The Good and Evil Serpent (22 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

The head of each serpent is below the hands. An impression of concern, or alertness, is carried forth by the painted, wide-open eyes. The ears are small and more realistic than those of the older woman. As with the former, no feet or legs are visible.

Two exposed full breasts explode outward from a bodice pulled tight, making the breasts rise and protrude. The nipples crown the exposed breasts that are whiter than the rest of the body, and, like the exposed sections of the arms, are clear of any decoration. On the back, the hair flows downward to the upper buttock.

The serpents in the younger woman’s hands are medium sized. They almost reach from her fingertips to her shoulders. These smaller snakes are in contrast to the larger snakes on the older figure.

The young woman seems more naïve and less experienced than the older one. The young woman does not appear as comfortable with the snakes as the older woman. Both women stand erect, with their weight over their feet and breasts thrust forward.

As impressive as these goddesses or priestesses appear, they should be understood within Minoan art. Neither has received the skill and attention of the rhyton (drinking vessel) in the shape of a bull from the Little Palace at Knossos. The goddesses are made of faience and have not been decorated with gold, silver, or gems. The bull libation vase is of steatite. The eyes are made of rock-crystal with red iris. The mouth is white shell. The horns (now restored) are gilded wood.

201

The bull rhyton reveals the Minoans’ inherent love of nature. Yet there is a power generated and felt when one examines the serpent goddesses; surely, it is because of the serpent symbolism.

What could be the symbolic meaning of these serpents held by the full-breasted women? To obtain insights for a perceptive answer to this question we should immerse ourselves in Minoan culture. We must divorce ourselves from the old methodology that provides answers to questions that have not been astutely evaluated; we need to avoid wish-fulfillment conclusions and aim toward those that are well founded.

The palace of Minos in Knossos is almost ultramodern, with running water and a cool lower area. The king and queen’s chambers are sumptuously decorated. The Minoans seem to have lived peacefully together in a common society; something like a corporate personality developed. The setting is ideal. It is most restful in Knossos, when one is sitting by the high palace and looking at the surrounding hills that seem to hug and nourish this spot.

202

The Minoans loved nature; they focused their art on depicting marvel-ously beautiful animals and attractively verdant gardens. An elegant fruit stand with molded flowers was found on Phaistos;

203

it dates from the Proto-palatial Period. Focusing only on art and flower appreciation can be misleading, and such blind methodology would lead one to assume that the plantation owners in Mississippi, with their paintings of flowers and flower-decorated cups, lived in a peaceful democratic society in which all were flower lovers.

204

Yet Cretan archaeology does support the conclusion that the Minoans were nature lovers. As R. Castleden states: “Mi-noan art … focuses on themes from nature—crocuses, sailing nautiluses, dolphins, octopuses, swallows, ibexes among them—rather than themes from contemporary events.”

205

Due to the evidence of trade with other countries, the Minoans were influenced by Egyptian and Anatolian art, but they developed their own art in dynamic and creative ways. Hence, the ancient Minoans were not only the first artists within European society. They remain among the most surprisingly skilled in art and iconography.

Life in Bronze Age Crete was robust, dynamic, and prosperous. The youth were well fed and muscular; they enjoyed the challenging sport of bull jumping as is stunningly revealed in the “Bull-leaping” fresco in the Palace of Knossos.

206

During the history of Christianity, the human body was not always admired and often perceived as the source of sex, which was deemed sinful. The Minoans, however, like the Israelites, had a healthy attitude toward the body. The serpent goddesses and other bare-breasted women like the one depicted in terra-cotta and found in the shrine at Hagia Triada (its Minoan name is still unknown) are impressively well made.

207

Not only the goddesses or priestesses, but the average women, if we can depend on the art left for us to study, were often bare breasted.

208

They were “elegant, graceful, poised, well-mannered and sexually alluring, with their breasts displayed and their lips and eyes accentuated by make-up.”

209

S. Alexiou concludes that the snake goddesses are attired in the “dress fashionable in the Minoan court round 1600 BC: a skirt with flounces, an apron and an open bodice leaving the breasts bare.”

210

On Crete, and within Minoan society, the feminine was not feared or marginalized; the female dominated in the most attractive ways.

211

During the New Temple Period, women most likely became dominant, especially in religious ceremonies.

Is the date of the serpent goddesses significant? Yes, archaeologists have uncovered a vast amount of evidence that the Old Temple Period or Proto-palatial Period (2000–1700) ended abruptly and with a cataclysm that destroyed Monastiraki, Phaistos, and Knossos. Archaeologists found not only evidence of fire, but also leveled buildings and crushed pottery mingled with lime, especially at Phaistos.

212

One event need not be sought to explain the widespread destruction, and the catastrophic fires may not have happened on the same day, yet it is evident that an earthquake caused some of the destruction.

213

Earthquakes also devastated Crete in 1450

BCE

, 1650

CE

, and 1956

CE

.

214

An “earthquake storm” seems to have struck the entire eastern Mediterranean world from about 1225 to 1175

BCE

.

215

It is certain that earthquakes have shaped human history; Khirbet Qumran shows signs of the earthquake in 31

BCE

, and at Sussita the columns of a church lie in parallel lines due to the earthquake of 749

CE

.

The snake goddesses were made shortly after the earthquake in 1700

BCE

, the event that probably brought to an end the first Palatial Period.

216

Their meaning may well be connected with this horrible event and the attempt by the Minoans to comprehend it.

One can imagine the Minoans bemoaning their fate and calling on the gods for assistance. What gods would be implored? Surely, the Minoans would appeal to the gods who controlled the ground, the ones who were causing the earth to move. What chthonic symbol would be most appropriate?

The answer is the serpent, the animal that was seen habitually burrowing into the earth.

217

These observations and insights are corroborated by the recognition that Potnia, most likely the name given to the mother serpent goddess, is the Earth Mother.

218

A tablet recovered from the archives at Knossos mentions an offering offered to “da-pu-ri-to-jo po-ti-ni-ja” which means “Potnia of the Labyrinth.”

219

Since the offering is honey and since it is offered to Potnia, it seems evident that the goddess was represented by a living serpent housed beneath the surface in one of the subterranean labyrinths at Knossos.

One is reminded of a legend about Homer, who dug a trench in the earth and offered libations of milk, honey, sweet wine, and water for the dead. While it is not certain that Homer was thinking about serpent symbolism, his actions take us back to a time when such liquids were offered to snakes. Their chthonic nature becomes apparent.

Snakes were revered on ancient Crete. Their relation with honey is also grounded. Archaeologists recovered a terra-cotta snake that is crawling above a honeycomb. The figure also dates from the New Palace Period.

220

Vases for use in the worship of domestic snakes are on view in the Hera-kleion Archaeological Museum.

The dove was associated with goddesses on Crete. Most likely the dove signified fertility, procreation, and perhaps love.

221

We know that the Minoans traded with nations in the east, including Palestine. We also know that their art was influential on the Canaanites. Were the cult stands at Beth Shan, with the clay serpents and doves, influenced by Minoan iconography and symbolism? That discovery would not be surprising.

The exposed breasts of the women could also be a key to the meaning of the ophidian symbology of the goddesses—fertility, power, beauty, motherhood, and the desirable all come to mind. If the creator of these masterpieces, who represented the naturalism of the new period that began after 1700

BCE

,

222

did not have all these ideas and concepts in mind, surely many of those who viewed them in ancient Knossos would have these, and similar ideas, brought to consciousness. Other realia show that the Minoans depicted women, priestesses probably, dancing. Perhaps one is reminded of the poetry of the tenth Muse, the poetess Sappho of about 600

BCE

. Recall Sappho’s words:

And their feet move

rhythmically, as tender

feet of Cretan girls

danced once around an

altar of love, crushing

a circle in the soft

smooth flowering grass.

223

A gold ring, dating about one hundred years after the faience snake goddesses, was found near Knossos, in the tomb of Isopata; it is elegant and shows “a religious scene which may represent an ecstatic ritual dance and an ‘epiphany’ of a goddess.”

224

The snake also appears on a gold amulet.

225

The artworks on Crete, in contrast to those on the southern plantations, were not merely decorative; they served the spiritual dimensions of Minoan culture. The women, after all, are goddesses. Their long triangular skirts, like the Egyptian pyramids, anchor them with the earth and draw one’s eyes eventually downward. The older woman points downward with the serpents on her arms. From the waist of both goddesses hangs a garment that directs one’s attention to the earth. Surely, we should finally conclude that among the many meanings of the serpent represented by these faience objects is the worship and adoration of the serpent, the god of the world beneath the earth. When one is reminded that in ancient cosmology that is also the place of the “underworld,” then one can connect with these images the concept of the serpent as the one who knows the secret of immortality.

Finally, let me reflect on the type of serpents held by the goddesses. Three types of snakes are native to Crete: the Balkan Whip Snake

(Coluber ge-monensis)

, the Leopard Snake

(Elaphe situla)

, and the Dice Snake

(Na-trixz tessellate)

. None is poisonous. The goddesses do not hold poisonous snakes, since neither ancient fossils nor modern species on Crete are poisonous.

226

The markings of the snakes are not realistic; judging by length, the older woman may be holding Dice Snakes or Leopard Snakes and the younger one two Balkan Whip Snakes.

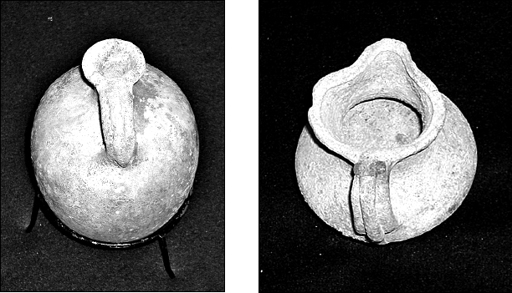

Figure 29

.

Left

. Canaanite Bowl with Serpent on Handle. From Jerusalem or the environs of Jericho. JHC Collection

Figure 30

.

Right

. Canaanite Serpent Pitcher. From Jerusalem or the environs of Jericho. JHC Collection

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE OF MINOAN INFLUENCE AMONG THE ANCIENT CANAANITES: THE SERPENT BOWLS FROM ANCIENT PALESTINE

Four new discoveries must suffice to conclude our study of serpent iconography among the Canaanites in ancient Palestine, which, as we have indicated, was significantly influenced by Minoan art and culture. These objects were not previously known.

The ceramic vessel in

Fig. 29

is 14.1 centimeters high and 8.9 centimeters wide.

227

It is most likely an example of Canaanite art of the Middle Bronze Age. It is rounded on the bottom and may have been intended to stand upright in sand. The aspect of interest for us is the appliquéd clay on the handle. In light of our previous research and the following study, it is evident that a serpent is intended in a stylized shape. There is no tail, no head. In light of the insights already obtained, it is apparent that a serpent was placed on the vessel, perhaps to protect the contents and not merely to provide decoration. It is conceivable that in a snake cult the serpent would be offered water or milk that could be inside the vessel.