ‘the continual lying in wait for the enemy, in order to do him in at any opportunity, that lets one become properly harsh [roh].’ Existential fear now turned Nazi propaganda about Jewish-Bolshevism, treacherous civilians and dangerous partisans into common sense. However nagging the lingering scruples of individuals, who recognised with distaste how ‘hard’, ‘harsh’, ‘brutal’ and ‘coarse’ they themselves had become, the collective self-transformation of the eastern front was complete.

18

[Verrohung]

and forced to live in such primitive conditions as in the trenches.’ He did not exclude himself from this process. Trench warfare had also schooled him to focus narrowly on survival and killing: ‘the continual lying in wait for the enemy, in order to do him in at any opportunity, that lets one become properly harsh [roh].’ Existential fear now turned Nazi propaganda about Jewish-Bolshevism, treacherous civilians and dangerous partisans into common sense. However nagging the lingering scruples of individuals, who recognised with distaste how ‘hard’, ‘harsh’, ‘brutal’ and ‘coarse’ they themselves had become, the collective self-transformation of the eastern front was complete.

18

Hans Albring survived the winter months in the small town of Velizh, in the rear of Army Group Centre. Coming under attack in late January 1942, here the Germans held out for eight weeks in fearful conditions. Unwashed, lice-ridden and hungry, Hans emerged from the ordeal convinced that ‘comparison with the Apocalypse is not too far-fetched’. But he was able to tell his friend Eugen Altrogge on 21 March that ‘what I have gained in experience is greater than what I lost’. By mid-April, two weeks after the Red Army had finally stopped its attacks, Hans seized eagerly on a letter from one of his Catholic mentors in Münster, quoting it at length to Eugen, in support of the view he had formed: ‘“And, who knows, perhaps this is the metaphysical meaning of the war, that a new and true image of humanity is arising in us, after we have followed a false, and increasingly distorting, image of humanity for so many hundreds of years.”’

19

19

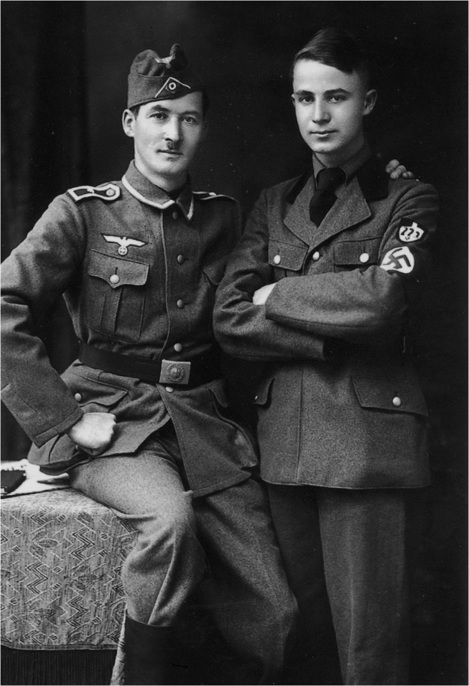

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

On the eve: Irene Reitz and Ernst Guicking.

Fathers and sons: August and Karl-Christoph Töpperwien.

Fathers and sons: Wilm and Helmut Hosenfeld.

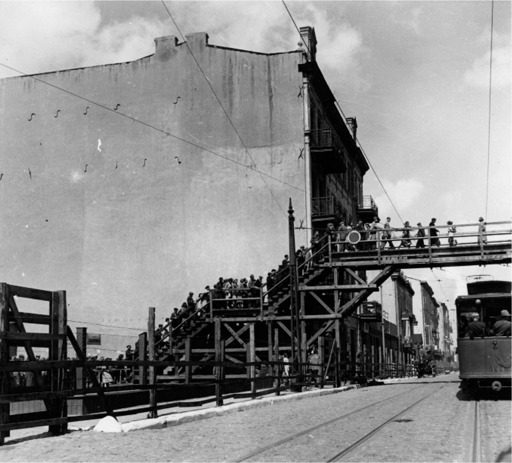

POLAND, SEPTEMBER 1939

The Polish view: 10-year-old Kazimiera Mika finds her older sister, killed by a German plane while digging potatoes in Warsaw.

The German view, from the nose of a Heinkel He 111 P bomber.

FOR AND AGAINST

Frieda and Josef Rimpl’s wedding: he was executed for conscientious objection in December 1939.

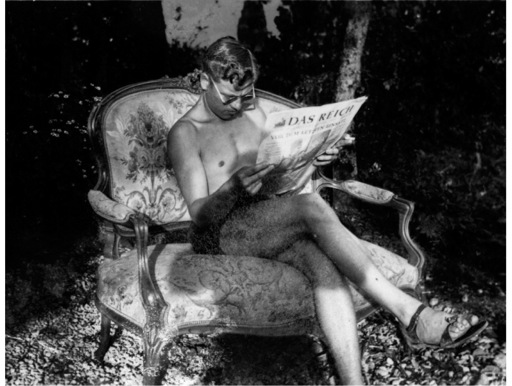

Ernst Guicking reading

Das Reich

in France.

Das Reich

in France.

LISELOTTE PURPER’S WAR

Practising air raid defence: Berlin, 1939.

Liselotte Purper with her Rolleiflex.

Other books

New Atlantis by Le Guin, Ursula K.

The Ghost at the Table: A Novel by Suzanne Berne

A Heartless Design by Elizabeth Cole

The Pleasures of Sin by Jessica Trapp

An Inconvenient Trilogy by Audrey Harrison

Alberto's Lost Birthday by Diana Rosie

Tales of the Witch by Angela Zeman

The Wayward Alpha (Paranormal Werewolf Shifter Romance) by Wilson, Joanna

Magnificent Joe by James Wheatley