The Great Fossil Enigma (22 page)

Read The Great Fossil Enigma Online

Authors: Simon J. Knell

6.1.

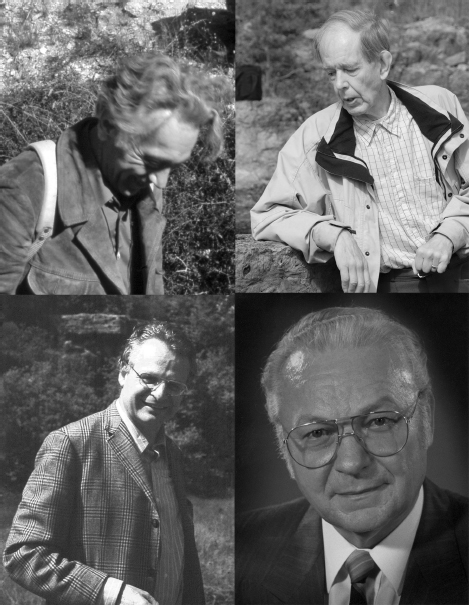

Four harbingers of spring, captured in later life.

Clockwise from top left:

Otto Walliser, Maurits Lindström, Willi Ziegler, and Klaus Müller Photos respectively: Dick Aldridge; Helje Pärnaste; Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung; John Huddle, courtesy of John Repetski.

A school of conodont studies was established at Marburg in Beckmann's wake in which Willi Ziegler, Günther Bischoff, Ursula Tatge, Otto Walliser, Hans Bender, Dieter Stoppel, Reinhold Huckriede, Peter Bender, Hans Wittekindt, and others came to work on these fossils. It became a site of intensive research activity. Beckmann's influence spread to all corners of the soon-to-be-divided country. Dietrich Sannemann at Würzburg, for example, was the first to confirm Beckmann's results with his own pioneering study.

18

At Humboldt University, Joachim Helms, an assistant to Gross, began working on the conodonts of Müller's Thuringia around 1958.

In Marburg, Bischoff and Ziegler began as PhD students under the supervision of Professor Carl Walter Kockel, who, although an excellent tutor, actually knew little of conodonts. Bischoff took inspiration from Hermann Schmidt, then a Göttingen professor, and collected limestone samples from the Devonian-Carboniferous boundary under Schmidt's guidance during the Arnsberg conference of the German Geological Society in 1954. Bischoff was astonished by the wealth and variety of conodont material this produced, and at the clear faunal change that appeared to separate the Devonian from the Carboniferous.

19

Using this material and the security of the cephalopod fossils that already divided up these rocks, he could, unlike American workers only a few years before, be certain of this change.

While Bischoff worked at the top of the Devonian, Ziegler began an assault on the poorer faunas of the Lower and Middle Devonian. Before long the two men were working closely together and attempting to create their own parallel chronology to mirror that based on cephalopods. Throughout the mid- to late 1950s, the combined effort of these young Marburg scientists continued to reap results and the foundations were laid for major developments in the following decade.

In 1958, a position came up for a conodont specialist at the Geological Survey at Krefeld. Müller was approached, but hearing that the organization had no director and was moribund, he declined. Ziegler was less choosy, and already rather more attached to conodonts than Müller, and he accepted the post. Driven to succeed whatever the organization's circumstances, Ziegler's energy and single-mindedness, applied in a full-time position, left Müller standing. Ziegler probably understood that it would permit him to outcompete those who shared his ambitions. Müller now looked on helplessly as the door shut. The German, and with it possibly the world's, Devonian now belonged to Ziegler.

Müller's survival instincts kicked in. Better to enter an uncompetitive field than to fight; Müller was not much of a fighter. Perhaps he would be able to do in the Silurian what he had planned for the Devonian? Müller turned to the excellent Silurian sections in the Carnic Alps on the border between Austria and Italy. This field work also had the advantage of altitude, so beneficial to his ongoing health problems. But he had not been collecting long before he discovered he was not alone. Otto Walliser shared Müller's new ambitions.

Like Müller, although somewhat younger, Walliser was a survivor of the war. He had imagined a career in the realm of living plants â in his case forestry science â but the university in his home town of Tübingen offered no such course. However, geology seemed to fit with his nature-loving instincts, and he soon developed the ambition of becoming a museum curator. Tübingen also had the distinction of being home to Schindewolf, from whom Walliser would learn some of his geology. On completing his degree, Walliser moved to Marburg. He was already becoming a specialist in Lower Jurassic ammonites, but he was also aware that he was entering the new German center for conodont studies. And as he was to be senior to the younger Ziegler, Bischoff, and Tatge, he thought it judicious to take an interest in these fossils. With the Devonian and Triassic niches already filled by those he was joining, he fixed his attention on the Silurian. From his first trip to the Frankenwald, he returned with a single sample that proved by far the richest in conodonts in his whole career. This demonstrated the potential, and so he began working on the Silurian of the Carnic Alps.

Walliser had worked on these rocks for a year before Müller appeared in search of upland solitude. For both men this was a problem. Müller had funding from the national geological society but now found himself in the embarrassing position of possessing a grant for a project that lacked the scientific novelty he had claimed. Walliser was already considerably more advanced in his studies. Müller asserted his right to proceed on the basis of the support he had been given. Walliser claimed the advantage of being the first and of being self-funded; he was not going to give way. Someone suggested the compromise of collaboration, but Müller, who kept his tuberculosis hidden, knew his health would not take it and declined. He knew Walliser was strong and an exceptional field man. In the end a compromise was negotiated: Müller agreed to deal with the simple cones and Walliser with the rest. Walliser gave Müller all his simple cones, but Müller failed to keep his part of the bargain. Walliser then had no opportunity to do the work himself. The two men remained on bad terms throughout their careers. Only in retirement, decades later, did Müller write to Walliser to express his regrets.

20

The outcome for science of this face-off was, however, hugely positive for both men. Müller did not, in the end, stand his ground and was forced to drop down even deeper in the stratigraphic column, into the Cambrian, which for most conodont workers was completely off the radar. Here he had space to make the most remarkable discoveries and achieve real distinction. In 1975, Müller, now perceived as a Cambrian specialist, found his life change again when he accidentally discovered the finely preserved “Orsten” fossils. Then fifty years old, he effectively gave up conodonts to pursue these new and extraordinary fossils, and a new community of researchers grew up around him. Fossils preserved in three dimensions and in exquisite detail, he was able to challenge the interpretation of one of paleontology's most iconic objects, the tiny and strikingly odd trilobite,

Agnostus.

Müller felt he proved, on the basis of remarkably preserved soft parts, that this famous fossil was not a trilobite at all.

21

As for Walliser, he soon had the Silurian to himself and in a few years had singlehandedly tamed it. He in time became drawn to far bigger questions concerning the history of the planet. We shall return to both these men.

Before 1950, Sweden had played little role in the development of conodont studies, and in common with much of the rest of Europe, it barely knew these fossils. Among these earlier Swedish workers was Assar Hadding, who had described a dozen conodonts in his 1913 doctoral thesis on graptolites. These fossils had been found in Ordovician rocks not far from Lund, where Hadding was, from 1947, rector of the university and a prominent figure in Swedish geology. A stratigraphically isolated fauna, Hadding's finds had no real scientific impact, but Swedish geologists became aware that there was a group of fossils they had overlooked.

The Swedish workers who entered the science in the 1950s invariably possessed botanical roots. This interest in plants and their taxonomy owed everything to Sweden's great hero, Carl Linnaeus. So it was that Sweden's conodont pioneer of the new generation, Maurits Lindström, was required as a schoolboy to collect and curate a herbarium, along with every other twelve year old. He was expected to know and to be able to identify some twelve hundred plant species. Stig Bergström, who became established as a leading conodont worker in the early 1960s, began as a particularly outstanding botanist. “But when he came across the conodonts he found in them such potential and such beauty,” Lindström later reflected, that Bergström decided “that this should be it!”

22

Lennart Jeppsson, a still later worker, also came to this science through botany. We shall come to these younger men in due course. For Lindström, plants were not a first love, but they were a means to gain rapid entry into university, and this he did.

As a schoolboy, Lindström had made a small study of the Middle Ordovician, not far from where Hadding had collected his material. He wrote this up and presented it to his biology teacher, who was completely amazed by it. Encouraged, he continued to work on it after 1950, publishing it in 1953 when nineteen or twenty years old. Lindström was a schoolboy paleontologist.

In 1949, and still in his mid-teens, he had the opportunity to study geology under the distinguished Swedish stratigrapher J. E. Hede, where he now found himself by far the youngest in a class of just three. His compatriots were, to his eyes, like uncles; he still considered himself merely a schoolboy. Hede was by this stage rather elderly and his method of teaching rather archaic; he would read out the essential content of a paper published perhaps twenty years before, showing illustrations and drawing beds and listing fossils, and expect the students to make copious notes. Lindström remembers clearly the fleeting moment when the conodont appeared mainly for its political message, as this was a university where Hadding ruled: Hede said, “Conodonts are probably worm jaws but one can generalise and say that they are essentially anything small and spiny described by an incompetent palaeontologist!” Lindström soaked up this mass of geological information undeterred by the formality of its delivery. Now he at least knew of the conodonts, but he was yet to

really

know them.

Around 1950, Lindström came across papers by Russian and Indian workers discussing the sensational discovery of very small plant fragments, including wood, in rocks of Cambrian age.

23

These were puzzling discoveries of things that had no right to occur in rocks so old. Lindström was encouraged to begin his own investigations. In his student room, he set up a small laboratory and began dissolving bituminous limestones with hydrochloric acid. The stench of acid and bitumen was everywhere. Among the fossils he found were some odd spiny fragments, which were clearly not plant remains. He took these to Sweden's leading micropaleontologist, Fritz Brotzen, in Stockholm. A fugitive Prussian Jew and German autocrat, Brotzen told Lindström, in his strange Swedish, that they were probably trilobite fragments and not very interesting. He advised Lindström to take up the study of fossil fishes instead â fossil fishes then being a Stockholm strength â and then sent him to see Erik Stensiö, the country's leading fish paleontologist. Stensiö presented Lindström to his assistant, Erik Jarvik, who later became Stensiö's successor and who was then working on the structure of the teeth of primitive fishes from Gotland. Jarvik had extracted these teeth from limestone using acetic acid, after which he thin-sectioned them and studied their microscopic structure. Lindström was impressed. Jarvik showed interest in Lindström's fossils but advised him, “Use 10% acetic acid and you will experience wonders.”