The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City (22 page)

Read The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City Online

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Rome

BOOK: The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City

5.29Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The morning was still young when Natalis was hustled into the Servilian Gardens. Scaevinus had been taken into another room by the time that Natalis was brought before Nero. Natalis was asked what he had discussed with Scaevinus in their secret meeting. Natalis’ version of what transpired turned out to be completely different from the one given by Scaevinus only minutes before. Nero, knowing that at least one of the men was lying, ordered the pair put in chains and questioned further.

Manacles were placed on the wrists of Scaevinus and Natalis, who were hustled away to the Praetorian barracks on the other side of the city. For the first time in almost a year, Praetorian Prefect Tigellinus once more took center stage. Sidelined by Nero since the Great Fire—perhaps because the fire’s second stage had erupted on Tigellinus’ property and Nero had subsequently kept the prefect at arm’s length in an attempt to dispel the rumors that he had been responsible for the fire—Tigellinus was now called on by Nero to do what he did best and deal with traitors in his own inimitable style.

Taking charge of the prisoners Scaevinus and Natalis at the barracks, Tigellinus showed them his favorite toy, the rack. The very sight of the torture device was enough to unlock the lips of both men. First, Natalis, under separate questioning and promised immunity if he gave the names of other conspirators, confessed the details of the plot and named Piso as the head of it, also mentioning his meetings with Seneca on Piso’s behalf. These names were put to Scaevinus. Believing that Natalis had revealed all, he confirmed these names, admitted his part in the conspiracy, and then proceeded to name all the other civilian conspirators. Yet neither he nor Natalis named any of the tribunes or centurions of the Praetorian Cohorts who were party to the plot. It is likely that in doing so, both men were hoping that the Praetorian officers would now act, lead a revolt of their troops against Nero, and free the accused men.

Word of the arrest of Scaevinus and Natalis had swept through the city that morning. Even as Scaevinus and Natalis were still being questioned at the Servilian Gardens, Gaius Piso received the news from several worried fellow conspirators. The plot was exposed, or soon would be, as Piso knew all too well, for neither Scaevinus nor Natalis had a reputation for courage, and both could be expected to reveal all through torture or the offer of reward. Piso’s friends urged him to gather up his supporters and hurry to the Praetorian barracks, or mount the Rostra in the Forum and take the initiative.

“Test the feelings of the soldiers and of the people,” said one conspirator. He believed that by making the movement against Nero public, Piso would attract many more followers. Nero had yet to call out his guards, he said, and there was still time to overwhelm the emperor before he realized the scope of the conspiracy.

13

13

Another of Piso’s friends felt that it was too late—troops would be on their way to arrest him at any moment. He counseled Piso to take his own life while he had the chance. “Justify your life to your ancestors and descendants,” he urged.

14

14

Piso, undecided as to which course to follow, went out into the street to gauge the public mood. Yet while the news of the arrests of Scaevinus and Natalis was now common knowledge, there was no sense of excitement or of panic in the streets, no talk of joining the movement against Nero, or of the military’s coming out against the emperor. Daily life was continuing as normal. And Piso knew at once that the conspiracy was doomed to fail. Going back into his house, he closed his doors, ordered his servants to bring him wine, and sent for his secretary.

As Piso waited, he dictated a new will in which he heaped praise on Nero and left a portion of his estate to the emperor. This was designed to ensure that Nero would allow Piso’s wife Atria to at least retain her dowry, as Roman law provided in the case of a normal death. Otherwise, the imperial treasury could confiscate Piso’s entire estate, the usual outcome when a man was convicted of treason.

In quick succession, Praetorian detachments burst into one house and apartment after another across the city. Named conspirators were hauled in for questioning, as were their servants. Most of the arrested men confessed their part in the plot, sooner or later, but three of the accused steadfastly maintained their innocence—Lucan the young poet, Quintianus the senator, and Nero’s erstwhile friend Senecio the Equestrian, the conspirators’ “inside man.” Their attitude changed when they were offered immunity from prosecution if they admitted their complicity and each gave the name of at least one co-conspirator. All three now confessed. Lucan named his mother Atilla as his co-conspirator. The other two men named their best friends. Lucan seemed to believe that if he named his mother, Nero would not stoop to arresting her, which in fact proved to be the case. Lucan and the other two were then set free and allowed to go home.

Nero now remembered, or was reminded, that the freedwoman Epicharis was still being held in custody, and he ordered that she be questioned a second time, this time on the rack. Tigellinus’ men were quick to employ their skills as torturers. Epicharis was placed on the rack, face down, with her arms and legs stretched wide. She was “scourged”—whipped. Red-hot irons were applied to her skin. But she steadfastly denied the charge that she was involved with this conspiracy. So, she was stretched on the rack until her legs were dislocated. Still she denied any complicity and refused to implicate anyone else. By the end of the day, she was cast into a cell in agony, but without having given in to her torturers.

A detachment of Praetorians arrived outside Gaius Piso’s closed doors. These troops were all men from outlying parts of southern Italy who had only joined the Praetorian Cohorts in the most recent draft. The older enlisted men, who had served under the Praetorian standard for many years, were “actually imbued with a liking” for Nero, according to Tacitus.

15

But Nero was worried that those older men might have grown some attachment to the popular Piso after living at the capital for so many years. Recent recruits, youngsters from outside the capital, would not know Piso. So, Nero had given specific instructions that new men be sent to arrest Piso.

15

But Nero was worried that those older men might have grown some attachment to the popular Piso after living at the capital for so many years. Recent recruits, youngsters from outside the capital, would not know Piso. So, Nero had given specific instructions that new men be sent to arrest Piso.

The tribune in command of the detachment was informed by Piso’s staff that their master had just this minute severed the arteries of his arms and would soon be dead. The officer decided to allow Piso the dignity of a self-inflicted death; his troops would remain at the house until it was confirmed that Piso was dead. The officer would then enter and view Piso’s corpse. Drawing his sword, he would cleave off the dead senator’s head. That head would be taken to the Servilian Gardens as proof of Piso’s demise.

Nero, “more and more alarmed” as the plot unfolded before his eyes and more and more names were added to the list of conspirators, ordered the size of his bodyguard multiplied and the city brought under military control.

16

All cohorts of the German Guard stationed at their barracks west of the Tiber were called to arms. The fourteen Praetorian Cohorts were also summoned to duty. Praetorian detachments marched to the guard towers at all the city gates and occupied them, augmenting the small City Cohort detachments on duty at the gates. Armed with a list of suspects, the Praetorians stopped and questioned all persons leaving the capital. Other cohorts marched from the city to take up station along the bank of the Tiber River to prevent accused men from escaping by water.

16

All cohorts of the German Guard stationed at their barracks west of the Tiber were called to arms. The fourteen Praetorian Cohorts were also summoned to duty. Praetorian detachments marched to the guard towers at all the city gates and occupied them, augmenting the small City Cohort detachments on duty at the gates. Armed with a list of suspects, the Praetorians stopped and questioned all persons leaving the capital. Other cohorts marched from the city to take up station along the bank of the Tiber River to prevent accused men from escaping by water.

Squadrons from the Praetorian Cavalry galloped from the city and down the Via Ostiensis to the coast, where, at Ostia, they joined the men of the 17th Cohort of the City Guard, which was then stationed at Ostia, to watch the docks for wanted men. To seek out suspects who were vacationing away from the capital, more cavalry pounded along the highways to outlying towns and villages, where they were joined by men from the German Cohorts, who were at that time stationed outside Rome. According to Tacitus, Nero trusted the German troops more than he did the citizen soldiers of the Praetorian Cohorts, and he now deliberately added squads of Germans to the Praetorian units, to ensure that the Praetorians did their duty and did not fail to round up members of the assassination conspiracy.

17

17

Nero had historical reasons for doing this. Augustus had founded the German Cohorts with the conviction that these foreign troops, who did not hold Roman citizenship, would be unlikely to join any uprising against the throne, which proved to be the case. For the same reason, Tiberius had salted troops from the German Cohorts among Praetorian troops sent to put down a legion mutiny in Dalmatia early in his reign.

As Nero’s troops now spread far and wide, Nero assigned a Praetorian tribune, Gavius Silvanus, the task of locating and questioning the former chief secretary, Lucius Seneca. In particular, Silvanus was under orders to put to Seneca the words of confessed conspirator Natalis who implied that Seneca had been aware of the assassination plot, and to demand to know if Natalis’ claim was truthful. Silvanus strode away to fulfill his assignment. As had been the case for many months, Seneca was outside Rome. But unbeknownst to Nero, there was at least one Praetorian tribune who knew precisely where to find the former chief secretary. Either much of the day would pass before Silvanus obtained that information from his colleague, or he would stall for hours before acting on the information.

Unlike Seneca, the consul-designate Plautius Lateranus was close at hand and had no time to run before the Praetorians burst in on him. Several other well-placed conspirators had given Lateranus’ name, and his fate was sealed. His arrest took place so quickly that Lateranus did not have time to take his own life or even to give his children a parting embrace. Tribune Statius Proximus was in charge of the troops who arrested Lateranus. The prisoner said nothing as he was hustled out the door with chains on his wrists, ankles, and neck and then dragged to a place outside the city customarily used for the execution of slaves. But Lateranus knew that Tribune Proximus was also a member of the conspiracy, and the prisoner was probably hoping that at the last moment, the tribune would save him.

Lateranus had no such luck. Tribune Proximus was only interested in saving his own skin and was in a hurry to silence the high-ranking conspirator. Pressed to his knees, Lateranus was told to straighten his neck. Proximus drew his sword and, with one solid, two-handed blow, took off the consul-elect’s head.

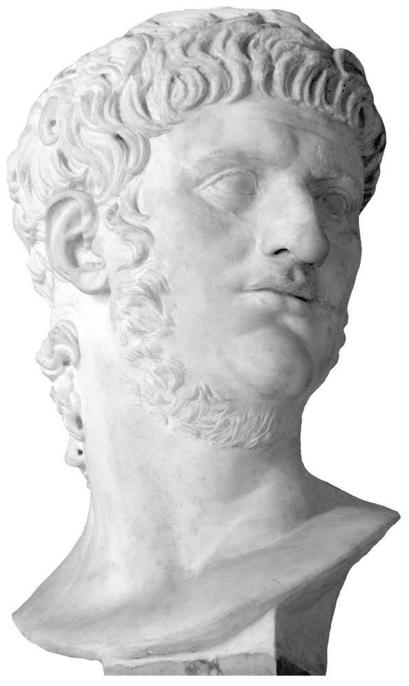

NERO, emperor at sixteen, was overweight and just starting to express his artistic tendencies by the time of the Great Fire of Rome, ten years after he ascended the throne. (Capitoline Museum)

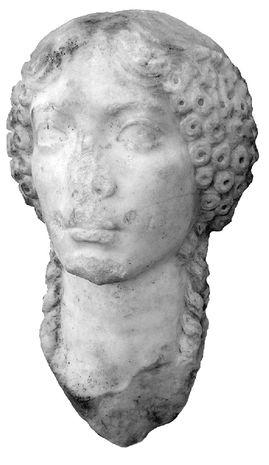

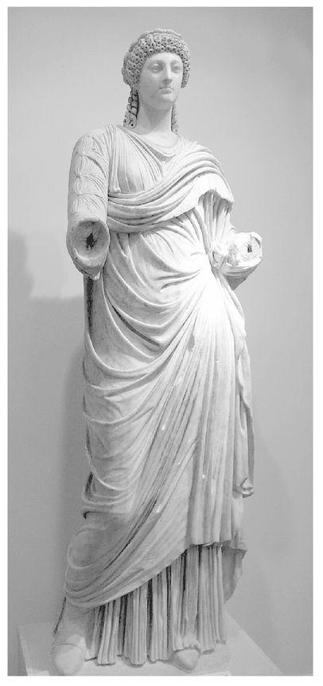

AGRIPPINA THE YOUNGER, Nero’s ultra-ambitious mother, married the emperor Claudius then murdered him to put Nero on the throne, only for Nero to engineer her death. (Archaeological Museum of Istria, Pula)

Other books

Victory Point by Ed Darack

Lundyn Bridges by Patrice Johnson

Wild: Dark Riders Motorcycle Club by Elsa Day

El fantasma de Canterville by Oscar Wilde

A Spell of Winter by Helen Dunmore

The Flesh Eaters by L. A. Morse

Four Feet Tall and Rising by Shorty Rossi

Giving It Up for the Gods by Kryssie Fortune

Forgotten Sea by Virginia Kantra

Chocolate Chocolate Moons by JACKIE KINGON