The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (55 page)

Read The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris Online

Authors: David Mccullough

Tags: #Physicians, #Intellectuals - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Artists - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Physicians - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris, #Americans - France - Paris, #United States - Relations - France - Paris, #Americans - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #France, #Paris (France) - Intellectual Life - 19th Century, #Intellectuals, #Authors; American, #Americans, #19th Century, #Artists, #Authors; American - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris (France) - Relations - United States, #Paris (France), #Biography, #History

In the privacy of his diary, on January 18, Washburne wrote, “I am more and more convinced that we can only be taken by starvation.” The weight of despair had never been worse. “Four months of siege today and where has all this gone to? It seems to me as if I had been buried alive. I have accomplished nothing and, separated from my family and friends, cut off from communication to a great extent from the outside world, those dreary weeks might as well be struck off my existence.”

A great movement of some 100,000 troops was under way. The Paris National Guard, with little or no experience in fighting, was to launch a last, desperate sortie to the west of the city. “The ambulances have all been notified, and I shudder for the forthcoming horrors.” Some of the units had had only a few days of training.

The French novelist Edmond de Goncourt wrote of the “grandiose, soul-stirring sight” of the citizen army “marching towards the guns booming in the distance—

an army with, in its midst, grey-bearded civilians who were fathers, beardless youngsters who were sons, and in its open ranks women carrying their husband’s or their lover’s rifle slung across their backs.

The following day, as the battle raged near Saint-Cloud, Washburne and Wickham Hoffman went as far as Passy, to the historic old Château de la Muette, to observe with Jules Favre and other French officials as much as could be seen by telescope from an uppermost cupola.

One hundred thousand men are struggling to break through that circle of iron and of fire which has held them for four long, long months [Washburne wrote]. The lay of the country is such that we cannot see the theater of the conflict. … The low muttering of the distant cannon, and the rising of the smoke indicate, however, the field of carnage. The crowd of Frenchmen in the cupola were sad indeed, and we could not help feel for their anxiety.

From the château, Washburne returned to the American Ambulance, where carriages from the battlefield were arriving one after another with “loads of mutilated victims.”

They had brought in sixty-five of the wounded. … The assistants were removing their clothes all wet and clotted with blood, and surgeons were binding up their ghastly wounds.

Dr. Johnston and Gratiot told him the slaughter of French troops had been horrible, that the “whole country was literally covered with dead and wounded.”

“All Paris is on the

qui-vive

and the wildest reports are circulating,” he wrote by day’s end. “The streets are full of people, men, women, and children. Who will undertake to measure the agonies of this dreadful hour!”

The weather turned thick and foggy. Rumors spread of “trouble in the city” and of Trochu being “crazy as a bed bug.” On the morning of Sunday, January 22, the pounding of the bombardment seemed heavier than ever.

That afternoon some of the National Guard and an angry mob marched on the Hôtel de Ville once again but were confronted by troops of the Mobile Guard, who fired on them, killing five and wounding a dozen more. “And then such a scatteration,” wrote Washburne, “these wretches flying

in every direction … and in twenty minutes it was all ended.” But for the first time French troops had fired on their fellow Frenchmen.

Again he and Hoffman had made their way down the Champs-Élysées in an effort to see what was happening, but to no avail, so dense were the crowds and the numbers of troops drawn up.

“ ‘Mischief afoot,’ ” Washburne surmised in his diary that night, evoking a line from Shakespeare’s

Julius Caesar

. “The first blood has been shed and no person can tell what [a] half starved … Parisian population will do.”

Four days of continuing fog, rumors, and bombardment followed. He had never seen such gloom everywhere, he wrote on January 24. Hardly anyone was to be seen except those cutting down the great trees along the avenues. “The city is on its last legs. …”

And then it happened. The surrender of Paris—and the end of the war—was announced on the morning of Friday, January 27, 1871, the 131st day of the siege.

“ ‘Hail mighty day!’ ” wrote Washburne. “Not a gun is heard today, the most profound quiet reigns. …”

ADNESS

In the madness which prevails here, I will not undertake any prediction of what will happen. …

—

ELIHU WASHBURNE

The terms of the surrender became public on the twenty-ninth day of the new year, 1871. All troops in Paris were immediately to give up their arms. Cannon on the ramparts were to be thrown in the moats. The Germans would not enter the city for several days, and agreed to remain a brief time only. There was to be no occupation of Paris.

For France it had been the most ill-advised, disastrous war in history, with total defeat coming in little more than five months. The cost to France in young men killed and wounded in battle was 150,000. For the German Empire it was 117,000. The death toll in Paris was reported to have been 65,591, of whom 10,000 died in the hospitals. Three thousand had been killed in the battle for Paris. The infants who died in the city also numbered somewhere between 3,000 and 4,000.

By the terms of the surrender, France was subjected to a staggering war indemnity of 5 billion francs and forced to cede to Germany the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, a point of extreme humiliation to the French that was only to fester.

Emotions in Paris ranged from stoic acquiescence to abject gloom and bewilderment to burning fury, and this especially among the poor and those of the political left who had wanted to fight on and felt they had been betrayed by their own government.

“The enemy is the first to render homage to the moral strength and courage of the entire Paris population,” read the government’s own proclamation. “France is dead! Long live France!” declared the conservative paper

Le Soir

. But the liberal

Le Rappel

expressed the mood of tens of thousands that “Paris is trembling with anger.”

Olin Warner spoke for nearly every American who had been through the siege when he wrote of the utter relief he felt just to have it over. If ever again he found himself in similar circumstances, he assured his parents, he would remain no longer “than packing up of my clothes requires.”

Yet to Mary Putnam, who refused to abandon her faith in the ideal of a republic, the surrender had been unwanted and unnecessary. Paris could have held out another three months, she insisted, as did so many Parisians. “We are all furious,” she told her father in a letter written from the legation, where she had gone partly to get warm but also because she knew the letter would have a better chance of getting out.

The very gloom of the streets, shrouded day after day by a persistent, thick fog, seemed entirely in keeping.

Shipments of food, including barrels of flour from America, began arriving in increasing quantities. In a matter of weeks food of all kinds had become widely plentiful and cheaper than before the siege. Trains ran once more, people were free to come and go. News and mail from elsewhere began circulating. And the weather at last cleared. By late February, with a spell of “pleasant days,” Elihu Washburne could report that Paris was again “quite Parisian,” its “bright-hearted population” back filling the streets.

He eagerly anticipated the return of his family and, in the meantime, was being warmly commended for all he had done through the crises to help so many in distress, everyone assuming, as did he, that the worst was over. When his friends the Moultons asked what those shut up in Paris would have done without him, he answered, “Oh, I was only a post-office.” And praise was plentiful at home:

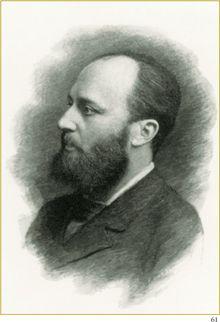

Henry James.

Mary Cassatt, self-portrait.

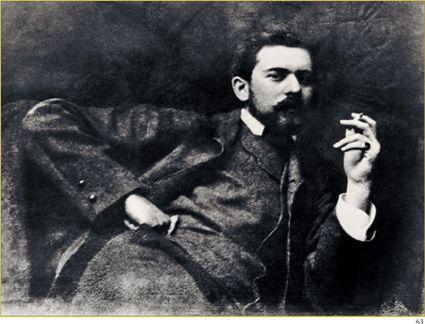

John Singer Sargent.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

by Kenyon Cox.