The Girls from Ames (44 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

The Ames girls, 1981 Top row: Karla, Cathy, Sally, Karen Middle row: Jane, Angela, Marilyn, Sheila Bot tom row: Diana, Jenny, Kelly

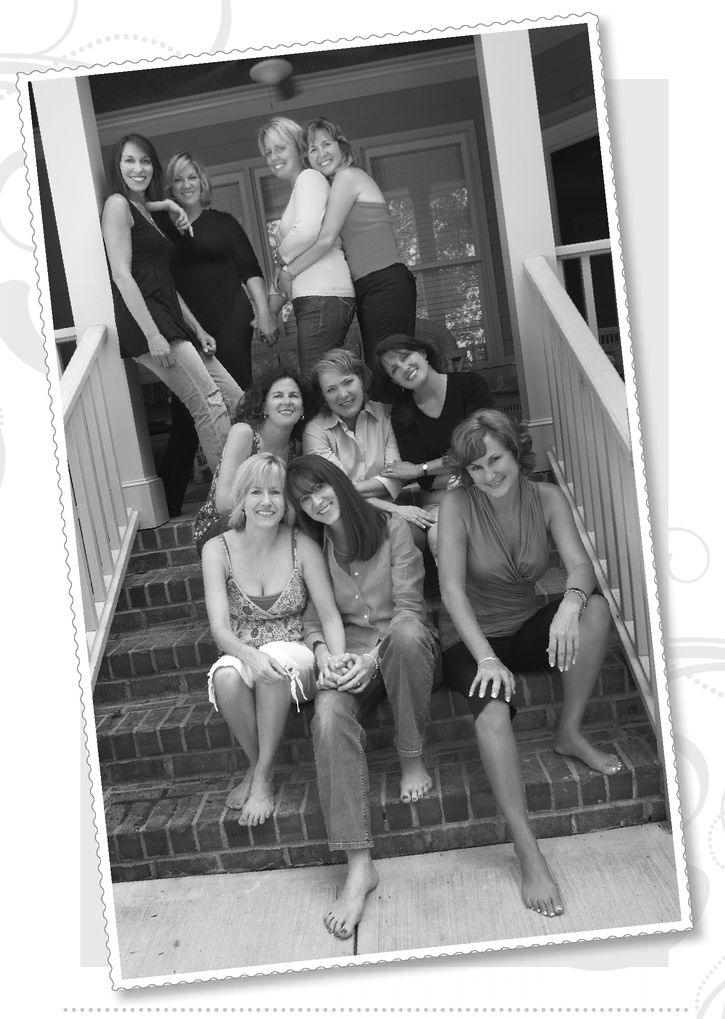

The Ames girls today, in the same pose from the 1981 shot on the previous page

Afterword

T

he week that the hardcover edition of this book was released, in April 2009, the Ames girls were called home.

he week that the hardcover edition of this book was released, in April 2009, the Ames girls were called home.

First, they were invited to sign copies of

The Girls from Ames

at the local Borders store in Ames. They sat at a long table, a ten-woman assembly line, scribbling their names beside their childhood photos at the front of the book. The line of townspeople kept backing up, as the girls spotted familiar faces—old teachers, neighbors, classmates, cousins—and rose to share hugs and memories. They signed a couple hundred books.

The Girls from Ames

at the local Borders store in Ames. They sat at a long table, a ten-woman assembly line, scribbling their names beside their childhood photos at the front of the book. The line of townspeople kept backing up, as the girls spotted familiar faces—old teachers, neighbors, classmates, cousins—and rose to share hugs and memories. They signed a couple hundred books.

After that, the Ames girls drove across town to a meeting room at Iowa State, where they had been asked to make an appearance. As the author, I was invited, too.

None of us knew what to expect. I figured it might be a small crowd. Maybe most everyone who was interested had already stopped by the bookstore to say hello.

But when we arrived, it was a remarkable sight. More than five hundred people had crowded into the room. It felt as if the entire town had come to wish the Ames girls well and to recognize the power of friendship.

The women took the microphone, one by one, and spoke of how Ames remains in their hearts, and about the values they had absorbed there. They talked about their parents and other adults in town who taught and inspired them. They then gave brief updates on their families and the places they now live. Karla, struggling with her emotions, chose not to mention Christie’s death. Many in Ames were aware of Christie’s passing, and the rest all seemed to have the book in their hands. Soon enough, they’d reach chapter twelve and they’d know.

Sheila’s mother and brother had driven up from Kansas City, and were invited to share the stage with the Ames girls. It was an overwhelming and tearful moment for everyone, standing there together, feeling Sheila’s presence. Jenny told the audience that the Sheila Walsh Scholarship at Ames High School had been put into place, funded in part by a portion of proceeds from this book. It would be awarded annually to a female graduate nominated by her peers. “The main qualification is that the winner be a good friend to others, just as Sheila was to us,” Jenny said.

Kelly didn’t say much, but she found herself smiling, soaking it all in. “What an incredible night,” she thought, “being here to witness my friends speaking so articulately. I’m so proud of them.” On stage, Kelly briefly mentioned her bout with breast cancer—there had been no recurrence, she was feeling good—and then Angela talked about her own cancer journey.

Angela explained that she had the same form of inflammatory breast cancer that had killed her mom in 1995 at age fifty-two. In the back of her mind, she always knew cancer was a possibility because of her family history. “But I thought I’d be in my fifties, not forty-six with a nine-year-old daughter.”

She told the crowd that after she began chemotherapy, the other Ames girls rallied to her side with gifts of robes and candles. They ordered a cleaning service for her house, and sent flowers after every treatment. Kelly and Jenny even drove down to North Carolina together. Knowing Angela would be losing her hair due to the chemo, they wanted to be with her for moral support when it was time to shave her head. (It’s best to shave before the hairs start falling out in bunches.)

Kelly had lost her own hair during chemo, and it had grown back. So she thought it would be helpful for Angela’s daughter, Camryn, to see her with a full head of hair. She could be a living, upbeat example that Angela’s hair loss would not be forever, that life could return to normal after cancer treatment. “Kelly and Jenny helped me turn something that could have been traumatic into something that was very ceremonial, and even fun,” Angela said.

She told this story very lightly to the Ames audience. She didn’t talk about the raw emotions everyone was feeling as her head was shaved, or how powerful a moment it was when Jenny and Kelly both leaned forward to kiss her bald head. She didn’t describe how her daughter had stood there, soberly watching this lifelong sisterhood in action. Or that Kelly had broken into tears. “Are you sad because you’re remembering your own treatments?” Angela asked her. Kelly had nodded her head yes. But actually, Kelly’s emotions had swelled for other reasons: She worried that her own fear of dying and leaving behind motherless children would be felt by Angela.

In Ames, Angela skipped these harder memories and spoke with a smile. “So my head was shaved, Kelly and Jenny went home, and they kept calling: ‘So did your hair fall out yet?’ And I kept telling them, ‘No, not yet.’”

Days went by and then weeks. Her hair wasn’t falling out. It was almost comical. Her friends had left town and left her with a shaved head—maybe unnecessarily. “I told them, ‘Well, thanks a lot for shaving my head!’” she said.

The crowd in Ames laughed as Angela spoke. There was something joyous in her delivery, despite the obvious pain at the root of her story. She wore a scarf on her head because, eventually, five weeks after her head was shaved, she did lose her hair.

Angela then told the audience about medical studies mentioned in

The Girls from Ames.

“Research shows that women with advanced stages of breast cancer have better survival rates if they have close friends,” she said. “I believe this. My friends have helped me remain hopeful and optimistic. It’s their love, actions and prayers that will make me a survivor.”

The Girls from Ames.

“Research shows that women with advanced stages of breast cancer have better survival rates if they have close friends,” she said. “I believe this. My friends have helped me remain hopeful and optimistic. It’s their love, actions and prayers that will make me a survivor.”

The crowd applauded and the evening continued. The Ames girls had become hometown celebrities.

A week later, back home in North Carolina, Angela had a mastectomy. She told the Ames girls that she went into surgery feeling buoyed by her visit to Ames, as if she had been physically strengthened by the embrace of her community and by the love of her friends.

The rest of the Ames girls also returned to their private lives. Meanwhile, around the country, women who’d never been to Ames, who might not even be able to place it on a map, began immersing themselves in this book.

I

n the weeks and months after the book’s release, it was a thrill for the Ames girls to hear from so many readers. In email after email, women wrote that reading the book led them to reflect on their own childhood friends. Hundreds of women visited

www.girlsfromames.com

to post heartfelt stories about their longtime bonds, offering vivid reminders of the old saying: “You can make a new friend. You can’t make an old friend.”

n the weeks and months after the book’s release, it was a thrill for the Ames girls to hear from so many readers. In email after email, women wrote that reading the book led them to reflect on their own childhood friends. Hundreds of women visited

www.girlsfromames.com

to post heartfelt stories about their longtime bonds, offering vivid reminders of the old saying: “You can make a new friend. You can’t make an old friend.”

We heard from a group of fifteen women who call themselves “Las Quinceaneras” (The Chosen Fifteen). They met as first-graders in Cuba, lost boyfriends during the Bay of Pigs incident, later escaped to the United States and have maintained their friendships for fifty years.

We heard from four Illinois friends in their forties whose favorite activity over the years has been scrounging up tickets to

The Oprah Winfrey Show

. They’ve gone together twelve times, and have also made girlfriend pilgrimages to see Dr. Phil, Ellen DeGeneres, Tyra Banks, David Letterman, and Regis and Kelly.

The Oprah Winfrey Show

. They’ve gone together twelve times, and have also made girlfriend pilgrimages to see Dr. Phil, Ellen DeGeneres, Tyra Banks, David Letterman, and Regis and Kelly.

All sorts of groups told us they have their own way of referring to themselves: The SSGs (Same Sweet Girls), The Doo Wha Diddies, The Hens, The Magnificent Seven, The Losers, The Maf (as in Mafia), The Council, The Goula Belles, The Sweet Potato Queens, The Green Pinto Gang, The Fearsome Four, The Zig Zaggers. The DGs wouldn’t tell us why they call themselves The DGs. They’ve vowed to take their secret to the grave.

Book clubs all over the country began inviting various Ames girls to call in to their gatherings via speakerphone. I’ve joined the calls, too, and have been so impressed by the penetrating questions and intuitive comments. (Our contact information and a book club guide are on the book’s Web site.)

It also has been great fun to see how these book clubs embrace the spirit of the book. Some have baked and decorated their own brown-blobbed “Shit Sisters” cakes to serve during discussions. Two groups made Maxi Pad slippers and sent us photos. One book club made a CD for each member with all the music mentioned in the book. And a great many groups of women have posed for staircase photos, mirroring the Ames girls’ photo on the book’s front insert. We were even sent a photo of one group of male friends on a staircase.

“I feel as though I take away positive, helpful information from every encounter with a book club,” Kelly told me. “I’ve had some good laughs with all of these women. They’ve helped make me a more enlightened person.” Almost every week, people tell her that they are the “Kelly” in their group of friends. “I’m not exactly sure what that means,” Kelly says, “but it makes me smile and feel less alone in the world.”

Each Ames girl has discovered how readers relate to their “character.” Jane, for instance, as the only Jewish girl in the Ames friendship, hears from women who played that role in their own groups of friends, or were the only Christian in a group of Jewish friends.

Sometimes readers take the Ames girls by surprise. Karen was signing books at a bookstore in Massachusetts, and a woman in line complimented her on her necklace. “Thank you,” Karen said, then looked into the woman’s misting eyes and realized she had read chapter thirteen. As always, Karen was wearing the gold chain with the “mother and child” charm on it, in memory of her daughter lost to spina bifida. The woman showed Karen her own necklace; her charm was also for a child who had died. It was a fleeting encounter, but Karen was taken by the power behind it. They were two strangers, crossing paths briefly, connected by loss.

Some readers became protective of the Ames girls. A woman in Hawaii wrote to take issue with Diana’s description in the book’s “Guide to the Ames Girls” and on our Web site. I’d written that Diana “works at a Starbucks in Arizona.” Given the challenges women face balancing work and motherhood, the reader asked that Diana’s description be changed to: “certified public accountant by profession; now works at Starbucks by choice.” Good point. For this edition, we’ve made the change.

Many readers saw parallels to their own lives when they read chapter six, about the night some of the Ames girls turned on Sally at a sleepover. We heard from readers who recalled being “mean girls” themselves; others shared memories of being targeted. They wanted Sally to know how much they admired her for holding her head high, and for finding it in her heart to forgive. “I’ve forgiven everything,” Sally told a crowd at a bookstore in Minnesota. “I mean, it happened such a long time ago. It happened thirty years, six months, five days, six hours and ten minutes ago—not that I’m keeping track . . .”

It was the perfect laugh line, a reminder of the good humor Sally has brought to the Ames girls in the decades since that incident.

The Ames girls have slowly gotten used to the fact that thousands of strangers now know details of their personal lives and embarrassing moments from their childhoods. But people have been so gracious and supportive that the attention rarely feels intrusive.

A few months after the book came out, Jane and Diana amused the other girls by buying T-shirts with the words: “What happens in the cornfields stays in the cornfields.”

Nice sentiment. But at least for the Ames girls, it’s a directive that came way too late.

S

ince writing the book, I am often asked about the differences between male and female friendships.

ince writing the book, I am often asked about the differences between male and female friendships.

My answer: Because I now hear every day from groups of women, I am constantly being reminded of the incredible power in female friendships. I envy the ease with which women share their lives. I envy the vital ways they support each other emotionally, especially as they get older.

I had mentioned in the book’s introduction that I play poker with the same guys every Thursday night. We almost never talk about our personal lives. We just talk about the cards.

I found myself telling book clubs that my poker buddies didn’t even know my children’s names. But then I wondered if I was exaggerating this. So a few months after the book came out, I finally turned to my left at the poker table and casually asked my friend Lance: “Hey, Lance, could you name my children?”

He shrugged, paused to think, and then smiled sheepishly. “I could

re

name them,” he said.

re

name them,” he said.

Though I’ve heard from some groups of male friends who say their bonds and their conversations are deep and emotional, I’ve also heard from readers saying that my poker buddies and I are typical. A woman named Carol, who lives in Wisconsin, told me that she and her female friends share the most intimate details of their lives. That’s in great contrast to her husband and his friends.

Her husband had recently gone on a week-long fishing trip to Canada with four longtime friends. They were in a remote cabin with no TV. Carol wondered: What did they talk about for a whole week? She knew one of the men was having problems with his job. Another’s daughter was about to get married. A third man had health problems. Carol’s husband said none of those issues ever came up. Carol couldn’t believe it. She told him: “Two female strangers crossing paths in a public restroom would share more personal information in five minutes than you guys talked about in a week!”

Other books

Three Brothers by Peter Ackroyd

Summer School! What Genius Thought That Up? by Henry Winkler

Kindred by Adrianne Lemke

The Unexpected Dom #1: Jennifer's Revenge (BBW BDSM Male Submission) by Boehners, Meghan

Dead Heat by Caroline Carver

Hocus Pocus by Kurt Vonnegut

Pleasured by Candace Camp

Mending Him by Bonnie Dee and Summer Devon

The Earl in My Bed: A Forgotten Princesses Valentine Novella by Sophie Jordan