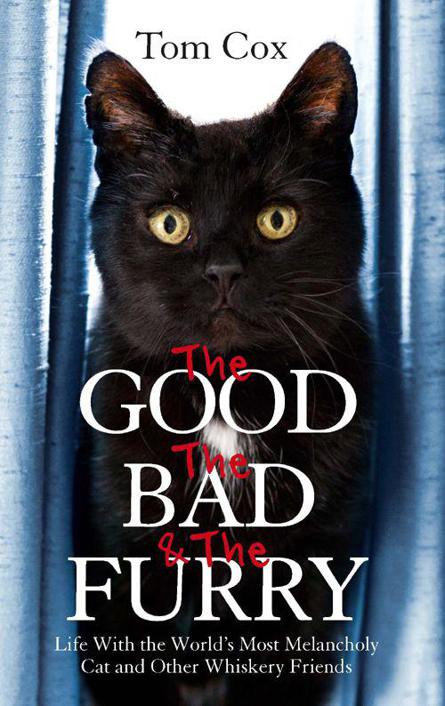

The Good, The Bad and The Furry: Life with the World's Most Melancholy Cat and Other Whiskery Friends

Authors: Tom Cox

Tom Cox is the author of several bestselling books, including two previous memoirs about his adventures in cat ownership:

Under the Paw

and

Talk to the Tail

. He is on Twitter at

@cox_tom

and blogs at

www.littlecatdiaries.blogspot.co.uk

Under the Paw

Talk to the Tail

Published by Sphere

ISBN: 978-0-7515-5239-3

Copyright © Tom Cox 2013

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Sphere

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

For Jo and Mick

Five Highly Unlikely Pet Memoirs

Some Anonymous Cats I Have Psychoanalysed on my Travels (2010–2012)

Keeping our Cats out of the Bedroom: Instructions for Housesitters

It’s Ralph’s World – The Rest of Us Just Live in It

Ten Reasons Why My Oldest Cat Is Sad

‘He absorbed that something in the demeanours of Bears reminds us of ourselves. They have the faces of outcasts.’

Rose Tremain,

Merivel

CATPACITY

For a human to reach the absolute limit of cats a person can reasonably own without doing serious damage to his or her own mental state, or that of the cats. E.g.: ‘Man, I would love to take that kitten off your hands, believe me, but I’m totally at catpacity right now.’

CATPAWCITY

The exact opposite of being at catpacity: a state of catlessness, leading to an unenriched life. Not to be confused with the nineteenth-century American frontier town, Cat Paw City, North Dakota (population 301).

My cat Janet had been

sick outside my back door. Or, as it might have seemed to you, had you never met Janet before and arrived upon the scene as an innocent: a large tanker of vomit had swerved off the road and into my garden, shedding its entire load in the process, and now my cat Janet was inspecting its contents. I knew better than that. Ever since he’d first bounded clumsily into my life a decade earlier, Janet – who was actually a large man cat – had been a master puker, a veritable titan of regurgitation. It had nothing to do with the fact that he’d been ill for the last couple of years. He’d always been the same. Sometimes, sitting several feet away, I’d spot him apparently beginning to re-enact the moves from the video for the 1997 remix of Run DMC’s ‘It’s Like That’ single; then I’d be able to rush over in time to thrust a used broadsheet newspaper or cardboard box in front of his face and avert disaster. But a person couldn’t reasonably be expected to be on vomit stakeout 24/7. At least on this occasion he’d been considerate enough to puke outdoors.

‘You don’t need

to clean that up,’ said my friend Mary, gesturing towards Janet and his vomit. She and her boyfriend Will had been staying at my house the night before and, like me, had been woken up by another of my cats, Ralph, meowing his own name at 5 a.m. ‘Give it a couple of days and a fox will be along to eat it all.’

‘Really?’ I asked. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Definitely. Foxes always eat my mum’s dog’s vomit. They love it.’

‘It’s true,’ said Will, nod-wincing in a manner that simultaneously managed to convey both his faith in Mary’s opinion and his distaste for the eating of vomit.

‘RAAAAAALPH,’ said Ralph, who, despite our previous speculation to the contrary, evidently hadn’t quite finished his daily morning session of meowing his own name.

I have a lot of friends who love animals, but none are more knowledgeable than Will and Mary. The first time I met them, at a used record fair, they told me they’d spent a considerable part of the previous afternoon watching a wasp eat a bench. This pretty much set the tone for our friendship, which revolves roughly half around enthusing about early 1970s Greek progressive rock and half around looking at photos of owls and hares and saying, ‘Yep. That’s a good one.’ If I’m out in the countryside, I’m fairly unconditional in my mission to befriend any creature with four legs or some kind of fur or feathers on it, but I don’t have any of the facts at my fingertips. Will and Mary are different. If I plan a country walk with them, I need to allow an extra forty-two per cent on top of its usual duration just for the time they spend pointing out rare fungi and birdlife. This is great for me, as I get my usual fresh air and exercise buzz, plus the chance to learn lots of new things – yesterday, for example, on an icy walk through the north-western edge of Thetford Forest, I’d found out what a woodcock was by seeing Mary walk up to a woodcock and say, ‘Look! It’s a fucking woodcock!’

Will and Mary were

representative of what had turned out, to nobody’s greater surprise than my own, to be a good year for me. Eighteen months previously, in the spring of 2009, I’d broken up with my partner of almost nine years. A couple of weeks after that a friend had died very suddenly of an undetected brain tumour and I’d been given the news that my nan – my lone remaining grandparent, who’d always been almost like a second mum to me – had terminal lung cancer. I’d found myself alone, in a house far too big for me where everything seemed to be falling to bits, with four of the six cats my ex, Dee, and I had owned, in a county – Norfolk – where none of my family lived and where, it began to occur to me, I hadn’t tried quite as hard as I might to make new friends.

Dee and I had decided on a one-third to two-thirds split of our six cats. This had been solely based on what would be best for the cats themselves, in terms of environment and stress levels. To put it another way, she had taken with her the two young cats who loved each other, while I’d got the four old grumpy ones, each of whom thought the others were giant buttmunches. There was Ralph, a preening tabby who liked to meow his own name outside my bedroom window at 5 a.m., lived in constant terror of my metal clothes horse, took umbrage at cleanly washed hands, and had a habit of bringing slugs into the house on his back. There was his strong, wiry brother Shipley, who stole soup and was constantly mouthing off at everyone, but generally relaxed once you picked him up and turned him upside down. Then there was Janet, who was clumsy, often accidentally set fire to his tail by walking too close to lighted candles, liked bringing old crisp packets into the house, and suffered from a weak heart and an overactive thyroid gland, dictating that I had to find stealthy ways to make him swallow two small pink pills every day to keep him alive.

Finally, there

was The Bear. Now well past his fifteenth birthday, he was a troubled gothic poet of a cat with a penchant for pissing on the bedroom curtains and a meow redolent of the ghost of an eighteenth-century animal – I tended to change my mind as to precisely which

kind

of eighteenth-century animal. Like Janet, The Bear had been Dee’s cat from a previous relationship. More than that, he had the stigma of being her previous ex’s favourite cat. Despite this, we had both agreed that, between Dee and me, he liked me most. There were various undeniable signs of this: for example, he enjoyed getting on my lap and looking deep into my eyes whilst purring, and he had never snuck into a basket of clean laundry and neatly deposited a turd inside the pocket of my dressing gown, or pissed on one of my legs during one of our arguments.

All of these cats

had led me, in the months immediately following our split, inexorably back into a long-defunct relationship. Their stories were mine and Dee’s; their numerous nicknames would, I worried, sound wrong if I said them in the house the two of us had shared, in the presence of someone who wasn’t her. They were the four closest, most painful points on a personal map of Norfolk called ‘Us’ which, whether I liked it or not, had come to define my first, somewhat lost, summer as a single person.

But then something unexpected had happened: I’d begun to feel quite good. Better, and more free, and more

me

, than I’d felt for years. Instead of scurrying away to see old friends who lived in other parts of the country, as I had been doing previously, I began making an effort to meet people close by, and found it amazingly easy. I got to know and fall in love with Norfolk like never before. I ate an apple every day, abandoned the vitamin tablets I used to take, and went on at least one long country walk every week. Before I knew it, I’d gone the first year of my adult life without getting a cold. I was fitter and slimmer at thirty-five than I’d been since I was twenty. If I had any worries that all this had turned me into a big girly post-divorce spiritual empowerment living-in-themoment cliché, the simple fact of my increased happiness suffocated them.

My life now, a year and a half on from the break-up, was one mostly comprised of good friends, dancing, abuse from my cats, hamfisted attempts at DIY, diminishing amounts of TV, and lots of fresh air. I definitely didn’t view my cats as children, but my relationship with my house had become like that of a single parent and a giant, adored problem child with decaying limbs and windows for a face. It was the first building of my own I’d ever loved – a somewhat brutal early sixties structure known as the Upside Down House, whose kitchen was found on the top one of its three floors – but a new bit of it seemed to break every week. The days when I could afford to buy nice new furniture for it or keep it looking tiptop seemed long, long in the past, but I found that I didn’t miss them – wondered, even, if any of that had really been so important to me. My cats were happy and safe, while I had a warm, dry place to sleep and a quiet place to work and read; these seemed like the most important things.

I was also still

high on the amazing, dizzying sense of possibility that came with waking up each day as a single person. But I was aware that that was a novelty with a limited lifespan, and that, as much happiness as I had, it was the kind that came with its own empty compartment. Until last year, I’d been in long-term relationships pretty much all my adult life and it still seemed, to me, like a natural state for a person to be in. I would, despite everything, very much like to be in one again. At least, that’s what I kept telling myself.

‘So,’ said Mary. ‘You haven’t told us how it went last week.’

‘It was

OK,’ I said. ‘No, good. Really nice.’

‘So are you going to see her again?’

‘Maybe. But probably just as friends.’

‘Dude,’ said Will. ‘You are one of the pickiest guys I know.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘I’m a nightmare.’

‘RAAAAALPH,’ said Ralph.

Over the course of the last fourteen months, I’d found no shortage of people wanting to set me up on dates, but little had come of any of those that I’d been on. The problem, more often than not, was my own state of mind. Beth, who I’d caught the train down to London to see the previous Friday, was a case in point. A funny, bookish, curvaceous, dark-haired animal lover who liked 1970s classic rock, she was about as right for me on paper as anyone could possibly be. A couple of weeks earlier, we’d spent a perfectly lovely afternoon by the river in Norwich, followed by a gig at the Arts Centre. ‘There’s something I have to warn you about, if you’re going to date me,’ she had told me during the second half of the evening.