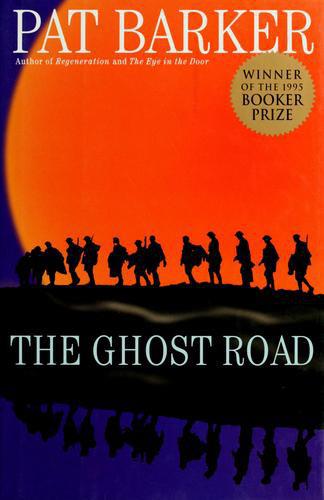

The Ghost Road

Authors: Pat Barker

For David

Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living; but the dead

Returning lightly dance

'Roads',

Edward Thomas

PART

ONE

CHAPTER ONE

In deck-chairs all along the front the bald pink knees

of Bradford businessmen nuzzled the sun.

Billy Prior leant on the sea-wall. Ten or twelve feet

below him a family was gathering its things together for the trek back to

boarding-house or railway station. A fat, middle-aged woman, swollen feet

bulging over lace-up shoes, a man with a lobster-coloured tonsure—my God, he'd

be regretting it tomorrow—and a small child, a boy, being towelled dry by a

young woman. His little tassel wobbled as he stood, square-mouthed with pain,

howling,

'Ma

-a-am.' Wet sand was the problem. It

always was,

Prior

remembered. However carefully you

tiptoed back from that final paddle, your legs got coated all over again, and

the towel always hurt.

The child wriggled and his mother slapped him hard,

leaving red prints on his chubby buttocks. He stopped screaming, gulped with

shock, then settled down to a persistent grizzle. The older woman protested,

'Hey, our Louie, there's no need for that.' She grabbed the towel. 'C'mon, give

it here, you've no bloody patience, you.'

The girl—but she was not a girl, she was a woman of

twenty-five or twenty-six, perhaps-retreated, resentful but also relieved. You

could see her problem. Married, but the war, whether by widowing her or simply

by taking her husband away, had reduced her to a position of tutelage in her

mother's house, and then what was the point? Hot spunk trickling down the

thigh, the months of heaviness, the child born on a gush of blood—if all that

didn't entitle you to the status and independence of a woman, what did? Oh, and

she'd be frustrated too. Her old single bed

back,

or

perhaps a double bed with the child, listening to snores and creaks and farts

from her parents' bed on the other side of the wall.

She was scrabbling in her handbag, dislodging bus

tickets, comb, purse, producing, finally, a packet of Woodbines. She let the

cigarette dangle wetly from her lower lip while she groped for the matches. Her

lips were plump, a pale salmon pink at the centre, darkening to brownish red at

the edges. She glanced up, caught him looking at her, and flushed, not with

pleasure—his lust was too blatant to be flattering— but drawn by it,

nevertheless, into the memory of her unencumbered girlhood.

Her mother was helping the little boy step into his

drawers, his hand a dimpled starfish on her broad shoulder. The flare of the

match caught her attention. Tor God's sake, Louie,' she snapped. 'If you could

only see how common you look...'

Louie's gaze hadn't moved. Her mother turned and

squinted up into the sun, seeing the characteristic silhouette that said

'officer'. 'Look for the thin knees,' German snipers were told, but where they

saw prey this woman saw a predator. If he'd been a private she'd have asked him

what the bloody hell he thought he was gawping at. As it was, she said, 'Nice

weather we're having, sir.'

Prior smiled, amused,

recognizing

his mother's speech, the accent of working-class gentility. 'Let's hope it

lasts.'

He touched his cap and withdrew, thinking, as he

strolled off, that the girl was neither a widow nor married. The way the

mother's voice had cracked with panic over that word 'common' said it all.

Louie's knees were by no means glued together, even

after the child. And her mother was absolutely

right,

with that fag stuck in her mouth she did look common.

Gloriously,

devastatingly,

fuckably

common.

He ought to be getting back to barracks. He had his

medical in less than an hour, and it certainly wouldn't do to arrive gasping.

He had no business to be drifting along the front looking at girls. But he

looked anyway, hoarding golden fuzz on a bare arm, the bluish shadow between

breasts thrust together by stays, breathing in lavender sharpened by sweat.

The blare of music inside the fairground drew him to

stand in the entrance. So far today the only young men he'd seen had been in

uniform, but here were men as young as

himself

in

civilian dress.

Munitions workers.

One of them was

chatting to a young girl with bright yellow skin. He felt the automatic flow of

bile begin and turned away, forcing himself to contemplate the bald grass. A

child, holding a stick of candy-floss, turned to watch him, attracted to the

man who stood so still among all the swirl and dazzle. He caught her looking at

him and smiled, remembering the soft cotton-wool sweetness of candy-floss that

turned to clag on the roof of your mouth. She bridled and turned away,

clutching her mother's skirt.

Very wise.

As he walked on, his smile faded.

He

could have been a munitions worker, he thought.

Kept out of

danger.

Lined his pockets.

His father would

have wangled him a place in a nice safe reserved occupation, and would not have

despised him for it either, unlike many fathers. The weedy little runt would at

least have been behaving like a

sensible

weedy little

runt, refusing to fight in 'the bosses' war'.

But he'd never seriously considered doing that.

Why not?

he

wondered now.

Because I don't want to be one of

them

, he thought,

remembering a munitions worker's hand patting a girl's bottom as he helped her

into the swing-boat. Not

duty, not patriotism, not fear

of what other people would think, certainly that.

No, a kind

of... fastidiousness.

Once, as a small boy, he'd slipped chewed-up

pieces of fatty mutton into the pocket of his

because he couldn't bring himself to swallow them, and

his father, when the crime came to light, had said, in tones of ringing

disgust, That bairn's too fussy to live.' Too fussy to live,

Prior

thought. There you are, nowhere near France and an epitaph already. The thought

cheered him up enormously.

By now he was walking up the hill towards the

barracks, a chest-tightening climb, but he was managing it well. His asthma was

good at the moment, better than it had been for months. All the same it might

be as well to sit quietly somewhere for a few minutes before he went into the

examination room. In the end all he could do was to turn up in a reasonable

state, and answer the questions honestly (or at least tell no lies that were

likely to be found out). The decision would be taken by other people. It always

was.

Though he had managed to take

one

decision himself.

His thoughts shifted to Charles Manning and the last

evening they'd spent together in London.

—Have you stopped to think what's going to happen if

you re not sent back?

Manning had asked.

Six months, at least six months, probably to the end

of the war, making sure new recruits wash between their toes.

—Might have its moments.

—Doing a hundred and one completely routine jobs, each

of which could be done equally well by somebody else. You'd be much better

working at the Ministry. I can't promise to keep the job open.

—No, thank you, Charles.

No, thank you. He was passing the Clarence Gardens

Hotel where he'd been stationed briefly last winter before the summons to

London came.

Plenty of routine jobs there.

He and

Owen, his fellow nutcase, had arrived on the same day, neither of them

welcomed by the CO. They'd been assigned to 'light duties'. Prior became an

administrative dogsbody, sorting out the battalion's chaotic filing system.

Owen fared yet worse, chivvying the charladies, ordering vegetables, peering

into lavatory bowls in search of unmilitary stains. Mitchell had given them

hell. Prior got him in the mornings when he was

totally

vile, Owen in the

evenings when brandy had mellowed him slightly.

—What do you expect?

Prior said, when Owen complained.

He's lost two sons. And who shows up instead of them?

Couple of twitching Nancy boys from a loony-bin in Scotland.

Silence from Owen.

—That's what he thinks, you know.

As he reached the entrance to the barracks, a squad of

men in singlets and shorts, returning from a cross-country run, overtook him

and he stood back to let them pass. Bare thighs streaked with mud, steam rising

from sweaty chests, glazed eyes, slack mouths, and as they pounded and panted

past, he recognized Owen at the head of the column, turning to wave.

'Good heavens,' Mather said, as

Prior

pulled off his shirt. 'You haven't been getting much outdoor exercise, have

you?'

'I've been working at the Ministry of Munitions.'

Mather was middle aged, furrow-cheeked, sandy-haired,

shrewd

.

'All right, drop your drawers. Bend over.'

They always went for the arse, Prior thought, doing as

he was told. An army marches on its stomach, and hobbles on its haemorrhoids.

He felt gloved fingers on his buttocks, separating them, and thought, Better

men than you have paid for this.

'I see you've got asthma.'

There?

'Yes, sir.'

'Turn round.'

Another unduly intimate gesture.

'Cough.'

Prior cleared his throat.

'I said,

cough'

The

fingers jabbed.

'And again.'

The hand changed sides.

'Again.'

Prior was aware of wheezing as he caught his breath.

'How long?'

Prior looked blank, then stammered.

'S-six

months, sir.'

'Six months? But it says—'

'I mean, the doctor told my mother I had it when I was

six months old, sir.'

'Ah.' Mather turned over a page of the file. 'That

makes more sense.'

'Apparently I couldn't tolerate milk.'

Mather looked up. 'Awkward little bugger, weren't you?

Well, we'd better have a listen.' He reached for his stethoscope and came

towards

Prior

. 'What were you doing at the Ministry of

Munitions?'

'Intelligence, sir.

'Oooh,

very

impressive.

Catch anybody?'

Prior looked bleakly ahead of him. 'Yes.'

'Patrol here caught a German spy on the cliffs.'

Mather snorted, fitting the stethoscope. 'Tickled a local yokel with their

bayonets more like.'

Prior started to say something, but Mather was

listening to his chest. After a few minutes, he straightened up. 'Yes, you have

got a bit of a wheeze.' His attention was caught by the scar on Prior's elbow.

He turned the arm towards him.

'The Somme,'

Prior

said.

'Must've hurt.'

'The expression "funny bone" didn't seem

appropriate at the time.'

Mather went back to the desk, sat down. 'Now let's see

if I've got this straight. You were invalided home with shell-shock. That

right?

April last year?'

'Yes, sir.'

'And you were sent first to Netley and then to

Craiglockhart War Hospital, where you remained till

...

November.' He looked

up. 'I suppose you get a lot of dipsomania, in places like that?

Alcohol

,

man,' he explained, as

Prior

continued to look blank.