The Good Soldiers (7 page)

Authors: David Finkel

Tags: #History, #Military, #Iraq War (2003-2011)

“Shukran,”

he said, taking the man’s hand.

“I’m sorry I cannot support you,” the man said. “I’m afraid for my life.”

He escorted Kauzlarich outside, and as Kauzlarich and his soldiers moved on, the man was immediately surrounded by neighbors.

“He wasn’t nervous about us. He was nervous about the people outside wondering what he was telling us while we were in his home,” Kauzlarich would say later. “It’s a catch-22. They want security. They know we can provide it. They need to tell us where the bad guy is, but they fear for their life, that if we don’t do anything about it the bad man will come and kill them. They’re damned if they do, damned if they don’t.”

Where was the bad guy, though? Other than everywhere? Where was the specific one who had set off the IED? Back at the fresh hole now, surrounded by neighborhood children who were shouting, “Mister, mister,” and clamoring for soccer balls, Kauzlarich wondered what to do next. Surely someone in the neighborhood knew who had done this, but how could he persuade them that as damned as they thought they would be for dealing with the Americans, they would be more damned if they did not?

Strength was part of counterinsurgency, too. He decided to call in a show of force, which would involve a pair of F-18 jets coming in over the neighborhood, low and without warning. The sound would be ear-splitting and frightening. Houses would vibrate. Walls would shake. Furniture would rattle. Teacups might topple, though Kauzlarich hoped that wouldn’t be the case.

He and his soldiers got in the Humvees to leave, and now another thing happened that hadn’t happened before—the children applauded and waved goodbye.

Off the soldiers went, feet aligned, hands tucked, eyes sweeping, jammers jamming, creeping back to the FOB.

Here came the jets.

3

MAY 7, 2007

Our troops are now carrying out a new strategy in Iraq under the leadership of

a new commander, General David Petraeus. He’s an expert in counterinsurgency warfare.

The goal of the new strategy he is implementing is

to

help the Iraqis secure their capital

so they can make progress toward reconciliation and build a free nation that respects

the rights of its people, upholds the rule of law, and fights extremists alongside the

United States in the war on terror. This strategy is still in its early stages . . .

—

GEORGE W. BUSH

,

May 5, 2007

O

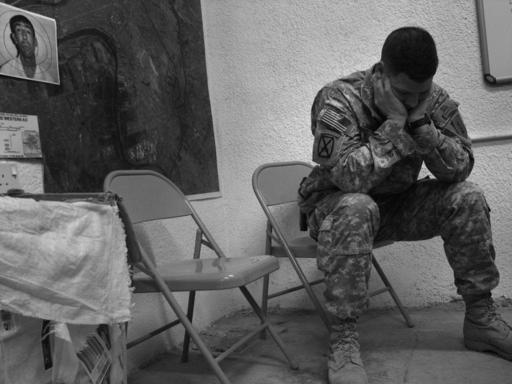

f all the soldiers in the battalion, none was closer to Kauzlarich than Brent Cummings. Three years younger than Kauzlarich, Cummings had joined the army for the admittedly simple reason that he loved the United States and wanted to defend his admittedly sentimental version of it, which was his family, his front porch, a copy of the Sunday

New York Times,

a microbrewed beer, and a dog. He had been with the battalion since its very first days, and believed, so far, in the 2-16’s mission as morally correct. As Kauzlarich’s number two, Cummings tried to approach the war with the same level of certainty. But he was more brooding than Kauzlarich, and more introspective than most any soldier in the battalion, which resulted in a deeper need from the war than merely a desire for victory. As he said one day when describing differences between Kauzlarich and himself: “He can see despair, and it doesn’t bother him as much as it bothers me.”

That ability to be bothered, and the need to ease it by at least trying to act with decency, was why Cummings was on his telephone one day getting increasingly upset.

Brent Cummings

“We have to remove the human waste

and

the body. And that’s going to cost

money”

he was saying.

He paused to listen.

“Yeah, they’ll say, ‘Buy the bleach,’ but how much bleach do I have to buy?They’ll say, ‘Buy the lye,’ but, Christ, how much will

that

cost?”

He paused again.

“It’s

not

water. It’s

sewage.

It’s

yeccchh.”

He took a breath, trying to calm down.

“No. I haven’t seen Bob. Only pictures. But it looks awful.”

Sighing, he hung up and picked up one of the pictures. It was an aerial view of Kamaliyah, the most out-of-control area in the AO. Sixty thousand people were said to live there, and they had been largely ignored since the war began. Insurgents were thought to be everywhere. Open trenches of raw sewage lined the streets, and most of the factories on the eastern edge had been abandoned, one of which had a courtyard with a hole in it. That was where soldiers had discovered a cadaver they began calling Bob.

Bob

was shorthand for bobbing in the float, Cummings explained.

Float

was also shorthand, for several feet of raw sewage.

And what was “bobbing in the float” shorthand for? He shook his head. He was exasperated beyond words. The war was costing the United States $300 million a day, and because of rules governing how it could be spent, he couldn’t get enough money to get rid of a cadaver that was obstructing the 2-16’s most crucial mission so far, bringing Kamaliyah under control. It needed to be done quickly. Rockets and mortars were being launched from Kamaliyah into the FOB and the Green Zone, and intelligence reports suggested that EFPs and IEDs were being assembled there as well.

The factory, which once produced spaghetti, of all things, was the key to how this was going to be done. An essential part of the surge’s counter-insurgency strategy involved moving soldiers off of FOBs and into smaller, less imposing command outposts, or COPs, that would be set up in the middle of neighborhoods. The thinking behind COPs was best summed up by David Kilcullen, a counterinsurgency expert who was an adviser to General David Petraeus and who wrote in a 2006 paper widely circulated in the military: “The first rule of deployment in counterinsurgency is to be there . . . If you are not present when an incident happens, there is usually little you can do about it. So your first order of business is to establish presence . . . This demands a residential approach—living in your sector, in close proximity to the population, rather than raiding into the area from remote, secure bases. Movement on foot, sleeping in local villages, night-patrolling: all these seem more dangerous than they are. They establish links with the locals, who see you as real people they can trust and do business with, not as aliens who descend from an armored box.”

So important were COPs to the surge that Petraeus’s staff tracked how many there were as one of the indicators of the surge’s effectiveness. Every time one was established, battalion would send word of it to brigade, which would send word to division, which would send word to corps, which would send word to Petraeus’s staff, which would add it to a tally sheet that was transmitted to Washington. Kauzlarich, so far, had added one to the list—a COP for Alpha Company in the middle of the AO—but wanted to add more. A second COP would soon be installed for Charlie Company, in the southern end of the AO, but, for tactical reasons, the COP needed most of all would be the one for Bravo Company, up north in Kamaliyah. The middle of Kamaliyah was too unstable for one, but the edge seemed safer, and that’s where the abandoned spaghetti factory was.

So in went some soldiers, breaching the gate and swarming inside, where they discovered rocket-propelled grenades, hand grenades, mortar shells, the makings of three EFPs, and a square piece of metal covering a hole that they suspected was booby-trapped. Ever so carefully they lifted the cover and found themselves peering down into the factory’s septic tank at Bob.

The body, floating, was in a billowing, once-white shirt. The toes were gone. The fingers were gone. The head, separated and floating next to the body, had a gunshot hole in the face.

The soldiers quickly lowered the cover.

By now they had dealt with bodies, including a man they’d hired to help build Charlie Company’s COP who had been executed soon after starting work. That death had been especially gruesome; whoever killed him had done so by tightening his head in a vise and leaving him for his wife to discover. But Bob, somehow, seemed even worse. Unless the body were removed, it would be there day and night, afloat in the float during meals and sleep, and how could the 120 soldiers of Bravo Company ever get comfortable with that?

“It’s a morale issue. Who wants to live over a dead body?” Cummings said. “And part of it is a moral issue, too. I mean, he was somebody’s son, and maybe husband, and for dignity’s sake, well, it cheapens us to leave him there. I mean, even calling him Bob is disrespectful. I don’t know . . .”

The need for decency: suddenly it was important to Cummings in this country of cadavers to do the proper thing about one of them. But how? No one wanted to descend into the sewage and touch a dead body. Not the soldiers. Not the Iraqis. And not him, either. So Bob floated on as more days passed and soldiers continued to clear other parts of the factory, every so often lifting the cover. One day the skull had sunk from view. Another day it was back. Another day the thought occurred that there might be more bodies in the septic tank, that Bob might simply be the one on top.

Down went the cover.

Finally, Cummings decided to have a look for himself.

The drive from the FOB to the factory was only five miles or so, but that didn’t mean it was easy. A combat plan had to be drawn up, just in case of an ambush. A convoy of five Humvees, two dozen soldiers, and an interpreter had to be assembled. On went body armor, earplugs, and eye protection, and off the convoy went, past new trash piles that might be hiding bombs, along a dirt road under which might be buried bombs, and now past an unseen bomb that detonated.

It happened just after the last Humvee had passed by. There were no injuries, just some noise and rising smoke, and so the convoy kept pushing ahead. Now it passed a dead water buffalo, on its back, exceedingly swollen, one more thing in this part of Baghdad on the verge of exploding, and now it came to a stop by a yellowish building topped by a torn tin roof that was banging around in the wind.

“The spaghetti factory,” Cummings said, and soon he and Captain Jeff Jager, the commander of Bravo Company, were staring down into the septic tank.

“Well, what I think we do is . . . man,” Cummings said, with absolutely no idea what to do now that he was seeing Bob up close.

“I think you gotta clean it out,” Jager said. “I think you gotta suck all the shit out of there and you gotta clean it out. I think the first step is sucking the shit out, second step is finding somebody to go down there to get it up. It’ll cost some money.”

“Yeah,” Cummings said, knowing the rules about spending money, none of which covered the removal of a dead Iraqi from a septic tank in an abandoned spaghetti factory.

“I mean, we’re gonna have some heartache moving into a building that’s got a dead body in a sewage septic tank,” Jager said. He picked up a long metal pipe and stirred the float until the skull disappeared.

“I mean, someone has disgraced him as bad as you can possibly disgrace a human being,” Cummings said as the skull reappeared. “And there’s a not a playbook that we can go to that says when you open it up: ‘Here’s how you remove a body from a septic tank.’”

Jager gave it another stir. “The one contractor I brought up here, he was willing to do everything here, but he wanted nothing to do with that,” he said. “I asked him how much it would take for him to get that out of there, and he said, ‘You couldn’t pay me enough.’”

“If it were a U.S. soldier, sure. We would be there in a heartbeat,” Cummings said.

“We could drop down there and get it out ourselves,” Jager said. “But—”

“But what soldier am I going to ask to go in there to do that?” Cummings said, and after Jager put the cover back in place, the two of them went on a tour of the rest of the factory.

It was such a mess, with cracked walls and piles of ruined equipment, that it was hard to see 120 soldiers moving in. But Jager assured Cummings it could be done and had to be done. “We know the militia has used this as a base of operations,” he said. “There are reports that they used this for torture and murder.” Bob was evidence of that, he said, “and the guys next door will tell you about screams and the sounds of people being beaten.”

They stepped out of the front gate, onto the street, and more soldiers joined them as they began walking the perimeter. There was already a solid cement wall surrounding the factory, but for security reasons the height would have to be doubled with blast walls, and the streets would have to be blocked off with coils of razor wire.

Around the first corner now, Cummings noticed a mud-brick hovel that had been built near the factory wall, so close that it would have to be swallowed up inside the blast walls. Then he saw clothing hanging in the yard and realized that someone lived there, so he made his way through a gate that led into the property and walked toward a man who, when he saw the soldiers, began noticeably shaking in fear.