The Girl of Ink & Stars (7 page)

Read The Girl of Ink & Stars Online

Authors: Kiran Millwood Hargrave

CHAPTER

TEN

I

t was hushed in the forest. The horse-high bushes stopped sound the way water does, and the torches' light threw everything into shadow. After a couple of the men had drawn swords on nothing more threatening than a branch, Governor Adori ordered them to put out the torches. My eyes quickly adjusted, and I felt safer knowing we could not be seen as easily.

The route was clear â the trampled bushes, leaking pale sap, were the only break in the undergrowth. I imagined Lupe, alone and determined.

I'll show you I'm not rotten

.

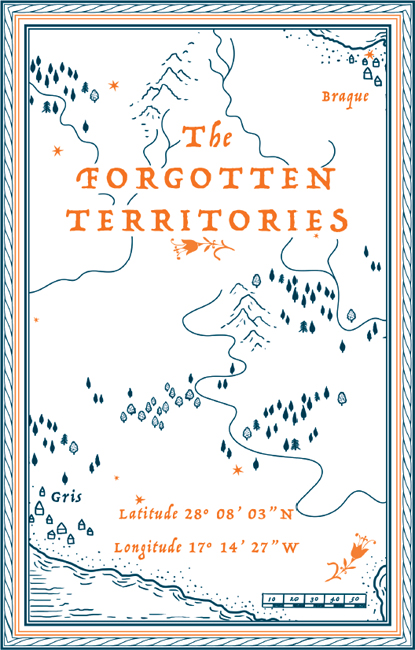

I was not needed to navigate while the path was so obvious, so I took out the compass, peering at it through the gloom. Despite fearing for Lupe, I could not ignore that I was in the Forgotten Territories at last. I would make a map Da would be proud of.

Every hundred strides the horses took, I marked a line on the soft leather pad I held in my palm, and every time the

compass indicated a change in direction I scored under these lines with an arrow showing the new bearings, consulting the stars the way Da taught me. This was map-making at its most basic, but it was clear the others would not stop and wait for me to take more accurate measurements. I would just have to rely on memory when it came to drawing up the map. That was how I did it with Lupe on our treasure hunts through Gromera's narrow streets.

My hand was at my throat before I could stop it, feeling for the locket through my tunic. Marquez narrowed his eyes and I clasped the reins. Maybe it had not been the best idea to bring it with me.

None of us spoke for a while. The Governor's shoulders were set, and he hardly moved with the lilt of his horse. He obviously wanted to go faster, but the darkness and the narrow path made it impossible.

After a few miles the horses started to move more cautiously, shaking their heads and whinnying softly. The men drove them forward, digging the spurs on their stirrups into the animals' sides. My horse stopped completely until Pablo hit it sharply on the hindquarters.

It was a few more miles before any of us realized what was wrong. Finally Marquez spoke up.

âWhat's happened to the trees?'

We pulled our horses to a stop. The surrounding trees did not look alive. The leaves were like lace, criss-crossing blackly over tangles of dead branches. I squinted at one,

holding my hand behind a leaf. My skin showed through, a lighter dark, webbed by the leaf's veins. Up close, the trunks looked like rock. As though the forest had been fossilized.

Forest fires were nothing new on Joya. Da said this small death was needed; that the trees grew back greener, stronger, gave more fruit. Even the scrubland that backed Gromera occasionally smoked and burnt.

But this?

This was different. The leaves hung on their stalks, skeletal and black, yet still attached. The broken bushes oozed black sap, as if the trees were feeding off darkness instead of water.

A light breeze ran over my exposed neck, a smell hooking into my nostrils. Something sharper than smoke ⦠It reminded me of the scent that had filled Pablo's room after the fireworks.

What was it Lupe had said? Something from Asiaâ¦

âSulphur?' Governor Adori spoke the word quietly, almost to himself, but in the dead air of the night it reached us all.

âBoy, come here.'

I glanced across at Pablo, but he shook his head. Governor Adori was looking straight at me. I nervously nudged the mare towards his horse.

âThat map you have, the old one ⦠Does it suggest this⦠change?'

Without a torch nearby, the inside of the satchel should have been impossible to see, but the wood-light, the piece of

Da's broken walking stick, was shining softly through the thin fabric of my rolled-up dress. As I made to pull out the worn map of the Forgotten Territories, thick fingers closed roughly around my wrist.

Marquez had dismounted, his face illuminated by the glow from the bag. âThat⦠What's that?' Without waiting for an answer, he reached into the satchel. He quickly touched the fragment, as if testing it for heat, then pulled it out, sending maps and instruments falling to the forest floor.

As he held up the glowing wood, its pale light was cast further and the men shrank back. The Governor dismounted, dropping heavily to the ground.

Swinging my leg clumsily over the mare, I half-fell to retrieve the papers and tools before they were trampled by hooves or the Governor's boots.

I crouched down, silently cursing myself for allowing the fragment to be found.

âWell? What is it?' repeated Marquez, as he passed it to Governor Adori. âWhy does it shine like this?'

âI don't know.'

âBut where did it come from?'

âMy father.'

âBefore him?' asked Adori.

âI don't know,' I lied. âIt was passed down to him.'

Without commenting further the Governor slipped the wood-light into his belt beside his keys. I reached out, but Marquez pulled me back by the shoulder, fingers digging

hard into my shoulder. My eyes watered and, blinking rapidly, I dropped my arm.

The Governor looked at me expectantly. I glared back.

âThe map.' Pablo's voice was quiet, but still made me jump. He had dismounted and was holding out a pile of papers.

Mouthing thanks, I riffled through with shaking fingers and found the map scrolled in its sheath of cloth.

âWell?' The Governor was still staring. âThe trees?'

I examined the parchment, then shook my head. It held no clues, the key just showed the forest to be a mix of dragon and pine trees. I wondered how I would show the black trees on my map.

Marquez tutted impatiently. âHow much further does the forest stretch?'

I glanced down again, checking the scale against my leather pad. It was inaccurate, but not by much.

âAt least twenty miles in that direction.' I pointed west. âMore if we go straight.'

âAnd how far to water?'

My fingers brushed the blue star that marked the waterfall. âTwelve.'

The Governor nodded. âTake us there.'

âThe trees are starting to thin,' said Marquez. âWe won't have a path to follow much longer.'

âLupe would look for water,' said the Governor, indicating the dried-up bed of the Arintara.

No

, I thought.

She's not that sensible. She's looking for

the killer

.

âSir,' ventured Marquez, âdon't you think it would be better to stop for the night, and rise at first light? She's unlikely to be far ahead, and surely she would have stopped to rest.'

âIf she has, it's all the more reason to continue, Marquez,' snapped the Governor. âWe could catch up.'

âThe men are tired, sir,' said Marquez cautiously. âIf we encounter danger, we will need our strength.'

âAnd what of my daughter's safety?'

âShe would be better served by rested men and rested horses,' continued Marquez. âWe can start tomorrow at a gallop, we'll find her by sundown.'

I wanted to carry on, but with every blink my eyelids felt heavier.

Finally, the Governor straightened his broad back and spoke to us all.

âWe continue.' His glare cut short the murmurs of the men. âAnd I suggest we pick up the pace.'

I carefully replaced the papers and instruments in the satchel, rolling the map back into its cloth. When I looked up the group had already moved on. Only Pablo was there, holding the reins of my horse.

âReady?'

I nodded, grateful he'd stayed behind. Chancing a smile, I reached out for the reins. Instead he handed me a bundled piece of cloth. My dress.

âIt fell out of your satchel. Put it away. Quickly.'

Pablo threw me across the saddle and pushed the horse forward before I had even sat up.

âThank youâ'

âJust pretend a bit better,' he snapped. âThe only reason no one sees is because they don't care enough to look.'

In first hours of daylight, the landscape was even stranger. Black forests had never been mentioned by Masha or the other elders, nor in Da's stories or on Ma's map. What had happened here, to make the trees' colours fade? It couldn't be the drought that made the plants grow like this. The wheat in Gromera was still gold, not grey.

We rode on for a couple more hours, uninterrupted and quiet except for the horses and the scratch as I marked every hundred paces on the leather pad.

Every line brought us closer to Arintan. Butterflies swooped in my stomach as we neared the waterfall. Pablo and Da might think it was just a story, but Arinta had always given me courage, and I needed that now.

We rounded a thick copse of trees, and my heart sank. No Lupe, and no cascading waterfall. Only the cracked bed of the River Arintara running low and sluggish.

âThis is the mighty Arintan?' said the Governor, voice thick with disdain. The others dismounted but I nudged my horse forward.

Around another bend, a rocky overhang rose above my

head. A weak trickle ran over the edge, and behind it was a cupped space, a cave, which would have been hidden from view were the waterfall as full as in the stories.

My knees jarred as I dismounted. Tethering the reins to a tree, I waded into the river, Gabo's boots sloshing and stirring up mud, and walked into the cave.

The space was deeper than I first thought. The entrance was small and low, but at its darkest point was a wide passage, leading to another cave where I could stand. I stumbled blindly, feeling my way forward.

The walls were dry and oddly warm. I could feel strange horizontal lines on the back wall, as if the rocks had been laid flat together. It made me think of a game Gabo and I had played, singing and layering hands over one another faster and faster, drawing the bottom hand out and trying to be at the top when the song ended.

My breath caught. Missing Gabo always crept up like this. I would not allow it.

Feeling my way back into the open air, I scooped some water into my hands and drank. It was not the magical waterfall of Da's stories, but at least there was water.

I refilled my empty water flask and put it in my satchel, bringing out the full one from home and placing it on to my belt. Da always said it was important to use the staler water first on a journey, however tempting it was to drink the freshest.

The Governor and his men were settling on the riverbanks. I sat next to Pablo on a boulder. âWhat's happening?'

I whispered.

âWe're going to have something to eat. Stopping an hour at the most, he says.'

âAnd then?'

Pablo shrugged. âThen we keep going. I'd sleep if I were you.'

But I suddenly didn't feel tired, even though we had ridden through the night and past sunrise.

The Governor was standing a little apart, scanning the ground. Looking for traces of his daughter. He didn't seem able to stay still, as if his anger was turning into hot coals beneath his feet. Guilt churned sharply in my stomach. His eyes flicked towards me, and I looked quickly away.

âRunts,' called Marquez, snapping his fingers. âFetch some wood.'

I stood up, placing the satchel on the rock. I managed to find only a little kindling, but it didn't matter because Pablo emerged from the forest with an enormous bough of what looked like a dragon tree, black like the rest.

The men laughed, clapping him on the back, but his face remained set in a scowl. A fire was soon heating up a pot of stew made with chickens brought by the cook. I shuddered when I passed the pile of plucked feathers, and as the smell wafted through the air I fed Miss La, grateful she was here, a piece of home, grateful even for her pecks.

As the stew began to bubble, I decided to start on my map. But the satchel was no longer on the boulder. Had one of the men mistaken it for their own? My gaze trailed

to the river.

The satchel was bobbing there. Heart pounding in my ears, I plunged my hands into the water. The satchel sloshed as I opened it, fingers trembling over the buckles. Papers and quills twisted and floated inside, and I upended it like emptying a disappointing catch from a net.

Ink had run from Da's star chart and stained through several sheets of blank paper. It was now a mess of black and red, barely legible. It would be impossible to create an accurate map if I couldn't cross-check the stars' positions. But that was not the worst of it. Ma's map was damp and stuck together. I held my breath and peeled it open. Surprisingly, it opened easily.

But this was not the map I remembered.

The drawings of forests were gone. Instead, the blankness at the centre was full of thick lines, the ones I had seen faintly when I had held it up to the light. They looped and crossed as the silk of a spider's web does, or the channels of a maze. In fact, the more I looked the more I was certain that this was what it was. But some of the lines ran through the area we had just crossed, and there had been no sign of roads there.

Perhaps it was the ancient layout of Joya? No villages were marked and, apart from the lines, the only shapes were circles dotted about the edges. At the centre was another circle, larger than the others, and drawn in red. This was the only colour on the map.