The God Machine (16 page)

Authors: J. G. Sandom

K

OSTER COULD FEEL

S

AJAN STARING AT HIM.

S

HE KEPT

looking at him in that same penetrating way, with those same unfathomable eyes. He turned and glanced at the stallion instead.

Pi

, he thought. Why was that name so familiar? And he wondered, if he filled up his mind with these nonsensical questions, would they replace the memories that still plagued him? He looked back at Sajan. She was still staring at him.

“You were close to her?” Sajan said.

“You could say that.” Somewhere, deep under his feet, tectonic plates ground against one another, rubbing like the haunches of mares.

After a moment, Sajan asked, “And what do you know about the Gnostics, Mr. Koster?”

“Call me Joseph. Please.”

“According to Nick,” she continued, “they're the authors of both the Gospel of Thomas, which you searched for in France, and this new one, which Franklin refers to in his journal—this Gospel of Judas.”

“When I was in France,” Koster said, “I met a woman named the Countess Irene Chantal de Rochambaud. She was a member of the Grande Loge Féminine, a Masonic Lodge of women with a special affinity for Gnosticism. She told me something about them. It's funny,” he added, “but you kind of remind me of the countess. Just a little bit, anyway. She was old—in her seventies—and she had a slight limp, but she was really quite something.”

“I'm sure.” Sajan started to grin. “You are quite the lothario, aren't you, Mr. Koster?”

“Excuse me?”

“It's not every day I'm told by a man that I remind him of a handicapped crone.”

“That's not what I meant,” Koster began to protest.

“Please, go on, Mr. Koster. The Gnostics. I'm fascinated.”

Koster started to say something. Then it suddenly occurred to him. The countess would have delighted in this impudent woman. They were exactly the same. Two peas in a pod.

“According to the countess, the Gnostics were a religious movement, not a people. They didn't believe in the traditional three-tiered hierarchy of the Church: the bishops, priests and deacons. They didn't support centralized power. Instead, they selected a priest from their group, drawing lots for someone to read the Scriptures, and a bishop to offer the sacrament. And each week it was somebody different. Very democratic. Even women participated. But what really marked them as heretics was their belief that to have

gnosis—

a kind of mystical secret self-knowledge—meant that you didn't require the Church, the organization. The more

gnosis

you had, the closer you were to your own human nature, the closer you were to God. That's why the centralized

Church in Rome felt so threatened. To them, Peter and his fellow Apostles were the only real authority, not some mysterious truth residing within. Eventually, nearly all of the Gnostic gospels were lost or destroyed. Many Gnostics were slaughtered for their beliefs. The communities faded away. The Church was determined to destroy them.”

“What's the root,” said Sajan, “the origin of their philosophy? It sounds almost Eastern to me.”

“According to the countess,” said Koster, “many elements of the Gnostic belief system were Babylonian or Chaldean. Gnostics flourished at a time when the trade routes between the Greco-Roman world and Far East were just opening. There is a line of knowledge, she claimed, that stretches from the Babylonians to the Hebrews and beyond. She called it a system of numbers.”

In ancient Babylon, he explained, astronomy was the province of the

magi

, the priests. They believed that numbers derived from planets and stars were divinely ordained. Because of the seven stars of the Pleiades, for example, the number seven was considered good luck. Just as the number forty, which corresponded to the number of days in the rainy season when the Pleiades disappeared, became a number symbolizing suffering and loss, deprivation.

“You know—like Lent, or the number of days Christ spent in the wilderness,” Koster said. “And when this system combined with the number theories of Pythagoras, it had a lasting impression on western numerology.”

All of the medieval Masons were familiar with these systems, he added. They knew them because of the medieval emphasis on Pythagoras and the Neo-Platonists, and because the Masons had their own particular interest in numbers. In the Middle Ages, Masons were generally

itinerant. They moved about from one project to the next. But bandits were everywhere and so they learned not to travel with currency but to rely instead on fellow Masons for shelter and food. What had started as a way of protecting one's person over time became a means of preserving vital trade secrets. Soon a brotherhood was born. Masons passed their knowledge on only to fellow Masons. And when the Crusaders brought new number lore back from the Levant, the Masons were quick to absorb it, and to pass it along.

“The line of the tradition,” Koster concluded, “spanned from the Magian Brotherhood in Babylon, through the Gnostics and the Manicheans, past the Paulicians and Catharists to the Templars and Freemasons that we still see today. You know Nick is a Mason.”

Sajan looked startled. She threw Koster a smile and replied, “I knew Nick was somehow involved, but I thought it was mostly a social thing. You know. For business and such. A networking tool.”

“He's real cagey about it, but I know he takes it quite seriously. Frankly, I wouldn't be surprised if his own personal interests haven't influenced his quest for this Gospel of Judas. I get the feeling it's not just a business opportunity to him, some publishing coup.”

“But what does all this have to do with Ben Franklin?”

“Over time, the brotherhood of Masons became concerned with the more metaphysical aspects of their trade. They developed rituals and regalia. As more members of the middle class became involved, there came to be a new kind of Mason, a Speculative Mason, instead of the Operative Mason, the Journeyman, who worked with his hands. Eventually, the fraternity began to attract some pretty powerful members. George Washington was a Speculative Mason. So was Ben Franklin.”

“Oh, I see,” Sajan said. “I wondered what he was doing

with a copy of the Gospel of Judas. Still, I… Have you had any luck yet translating it?”

Koster shook his head. “I'm afraid not. It's impenetrable.”

“Perhaps I can help,” she replied. “Here. Follow me.” Without waiting for an answer, Sajan turned and headed outside. Koster fought hard to keep up with her. She had incredible energy. They followed the path toward the house.

“What I don't understand is,” said Koster, “how does the founder of Cimbian, a worldwide concern, have time to play around with this mystery?”

“Nick thought I could help. And I'm semiretired these days. I only go in to the office when I feel like it. When he called… Well, you know Nick. It's hard to say no to him. We go back a long way.”

They entered the house through a side door. As Koster moved through the hallway, he noticed the paintings on the walls shift and alter around him. “Hey, you're not wearing a tie pin,” he said teasingly.

Sajan swiveled about, looking back at him over her shoulder. “I took it off years ago, soon after I first built the house,” she replied. Then she smiled. She seemed somewhat embarrassed. “You know, it's funny. I made my fortune developing technologies, specifically wireless circuitry. But each time I wore that damned pin I felt trapped by my last program selection. One is more than one's previous collection of preferences, so to speak, Mr. Koster.”

“God, I hope so,” he answered fervently, and she laughed.

“But my guests usually get a kick out of it.”

Laughter came so easily to her. “Call me Joseph,” he said again.

“I wanted to show you something. When I heard you were coming,” she said, “I started to do a bit of digging

about Benjamin Franklin. I found a reference in a letter that he wrote to a Mme. Helvétius, a noblewoman Franklin wooed while living in Passy, in France, around 1779. It describes a coded journal he kept which Mme. Helvétius had seen only once, by accident, while Franklin was staying at her country estate. Perhaps it's the same code as the one in the journal Nick gave you.”

They entered the living room. It was spacious and bright, with great windows that looked out on the valley below. An impressive cathedral ceiling rushed up toward the heavens, braced by great wooden crossbeams. There was a pair of comfortable overstuffed sofas, a rocking chair draped with a striped Mexican blanket and a wooden desk by the windows. Koster noticed a printout of a handwritten letter on the surface. Sajan picked it up. “Here's what Franklin says in his letter:

‘Of the journal you glimpsed, and the code it is written in, there is nothing more I can tell you, except what you already know, and then this…’”

She gave Koster the printout.

The passage was followed by a series of symbols, like boxes with dots in them, and capital

Vs

, but facing in every direction. Then it suddenly hit him. “The Masonic cipher,” he said.

“The what?”

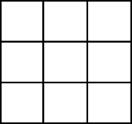

“It uses a pair of tic-tac-toe diagrams and two

X

patterns to represent letters of the alphabet. Got a piece of paper? I'll show you. It was used by Masons back in the Middle Ages to pass messages to each other in secret.”

Sajan opened a drawer and pulled out a pad. Koster placed the letter on the desk and started to notate the sequence. “Letters were enciphered,” he said, “leveraging the shapes of intersecting lines and small dots.” He fleshed out the matrix.

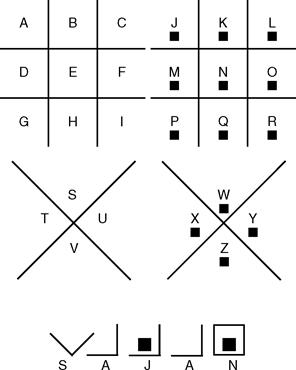

“The name Sajan would be enciphered like this,” he continued.

Sajan pointed down at the letter which Franklin had written to Madame Helvétius. “That's it,” she replied. “It's the same. So what does it say—Franklin's letter?”

Koster scanned the line of figures in the letter. Slowly but surely he decoded the message. Once again, he mapped it out on the pad.

Within the three by three reside the sums of twelve, on any path, to eight from naught

.

“It's nonsense,” said Koster, after he read it aloud. “The three by three? The sums of twelve?”

“What does it mean?”

“I don't know. Three is the number of the Trinity, and therefore of God. And twelve is a compound of the Trinity and four—the four compass points, the four elements—symbols of the material world. According to art historian Émile Mâle, to multiply three by four is to infuse matter with spirit, to proclaim the truths of the faith to the world. It's not an accident that there were twelve Apostles. It was ordained by this number lore. Twelve was also a ubiquitous number in medieval architecture. It's found all over the Notre Dame cathedrals of France.”

“The three by three. Perhaps it's another tic-tac-toe?”

“I don't think so. The code in the journal is different. It's made up of letters, not symbols.”

“Well, what do we know about Franklin? I mean, besides being a Founding Father and everything.”

“Ran away from Boston and his tyrannical brother, to whom he was apprenticed, at seventeen. Came to Philadelphia. Started a successful printing and publishing business. Launched the first public library and fire brigade. Worked with the Assembly against the Penn family. Discovered electricity. Was the only man to sign all four founding papers: the Declaration, the Treaty with France, the Accord with Great Britain and the Constitution—”

“No, no. I mean, what did he do for fun?”

“For fun?”

“Yeah, for fun.”

“He was quite a swimmer when he was younger. A real athlete. Most people think of him as just being bald and fat, with bifocals—which he also invented, by the way.”

“What about when he was older?”

“For fun? I don't know. He liked to play cards. He liked his scientific experiments. He was certainly fond of the ladies, and they of him, even when he was married. But most of the time, he was working. Before moving to Europe as colonial ambassador, Franklin spent hours and hours in the Assembly, listening to the Quakers battle on with the Proprietors and their puppet governors. In fact, he got so bored that he used to make up little games to amuse himself.”

“What kind of games?”

“Mathematical games. Puzzles. You know. He made up these things called magic squares. They were…”

“Were what?”

Koster pounced on the pad. “Three by three,” he repeated. “I forgot all about magic squares. I used to make them up too, when I was a kid.”

“What's a magic square?”

“Look,” he said, starting to map out another diagram on the pad. First he drew two lines going down one way, then two going the other, creating nine boxes in one larger square.