The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (5 page)

Read The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris Online

Authors: David Mccullough

Tags: #Physicians, #Intellectuals - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Artists - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Physicians - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris, #Americans - France - Paris, #United States - Relations - France - Paris, #Americans - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #France, #Paris (France) - Intellectual Life - 19th Century, #Intellectuals, #Authors; American, #Americans, #19th Century, #Artists, #Authors; American - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris (France) - Relations - United States, #Paris (France), #Biography, #History

Even without the “impertinences,” the whole requirement of passports—the cost, the “vexatious ceremony” of it all—was repugnant to the Americans. In conversation with an English-speaking Frenchman, John Sanderson mentioned that no one carried a passport in America, not even foreign visitors. The man wondered how there could be any personal security that way. To Sanderson this seemed only to illustrate that when one was used to seeing things done in a certain way, one found it hard to conceive the possibility of their being done any other way.

Having at last attended to all the requirements for entry into France, Sanderson went straightaway to the nearest church “to pay the Virgin Mary the pound of candles I owed for my preservation at sea.”

Most of the travelers preferred to wait a day or more at Le Havre, to rest and look about before pushing on. Though nothing was like what they were accustomed to, what struck them most was how exceedingly old everything appeared. It was a look many did not like. Not at first. Charles Sumner was one of the exceptions. With his love of history, he responded

immediately and enthusiastically to the sense of a long past all about him. “Everything was old. … Every building I passed seemed to have its history.” He saw only one street with a sidewalk. Most streets were slick with mud and uncomfortable to the feet. Men and women clattered by in wooden shoes, no different from what their grandparents had worn. It was of no matter, he thought. Here whatever was long established was best, while at home nothing was “beyond the reach of change and experiment.” At home there was “none of the prestige of age” about anything.

From Le Havre to Paris was a southeast journey of 110 miles, traveled by diligence, an immense cumbersome-looking vehicle—the equivalent of two and a half stagecoaches in one—which, as said, sacrificed beauty for convenience. It had room for fifteen passengers in three “apart-ments”—three in the front in the

coupe

, six in the

intérieur

, and six more in the

rotonde

in the rear. Each of these sections was separate from the others, thereby dividing the rich, the middling, and the poor. “If you feel very aristocratic,” wrote John Sanderson, “you take the whole coupe to yourself, or yourself and lady, and you can be as private as you please.” There were places as well for three more passengers “aloft,” on top, where the baggage was piled and where the driver, the

conducteur

, maintained absolute command.

The huge lumbering affair, capable of carrying three tons of passengers and baggage, was pulled by five horses, three abreast in front, two abreast just behind them. On one of the pair a mounted

postillon

in high black boots cracked the whip. Top speed under way was seven miles an hour, which meant the trip to Paris, with stops en route, took about twenty-four hours.

Once under way, before dawn, the Americans found the roads unexpectedly good—wide, smooth, hard, free from stones—and their swaying conveyance surprisingly comfortable. With the onset of first light, most of them thoroughly enjoyed the passing scenery, as they rolled through level farm country along the valley of the Seine, the river in view much of the way, broad and winding—ever winding—and dotted with islands.

Just to be heading away from the sea, to be immersed in a beautiful landscape again, to hear the sound of crows, was such a welcome change, and all to be seen so very appealing, a land of peace and plenty, every field

perfectly cultivated, hillsides bordering the river highlighted by white limestone cliffs, every village and distant château so indisputably ancient and picturesque.

I looked at the constantly occurring ruins of the old priories, and the magnificent and still used churches [wrote Nathaniel Willis], and my blood tingled in my veins, as I saw in the stepping stones at their doors, cavities that the sandals of monks, and the iron-shod feet of knights in armor a thousand years ago, had trodden and helped to wear and the stone cross over the threshold that hundreds of generations had gazed upon and passed under.

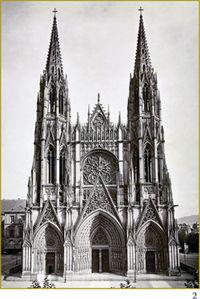

Most memorable on the overland trip was a stop at Rouen, halfway to Paris, to see the great cathedral at the center of the town. The Americans had never beheld anything remotely comparable. It was their first encounter with a Gothic masterpiece, indeed with one of the glories of France, a structure built of limestone and far more monumental, not to say centuries older, than any they had ever seen.

The largest building in the United States at the time was the Capitol in Washington. Even the most venerable houses and churches at home, north or south, dated back only to the mid seventeenth century. So historic a landmark as Philadelphia’s Independence Hall was not yet a hundred years old.

An iron spire added to the cathedral at Rouen in 1822 reached upward 440 feet, fully 300 feet higher than the Capitol in Washington, and the cathedral had its origins in the early thirteenth century—or more than two hundred years before Columbus set sail for America—and work on it had continued for three centuries.

The decorative carvings and innumerable statues framing the outside of the main doorways were, in themselves, an unprecedented experience. In all America at the time there were no stone sculptures adorning the exteriors of buildings old or new. Then within, the long nave soared more than 90 feet above the stone floor.

It was a first encounter with a great Catholic shrine, with its immense

scale and elaborate evocations of sainthood and ancient sanctions, and for the Americans, virtually all of whom were Protestants, it was a surprisingly emotional experience. Filling pages of her journal, Emma Willard would struggle to find words equal to the “inexpressible magic,” the “sublimity” she felt.

I had heard of fifty or a hundred years being spent in the erection of a building, and I had often wondered how it could be; but when I saw even the outside of this majestic and venerable temple, the doubt ceased. It was all of curious and elegantly carved stonework, now of a dark grey, like some ancient gravestone that you may see in our oldest graveyards. Thousands of saints and angels there stood in silence, with voiceless harps; or spread forever their moveless wings—half issuing in bold relief from mimic clouds of stone. But when I entered the interior, and saw by the yet dim and shadowy light, the long, long, aisles—the high raised vaults—the immense pillars which supported them … my mind was smitten with a feeling of sublimity almost too intense for mortality. I stood and gazed, and as the light increased, and my observation became more minute, a new creation seemed rising to my view—of saints and martyrs mimicked by the painter or sculptor—often clad in the solemn stole of the monk or nun, and sometimes in the habiliments of the grave. The infant Savior with his virgin mother—the crucified Redeemer—adoring angels, and martyred saints were all around—and unearthly lights gleaming from the many rainbow-colored windows, and brightening as the day advanced, gave a solemn inexpressible magic to the scene.

Charles Sumner could hardly contain his rapture. Never had a work of architecture had such powerful effect on him. The cathedral was “the great lion of the north of France … transcending all that my imagination had pictured.” He had already read much of its history. Here, he knew, lay the remains of Rollon, the first Duke of Normandy, the bones of his son,

William Longsword, of Henry II, the father of Cœur de Lion, even the heart of Lionheart himself.

And here was I, an American, whose very hemisphere had been discovered long since the foundation of this church, whose country had been settled, in comparison with this foundation, but yesterday, introduced to these remains of past centuries, treading over the dust of archbishops and cardinals, and standing before the monuments of kings. …

How often he had wondered whether such men in history had, in truth, ever lived and did what was said they had. Such fancy was now exploded.

In an account of his own first stop at Rouen and the effect of the cathedral on him and the other Americans traveling with him, James Fenimore Cooper said the common feeling among them was that it had been worth crossing the Atlantic if only to see this.

With eighty miles still to go, most travelers chose to stop over at Rouen. Others, like Nathaniel Willis, eager to be in Paris, climbed aboard a night diligence and headed on.

Great as their journey had been by sea, a greater journey had begun, as they already sensed, and from it they were to learn more, and bring back more, of infinite value to themselves and to their country than they yet knew.

French diligence (stagecoach).

The cathedral at Rouen.

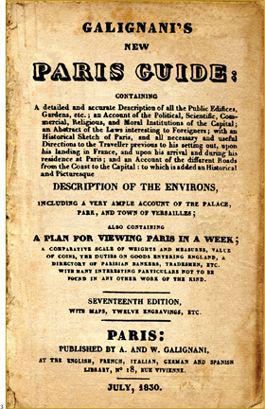

Title page of

Galignani’s New Paris Guide,

indispensable companion for newly arrived Americans.

View of the Flower Market

by Giuseppe Canella, with the Pont Neuf in the background.