The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia

Read The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia Online

Authors: Peter Hopkirk

Tags: #Non-fiction, #Travel, ##genre, #Politics, #War, #History

THE GREAT GAME

On Secret Service in High Asia

PETER HOPKIRK

‘Now I shall go far and far into the North,

playing the Great Game . . .’

Rudyard Kipling,

Kim,

1901

First published in Great Britain in 1990 by John Murray (Publishers)

An Hachette UK Company

© Peter Hopkirk 1990, 2006

The right of Peter Hopkirk to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978-1-84854-477-2

Book ISBN 978-0-7195-6447-5

John Murray (Publishers)

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For Kath

CONTENTS

3. Rehearsal for the Great Game

6. The First of the Russian Players

12. The Greatest Fortress in the World

21. The Last Hours of Conolly and Stoddart

23. The Great Russian Advance Begins

26. The Feel of Cold Steel Across His Throat

27. ‘A Physician from the North’

28. Captain Burnaby’s Ride to Khiva

29. Bloodbath at the Bala Hissar

30. The Last Stand of the Turcomans

32. The Railway Race to the East

34. Flashpoint in the High Pamirs

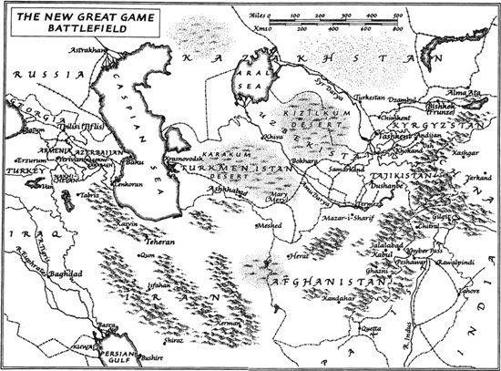

MAPS

The Battlefield of the New Great Game

Afghanistan and the N.W. Frontier

FOREWORD

THE NEW GREAT GAME

Since this book was first written, sixteen years ago, momentous events have convulsed Great Game country, adding considerably to the significance of my narrative. Suddenly, after many years of almost total obscurity, Central Asia is once again in the headlines, a position it frequently occupied during the nineteenth century, at the height of the old Great Game between Tsarist Russia and Victorian Britain.

With the sudden and dramatic collapse of Communism in 1991, and the breaking up of the Soviet empire, there sprang up almost overnight five entirely new countries – eight if you include the Caucasus region. At first, even those with long experience of Central Asia had difficulty in familiarizing themselves with this new geographical and political jigsaw puzzle – not to mention getting their tongues around such romanizations as Kyrgyzstan.

It had all been so much simpler when the entire region was just called Soviet Central Asia. A single visa, if you could get one, took you from Baku to Bokhara, from Tbilisi to Tashkent, with Moscow and Leningrad thrown in. Also, though here I can only speak for myself, travelling there at the height of the Cold War was always an adventure, like sneaking behind enemy lines, particularly if one was engaged in covert research.

Following Moscow’s abrupt exit, Western embassies began to open up in brand-new capital cities, Soviet names were expunged from the map, and history books hastily rewritten, while foreign companies stepped in eagerly to fill the commercial and economic vacuum. For it was no secret that in Central Asia lay some of the last great prizes of the twentieth century. These included fabulous oil and gas reserves, together with rich hoards of gold, silver, copper, zinc, lead and iron ore, not to mention crucial oil-pipeline routes. So fierce was the competition that political analysts and headline writers in the West quickly began to speak of a ‘new Great Game’, as rival foreign powers and multinational companies fought for influence there. Some too had strategic and political agendas.

But the sudden lurch from Communism to free-for-all capitalism has not been achieved without a heavy toll. Small but vicious conflicts – in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, not to mention in neighbouring parts of southern Russia, such as Chechnya and North Ossetia – have since convulsed this highly volatile region as rival factions jockeyed for power.

As I write this, things have gone momentarily quiet there. But not so elsewhere on the old Great Game battlefield. In Afghanistan, so long at the epicentre of the century-long Anglo-Russian confrontation, bloodshed seems almost endemic. In 1979, the Russians moved in 100,000 troops to support their puppet government. But after a barbaric ten-year conflict, they were humiliatingly forced to withdraw. They left behind them their former puppet President, General Mohammed Najibullah, who four years later fell into the hands of the triumphant Taliban when Kabul surrendered to them. Dragged from the UN compound where he had been given sanctuary, he was brutally beaten, castrated, then strung up publicly. Gruesome photographs of him hanging there were splashed on the front pages of the world’s newspapers. It was also reported that he had been translating

The Great Game

into Pashto, telling friends that every Afghan should be made to read it so that the terrible mistakes of the past would never be repeated.

Next to follow the Russians into Afghanistan, in 2001, were US, British, Canadian, Dutch and other NATO troops. This sprang from fears that further 9/11-type attacks on Western targets might be planned from secret al-Qaeda bases there. As well as destroying these, the NATO-led force was tasked with maintaining an uneasy peace, preparing the way for elections, eliminating the drug barons and helping with reconstruction. The UK is currently planning to despatch more troops there to help with this nightmarish – if not impossible – task, which has so far cost the lives of 22 British servicemen – an average of one every eight days. At the time of writing, the outcome of the present brutal struggle in Afghanistan is impossible to foresee.

The two most powerful players in the ‘new Great Game’, the USA and Russia, are both anxious to keep Central Asia in a peaceful and cooperative state in order to preserve their access to its rich gas and oil supplies. Indeed, Russia’s new power on the world stage is heavily dependent on control of the pipelines. The thought of any of the new Central Asian states following the example of Iran with its heady and alarming mix of oil, fundamentalism and possible nuclear weapons, is viewed as hair-raising in Washington and Moscow – though happily at present this seems a remote possibility.

Besides the Americans and Russians, other regional powers, notably China, India and Pakistan, are looking on with intense self-interest and concern. For the collapse of Russian rule in Central Asia has tossed the area back into the melting pot of history. Almost anything could happen there now and only a brave or foolish man would predict its future. For this reason I have not attempted to update my original narrative beyond adding this brief foreword. Among all the uncertainties, however, one thing seems certain. For good or ill, Central Asia is back in the thick of the news once more, and likely to remain there for a long time to come.

Peter Hopkirk

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many years ago, when a subaltern of 19, I read Fitzroy Maclean’s classic work of Central Asian travel,

Eastern Approaches.

This heady tale of high adventure and politics, set in the Caucasus and Turkestan during the darkest years of Stalinist rule, had a powerful effect on me, and no doubt on many others. From that moment onwards I devoured everything I could lay hands on dealing with Central Asia, and as soon as it was opened to foreigners I began to travel there. Thus, if only indirectly, Sir Fitzroy is partly responsible – some might say to blame – for the six books, including this latest one, which I have myself written on Central Asia. I therefore owe him a considerable debt of gratitude for first setting my footsteps in the direction of Tbilisi and Tashkent, Kashgar and Khotan. No finer book than

Eastern Approaches

has yet been written about Central Asia, and even today I cannot pick it up without a frisson of excitement.