The Grand Ole Opry (2 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

Country music venerates tradition, and the Grand Ole Opry embodies it. There is nothing remotely comparable elsewhere in music.

No show covers all the bases, from street-corner blues to hip-hop or from rockabilly to heavy metal, but every night at the

Grand Ole Opry four thousand people of all ages can hear the broad sweep of country music from the back porch to the stadium.

No one performs more than a few songs per segment, so the show isn’t trapped in one time period. It’s breathlessly varied

and fast-paced, faster and more varied by far than the very first show when Uncle Jimmy Thompson played the fiddle for one

hour to the sole accompaniment of his niece.

Brad Paisley, one of the current stars who has made a sustained commitment to the Opry, has a vision for the show. “Ideally,”

he said recently, “people will come hear Porter Wagoner or Bill Anderson on a night I’m singing and walk away saying, ‘I like

that new guy, too.’ And maybe there’ll be people who come to the show because they’ve heard my songs on the radio and they’ll

say, ‘Boy, I didn’t know Bill Anderson wrote “City Lights,” or I didn’t know Jimmy Dickens’s “Bird of Paradise” is so funny.

I need to go get their CDs.’”

The Opry came into a world with few entertainment options; now, of course, there are so many. Every era had its unique set

of problems, though. In its earliest days, the Opry’s managers had to contend with Nashville’s old-money crowd, who believed

that the show brought disgrace to their community. Today, as the interstates approach Nashville, the offi-cial road signs

say “Metropolitan Nashville, Home of the Grand Ole Opry.” The Opry has made Nashville synonymous with country music, and the

country music business no longer has to trumpet how much it contributes to the city and its economy because the evidence is

everywhere. Those entrusted with the future of the Grand Ole Opry contend with different problems, but the show will survive

because too many people want it to survive. True, there are complaints that it isn’t what it used to be, but it never was.

If it was what it used to be, it would have been fin-ished by 1930.

So much has happened in eighty years, and here for the first time the story is told in the words of those who witnessed it.

Some were in front of the microphone, some behind the curtains, and some in the back office. Some observed and some participated.

Everyone was there. Occasionally memories conflict, but that’s as it should be. No two people have ever remembered the same

event the same way.

For help in preparing this book, I’m deeply indebted to Brenda Colla-day, curator of the Grand Ole Opry Museum and the vast

archive that the Opry has accumulated along the way. The photo selection here is the tip of the iceberg. Brenda also compiled

the list of Opry members by decade and assisted in many other ways. Thanks also to Melissa Fraley Agguini, vice president

of Brand Development at the Opry’s parent company, Gay-lord Entertainment; to Gina Keltner, who helped arrange the interviews;

and to Alex Smithline, whose idea this initially was. Finally, thanks to Steve Buchanan, president of the Grand Ole Opry Group,

and Pete Fisher, manager of the Grand Ole Opry, who are steering the Opry into the twenty-first century with a vision that

would appeal to those who originally conceived the show.

COLIN ESCOTT

Nashville, February 2006

THE AIR CASTLE OF THE SOUTH

O

ne hundred years ago, country music as we know it today didn’t exit.Depending on wher you were, you’d hear Gaelic fiddle tunes,old

English pending on where you were, you’d hear Gaelic fiddle tunes, old English ballads, new American ballads, bawdy cowboy

songs, hymns, or minstrel songs. Undocumented and ignored, it was called folk music because it was the music that the people

of America sang and played for themselves. You’d hear it at weekend hoedowns and barn dances, when families who would rarely

see another family all week would come together to share a meal and play music. The barn dance would be in someone’s barn

with hay bales for seating; the hoedown might be outside or in a church hall or in someone’s front parlor. It would probably

be on bath night, and the women would have curled their hair with curling tongs heated over the flame of the coal oil lamp.

As the nineteenth century ended, few could have foreseen the impact that two recent inventions, radio and records, would have

upon the music played at rural get-togethers. When commercial radio became popular in the 1920s, local music suddenly wasn’t

local anymore. All the pieces of American folk music came together to make country music, and if there was one stage where

it happened, it was the Grand Ole Opry.

Edwin Craig: “I just wanted everybody in this community to have access to this new medium.”

The Grand Ole Opry was one of the first

radio

barn dances. An old idea in a new era, the radio barn dance was a Saturday night hoedown staged in such a way that folks

listening at home could share the fun and excitement. A night at the Grand Ole Opry has almost always included dancers, older

stars, new stars, traditional groups, and comedians. That’s the way it has been for eighty years. Performers came together

on the Opry stage from very different places and very different backgrounds to create a new American art form, country music,

from traditional folk music. The Opry has not only come to define country music but personify the values of the millions who

listen to it.

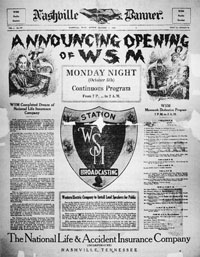

Nashville Banner,

October 4, 1925: “WSM can proudly boast that it is stronger than eighty-five percent of all broadcasting stations in the United

States. The National Life & Accident’s field force of more than 2,500 working in as many cities and towns in twenty-one states

are elated over the great station, and they are telling thousands daily of the station that is destined to put Nashville on

the international radio map.”

Country music was first performed on radio in 1922; the first country music recordings were made in 1923; and the Grand Ole

Opry was launched in 1925. The Opry began as just another show on Nashville’s WSM radio, but the station’s owners, National

Life and Accident Insurance Company, soon realized that it would help them reach a largely untapped rural audience. When National

Life Vice President Edwin Craig launched WSM, it wasn’t Nashville’s first radio station, but, unlike the earliest stations,

it had solid financial backing and the steadfast commitment of its owners.

left: The National Life Building. WSM was on the fifth floor and called itself the “Air Castle of the South.”

right: Engineer Jack DeWitt (second from left) with a group of Scouts. DeWitt was later awarded seven patents.

Once Edwin Craig had secured the funding to start WSM, he bought state-of-the-art equipment. His love of radio and belief

in its potential had already led him to engineering genius John H. “Jack” DeWitt, who would become a key part of Opry history.

PETE MONTGOMERY,

WSM engineer:

Even before WSM went on the air, Jack DeWitt and I experimented with radio in Nashville. We built a transmitter for Ward Belmont

College, and they gave it to us when the dean decided that it used too much electricity. Then we set up in the parlor of the

DeWitt home, and anybody could come and broadcast, but DeWitt’s mother decided she didn’t like all those strangers traipsing

through her house. We moved to First Baptist Church, where they gave us studio space in exchange for broadcasting the Sunday

sermon. We joined WSM when National Life bought a commercial transmitter. I met Edwin Craig, liked him, and decided to work

for him.

JACK D

E

WITT, WSM engineer:

Edwin Craig was the son of one of the founders of National Life, Cornelius Craig, and got interested in radio just by listening

to it. He had a good receiver and he loved to listen to distant radio stations. He wanted to leave the company and start a

radio station. His father said, “You may not leave the company, but if you wish to put in a radio station, do it here.” So

he went ahead, and got the license for WSM, which was National Life’s slogan, “We Shield Millions.” Those call letters had

already been assigned to a ship [the S.S. Fair Oaks], but Edwin Craig wanted “WSM” and pulled some strings. We went on air

with a onekilowatt Western Electric transmitter. It had a radius of maybe one hundred or one hundred-and-fifty miles. I think

Craig’s goal was to reach the states that National Life operated in.

WSM Studio A. Jack DeWitt: “It was the only studio we had for a long time. There was a door from the studio to the hall and

a door from the hall to the control room, and glass panels between the studio and control room.”

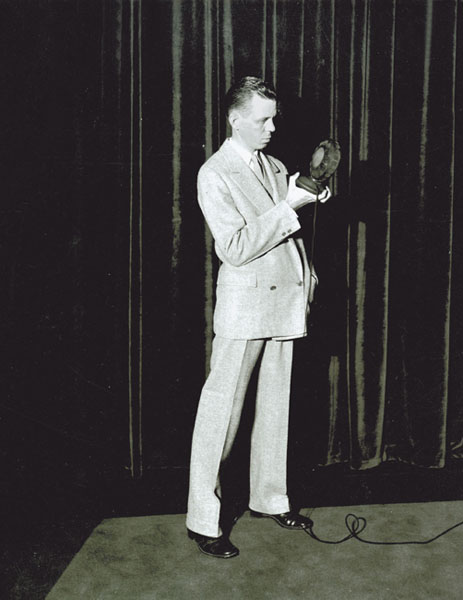

left: “Can you hear me now?” Aaron Shelton, WSM engineer, in the station’s remote broadcast truck. WSM began remote broadcasts

the first day it went on the air.

right: Beasley Smith’s Andrew Jackson Orchestra was one of the groups to perform during WSM’s opening ceremonies. After the

Opry made Nashville the country music capital, Smith jumped onto the bandwagon by cowriting Roy Acuff’s hit “Night Train to

Memphis.”