The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall (13 page)

Read The Ghost of Crutchfield Hall Online

Authors: Mary Downing Hahn

As winter waned and the days grew longer and warmer, Miss Amelia encouraged James and me to spend more time out-of-doors. Impressed with our drawing skills, she urged us to try what she called

plein air

exercises.

“Find a tree, a building, a view,” she told us, “and sit outside and sketch.”

At first we were satisfied to draw the garden, the terrace, the fine old oaks lining the drive, and the distant hills. There seemed no end of interesting views to capture. Old stone walls, outbuildings, Spratt at work with hoe or shovel, Cat sleeping in the sun.

One afternoon, I was hard at work drawing the cat's ears, a very difficult thing to get right. Suddenly James sighed in exasperation and threw his pencil down.

“I'm tired of drawing that cat,” he said.

“Draw something else then,” I suggested. I was vexed with the cat myself. He kept changing his position, which meant everything I'd drawn before was wrong, including his dratted ears.

James looked around and frowned. “I don't see anything I want to draw.”

“We could go for a walk,” I said. “Maybe we'll find something new.”

Gathering our pencils and sketchpads, we headed for the fields beyond the stone wall. A narrow public walkway led over a hill.

“I've been this way before,” I told James.

“When?”

“I walked up the drive the day I came to Crutchfield Hall, so it couldn't have been then.” I looked around, beginning to remember. “There was snow on the ground, and I was cold. The wind blew in my face. I was running.”

“Were you alone?” James asked, suddenly serious.

I shook my head, remembering everything. “I was with Sophia. She took me to the churchyard to see her headstone. It was the day she made you climb out on the roof. Her death-day.”

“Poor Sophia,” James whispered. “She's been gone all this time, and we haven't visited her grave once.”

“Do you think we should?” Truthfully, I wasn't at all certain I wanted to be that near Sophia. Suppose we disturbed her somehow? Suppose she came back?

He looked at me. “She's all alone there.”

Reluctantly, I followed James up the hill, through the gate, and down the road to the village. It was a weekday, so not many people were about. A woman hung laundry in her yard. A small child pulled an even smaller child in a wagon. A horse trotted by hauling a carriage at a good clip. I glimpsed a bonneted head inside. A dog sleeping in the middle of the road got up and moved slowly out of the horse's way.

Under an almost cloudless sky, the old stone church dozed in the shade of trees. How different it had looked on that snowy day last winter, the stones dark and imposing, the trees bare, the wind howling. Now the headstones rose from freshly cut grass, tilting this way and that, some mossy with age, others newer. A flock of crows strutted among the stones, pecking in the grass. From the church roof, a line of wood pigeons watched us. Their melancholy voices blended well with the setting.

Hand in hand, James and I walked along gravel paths looking for Sophia's grave. Then we saw it. Her tilted stone cast a shadow across the grass.

In a low voice, James read his sister's inscription aloud. When he spoke her name, I braced myself, fearing she might rise up before us.

She did not appear. The wood pigeons cooed, a crow called and another answered, a breeze rustled the leaves over our heads, but Sophia remained silent.

“Do you know what today is?” James asked.

I thought for a moment. “It's the twenty-seventh of July,” I whispered. “Half a year since we last saw her.”

James held my hand tighter. “Do you think she'll come back again?”

“I hope not,” I said, but I couldn't hide the uncertainty in my voice.

“Perhaps her spirit isn't here anymore,” James said. “Perhaps she's with Mama and Papa.” He looked at me as if for confirmation.

I nodded, hoping it was true.

“Maybe she's not angry now,” James said softly. “Maybe she's not jealous. Maybe she knows now that she can't change her fate.”

I nodded again, still hoping it was true, still not sure. Sophia was not the sort who would accept what could not be changed.

“I miss her sometimes,” James said. “She wasn't always mean, you know. She could be quite nice when she wanted to be.”

“I'm glad to hear that.” I stared at the gravestone, warmed by the afternoon sun. It was almost impossible to picture Sophia lying peacefully six feet below us, tucked into her grave as snugly as a child is tucked into bed. All that anger, all that energyâwhere had it gone?

For a moment, the grass over Sophia moved as if something deep down below stirred in its sleep. With a flash of terror, I remembered what she'd told me about crawling from her grave six months after her death. I backed away, almost tripping on a tree root.

Six months,

I thought.

Six months today.

Unaware of my distress, James contemplated Sophia's headstone. “Can we sit here for a while?” he asked. “I have a mind to draw a picture of my sister's grave.”

I wanted to say no. I did not like graveyards, especially this one, but he'd already sat down and spread his art supplies on the grass.

While James sketched, I resisted the urge to seize his arm and pull him away. Perhaps I was being overly cautious, but I did not dare risk disturbing Sophia. Anything might rouse herâthe scritch-scratch of James's pencil, the sad calls of the pigeons, the wind in the grass, even the soft sound of my breath or the solemn beat of my heart.

“James,” I whispered. “We should go home. Uncle will wonder where we've gone.”

He looked at me and smiled. “All right. I've finished my drawing.”

As James gathered his things, I glanced at his picture. He'd drawn not only the tombstone, but his sister as well, standing in its shadow, blending in with the trees behind her. I couldn't be sure if she was smiling or frowning.

“Why is Sophia in the picture?” I asked him.

“She's not,” he said.

I held the picture up and pointed to the indistinct image. “Who's this, then?”

James stared at what he'd drawn and shook his head. “I didn't put her thereâI swear I didn't.” He began to cry. “I was just sketching the trees. That's all. How did she get in my picture? Who drew her?”

I put my arms around him and stared over his head at Sophia's grave. Once again the grass stirred. A wind rose and rustled the leaves. For a moment, I thought I heard someone laughing at us.

Dropping the picture, I took James's hand. He looked at me, his face pale with fear. “Is she coming back?” he whispered.

I stared at the shadowy place under the tree, not sure whether she was there or not. “Even if she does come back,” I said, “she can't hurt us. What's done is done. No matter how often she tries to change her fate, she will fail.”

James tightened his grip on my hand. “It's very sad,” he whispered. “I feel sorry for her.”

“Better to feel sorry than frightened.” Turning back to the shadowy place under the tree, I said loudly, “We are stronger than you are, Sophia. You cannot harm us, you cannot frighten us, you cannot make us obey you anymore.”

“Leave us alone!” James cried. “Please, please, Sophia, rest in peace.”

The wind rustled the leaves and blew through the grass on Sophia's grave. Its sound was as low and sad as the pigeons calling to one another on the church roof.

Wordlessly, James and I left the churchyard. Over our heads, the sky was a clear blue dome, and the road lay before us, dappled with sunshine and shadow. When we got home, Mrs. Dawson would have tea and cake ready for us. Later, we'd take our books outside and read in the garden or play croquet with Miss Amelia.

I looked over my shoulder. The old church spire rose above the trees. I could no longer see the graves, but I knew they were there, dozing in the sunlight, tilting this way and that, some cradled in tree roots, some almost hidden in tangles of weeds and wildflowers. I hoped Sophia had heard what we'd said and would remain where we'd left her, at peace among the dead.

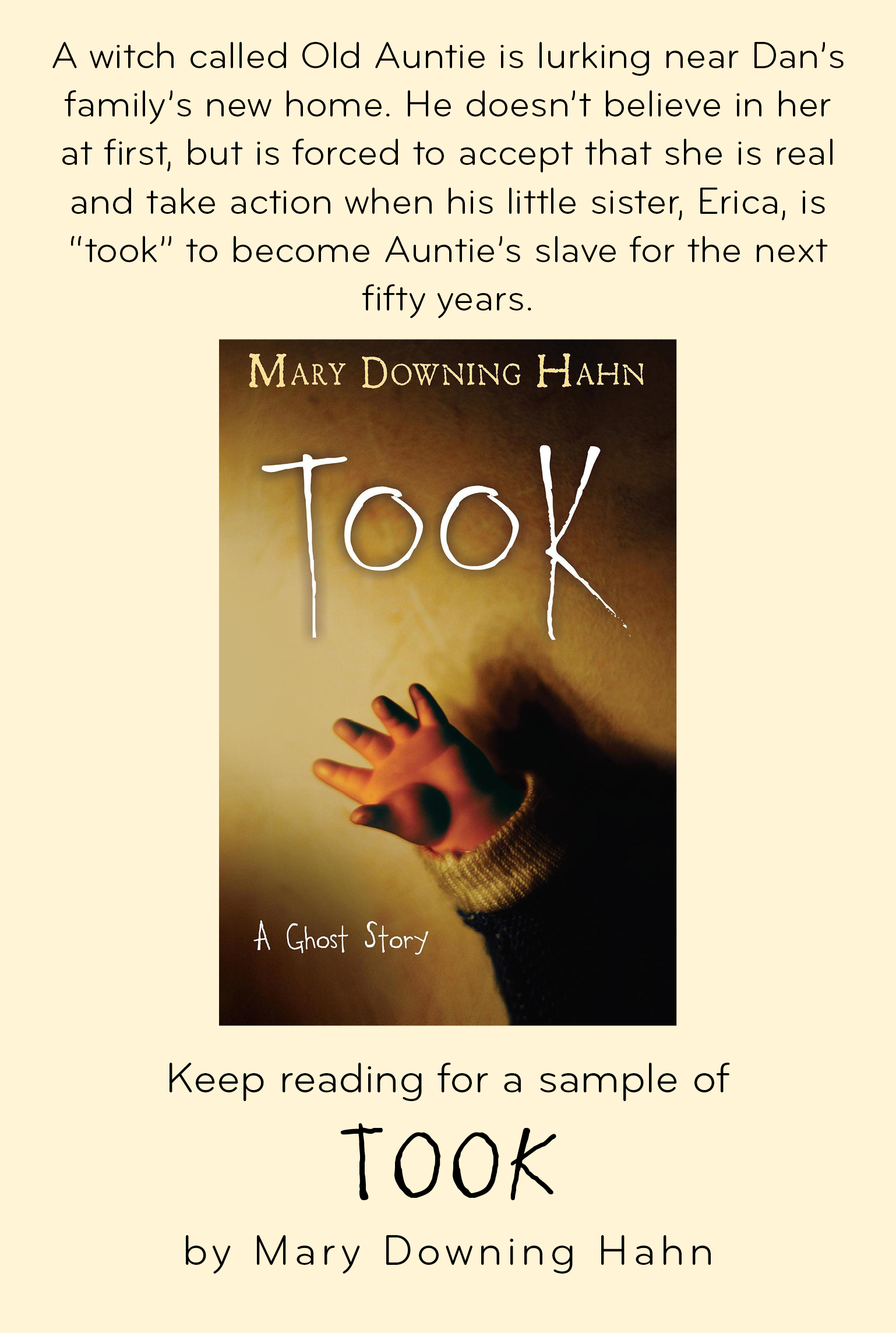

The old woman stands on the hilltop, just on the edge of the woods, well hidden from the farmhouse below. Two men and a woman are getting out of a car that has a sign for Jack Lingo Realty painted on the side. The old woman has seen plenty of Realtors in her time. She doesn't know this one, but she remembers his pa, old Jack Lingo, and

his

pa, Edward, and the one afore him, back and back through the years to the first Lingo ever to settle in this valley and take up the buying and selling of houses.

Though young Lingo doesn't know it, Auntie is helping him sell that house to the man and the woman in the only way she knowsâmuttering and humming and moving her hands this way and that way, weaving spells in the air, sending messages as she's always done. Messages that make folks need things not worth needing. Dangerous things. Things they regret getting.

You might wonder why Auntie wants this man and woman to buy the house. Truth to tell, she doesn't give a hoot about them. They're ignorant fools, but they have something she wants, and she aims to get it. It's almost time for the change, and they've come on schedule, just as she'd known they would.

“New for old,” she chants to herself. “Strong for weak, healthy for sickly, pretty for ugly.”

When the man and the woman follow young Lingo into the old Estes house, Auntie sways back and forth, grinning and rubbing her dry, bony hands together. Her skirt blows in the wind, and long strands of white hair whip around her face. With a little hop and a jig, she turns to something hidden in the trees behind her. “Won't be long now, my boy. We'll get rid of the old pet and get us a new one to raise up.”

Though he stays out of sight, her companion makes a noise like a hog when it's hungryâa squealing sort of snort that might be a laugh, or it might be something else altogether.

Auntie gazes down at the rundown farmhouse and outbuildings, the overgrown fields, the woods creeping closer year by year. From the hill, she can see the missing shingles in the roof, the warped boards riddled with termites and dry rot, the cracks in the chimney.

Almost fifty years have passed since the Estes family left the place. Nobody has lived there since then. Local folk avoid the place. They scare their children with stories about the girl, the one before her, and the one before her, back and back to the very first girl. Fear keeps them out of the woods and away from the cabin on Brewster's Hill. Those children know all about Auntie and her companion.

But newcomers always show up, city people who've never heard the stories. If the valley folk try to warn them, they scoff and laugh and call the stories superstitious nonsense. They come from places where lights burn all night. They don't heed the dark and what hides there.

It all works to Auntie's advantage.

Down below, a door opens, and Auntie watches young Lingo lead the man and woman outside. Even though they speak softly, Auntie hears every word. They aim to buy that tumbledown wreck of a house, fix it up, and live there with their children, a boy and a girl, they tell him. It's just what they wantâa chance to get away from their old life and start anew in the country. They'll get some chickens, they say, a couple of goats, maybe even a cow or a sheep. They'll plant a garden, grow their own food.

The man and the woman get into the Realtor's car, laughing, excited. Auntie spits into the dirt. Fools. They'll find out soon enough.

She listens to the car's engine until she can't hear it anymore. Then she snaps her fingers and does another jig. “It's falling into place just like I predicted, dear boy, but don't you say a word to her back at the cottage. She ain't to know till it happens.”

Her companion snorts and squeals, and the two of them disappear into the dark woods.

To wait.

ne

It was a long drive from Fairfield, Connecticut, to Woodville, West Virginiaâtwo days, with an overnight stay in Maryland. My sister, Erica, and I were sick of the back seat, sick of each other, and mad at our parents for making us leave our home, our school, and our friends.

Had they asked us how we felt about moving? Of course not. They've never been the kind of parents who ask if you want to drink your milk from the red glass or the blue glass. They just hand you a glass, and that's that. Milk tastes the same whether the glass is blue or red or purple.

Going to West Virginia was a big thing, something we should have had a say in, but no. They left us with a neighbor, drove down there, found a house they liked, and bought it. Just like that.

They were the grownups, the adults, the parents. They were in charge. They made the decisions.

In all fairness, they had a reason for what they did. Dad worked for a big corporation. He earned a big salary. We had a big house, two big cars, and all sorts of other big stuffâexpensive stuff. Erica and I went to private school. Mom didn't work. She was what's called a soccer mom, driving me and Erica and our friends to games and clubs and the country club pool. She and Dad played golf. They were planning to buy a sailboat.