The Greatest Knight

Read The Greatest Knight Online

Authors: Elizabeth Chadwick

The

Greatest

Knight

The Unsung Story of

the Queen’s Champion

ELIZABETH CHADWICK

Copyright © 2005, 2009 by Elizabeth Chadwick

Cover and internal design © 2009 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover image © Larry Rostant

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, place and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Originally published in 2005 by Time Warner Books

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chadwick, Elizabeth.

The greatest knight : the unsung story of the queen’s champion / by Elizabeth Chadwick.

p. cm.

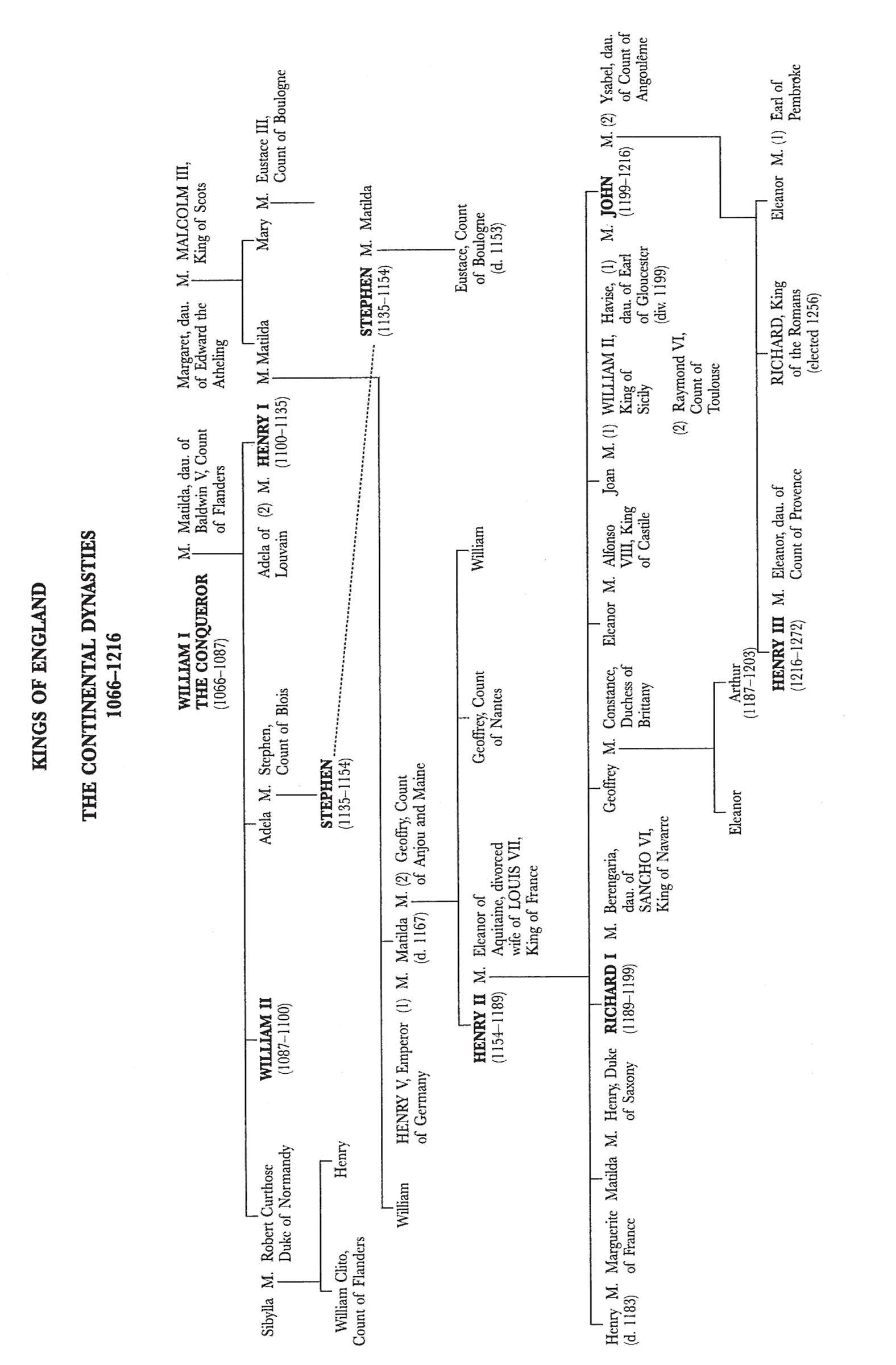

Includes bibliographical references and index.

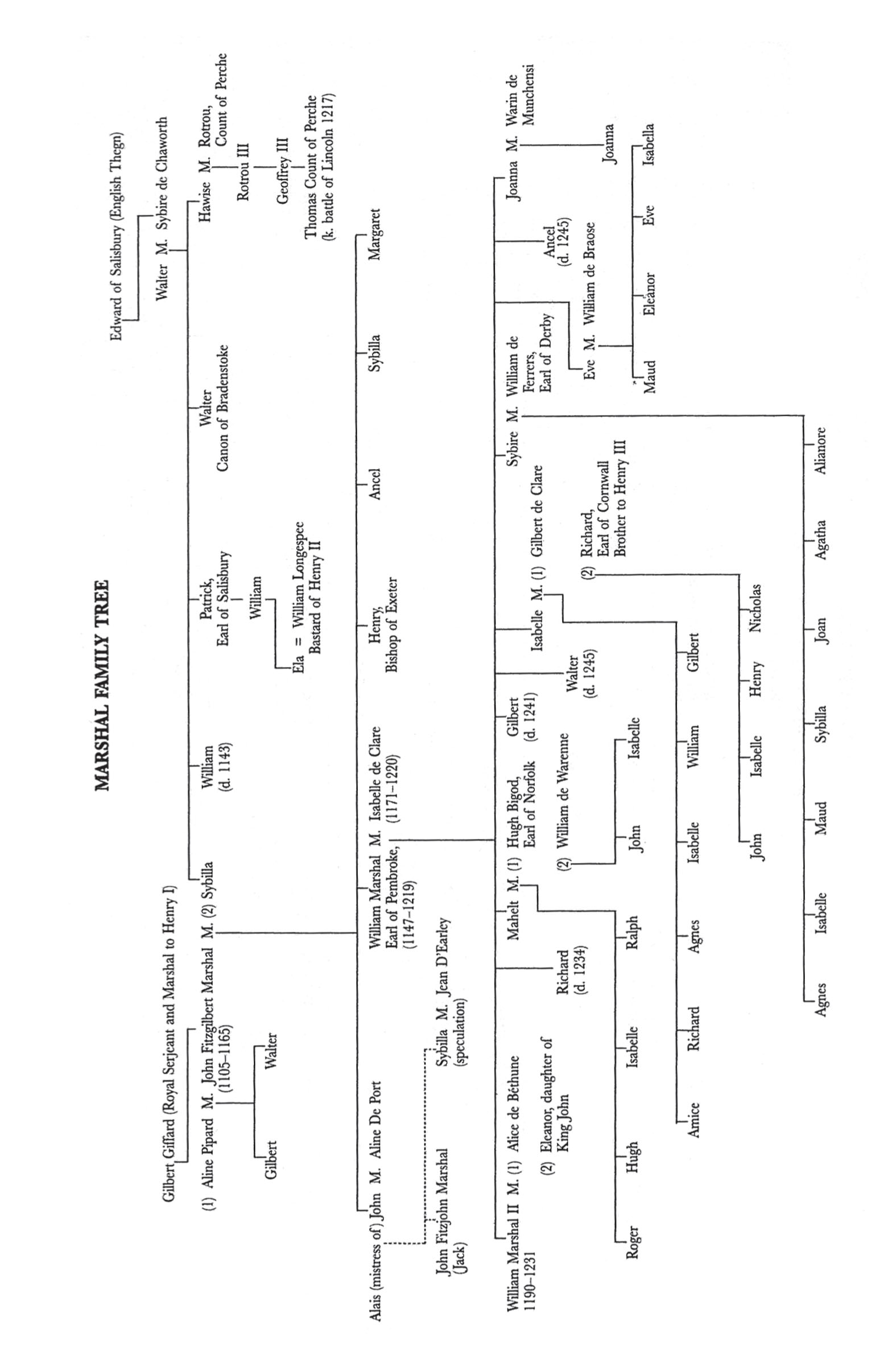

1. Pembroke, William Marshal, Earl of, 1144?-1219—Fiction. 2. Eleanor, of Aquitaine, Queen, consort of Henry II, King of England, 1122?-1204—Fiction. 3. Great Britain—History—Henry II, 1154-1189—Fiction. 4. Great Britain—Courts and courtiers—Fiction. 5. Knights and knighthood—Great Britain—Fiction. 6. Favorites, Royal—Great Britain—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6053.H245G74 2009

823’.914—dc22

2009022444

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

“Car en nostre tens n’ot il unques

En nul liu meillor chevalier”

“For in our time there was never

A better knight to be found anywhere.”

—

Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal

One

Fortress of Drincourt, Normandy, Summer 1167

In the dark hour before dawn, all the shutters in the great hall were closed against the evil vapours of the night. Under the heavy iron curfew, the fire was a quenched dragon’s eye. The forms of slumbering knights and retainers lined the walls and the air sighed with the sound of their breathing and resonated with the occasional glottal snore.

At the far end of the hall, occupying one of the less favoured places near the draughts and away from the residual gleam of the fire, a young man twitched in his sleep, his brow pleating as the vivid images of his dream took him from the restless darkness of a vast Norman castle to a smaller, intimate chamber in his family’s Hampshire keep at Ludgershall.

He was five years old, wearing his best blue tunic, and his mother was clutching him to her bosom as she exhorted him in a cracking voice to be a good boy. “Remember that I love you, William.” She squeezed him so tightly that he could hardly breathe. When she released him they both gasped, he for air, she fighting tears. “Kiss me and go with your father,” she said.

Setting his lips to her soft cheek, he inhaled her scent, sweet like new-mown hay. Suddenly he didn’t want to go and his chin began to wobble.

“Stop weeping, woman, you’re unsettling him.”

William felt his father’s hand come down on his shoulder, hard, firm, turning him away from the sun-flooded chamber and the gathered domestic household, which included his three older brothers, Walter, Gilbert, and John, all watching him with solemn eyes. John’s lip was quivering too.

“Are you ready, son?”

He looked up. Lead from a burning church roof had destroyed his father’s left eye and melted a raw trail from temple to jaw, leaving him with an angel’s visage one side and the gargoyle mask of a devil on the other. Never having known him without the scars, William accepted them without demur.

“Yes, sir,” he said and was rewarded by a kindling gleam of approval.

“Brave lad.”

In the courtyard the grooms were waiting with the horses. Setting his foot in the stirrup, John Marshal swung astride and leaned down to scoop William into the saddle before him. “Remember that you are the son of the King’s Marshal and the nephew of the Earl of Salisbury.” His father nudged his stallion’s flanks and he and his troop clattered out of the keep. William was intensely aware of his father’s broad, battle-scarred hands on the reins and the bright embroidery decorating the wrists of the tunic.

“Will I be gone a long time?” his dream self asked in a high treble.

“That depends on how long King Stephen wants to keep you.”

“Why does he want to keep me?”

“Because I made him a promise to do something and he wants you beside him until I have kept that promise.” His father’s voice was as harsh as a sword blade across a whetstone. “You are a hostage for my word of honour.”

“What sort of promise?”

William felt his father’s chest spasm and heard a grunt that was almost laughter. “The sort of promise that only a fool would ask of a madman.”

It was a strange answer and the child William twisted round to crane up at his father’s ruined face even as the grown William turned within the binding of his blanket, his frown deepening and his eyes moving rapidly beneath his closed lids. Through the mists of the dreamscape, his father’s voice faded, to be replaced by those of a man and woman in agitated conversation.

“The bastard’s gone back on his word, bolstered the keep, stuffed it to the rafters with men and supplies, shored up the breaches.” The man’s voice was raw with contempt. “He never intended to surrender.”

“What of his son?” the woman asked in an appalled whisper.

“The boy’s life is forfeit. The father says that he cares not—he still has the anvils and hammers to make more and better sons than the one he loses.”

“He does not mean it…”

The man spat. “He’s John Marshal and he’s a mad dog. Who knows what he would do. The King wants the boy.”

“But you’re not going to…you can’t!” The woman’s voice rose in horror.

“No, I’m not. That’s on the conscience of the King and the boy’s accursed father. The stew’s burning, woman; attend to your duties.”

William’s dream self was seized by the arm and dragged roughly across the vast sprawl of a battle-camp. He could smell the blue smoke of the fires, see the soldiers sharpening their weapons, and a team of mercenaries assembling what he now knew was a stone-throwing machine.

“Where are we going?” he asked.

“To the King.” The man’s face had been indistinct before but now the dream brought it sharply into focus, revealing hard, square bones thrusting against leather-brown skin. His name was Henk and he was a Flemish mercenary in the pay of King Stephen.

“Why?”

Without answering, Henk turned sharply to the right. Between the siege machine and an elaborate tent striped in blue and gold, a group of men were talking amongst themselves. A pair of guards stepped forward, spears at the ready, then relaxed and waved Henk and William through. Henk took two strides and knelt, pulling William down beside him. “Sire.”

William darted an upward glance through his fringe, uncertain which of the men Henk was addressing, for none of them wore a crown or resembled his notion of what a king should look like. One lord was holding a fine spear though, with a silk banner rippling from the haft.

“So this is the boy whose only value to his father has been the buying of time,” said the man standing beside the spear-bearer. He had greying fair hair and lined, care-worn features. “Rise, child. What’s your name?”

“William, sir.” His dream self stood up. “Are you the King?”

The man blinked and looked taken aback. Then his faded blue eyes narrowed and his lips compressed. “Indeed I am, although your father seems not to think so.” One of his companions leaned to mutter in his ear. The King listened and vigorously shook his head. “No,” he said.

A breeze lifted the silk banner on the lance and it fluttered outwards, making the embroidered red lion at its centre appear to stretch and prowl. The sight diverted William. “Can I hold it?” he asked eagerly.

The lord frowned at him. “You’re a trifle young to be a standard-bearer, hmm?” he said, but there was a reluctant twinkle in his eye and after a moment he handed the spear to William. “Careful now.”

The haft was warm from the lord’s hand as William closed his own small fist around it. Wafting the banner, he watched the lion snarl in the wind and laughed with delight.

The King had drawn away from his adviser and was making denying motions with the palm of his hand.

“Sire, if you relent, you will court naught but John Marshal’s contempt…” the courtier insisted.

“Christ on the Cross, I will court the torture of my soul if I hang an innocent for the crimes of his sire. Look at him…look!” The King jabbed a forefinger in William’s direction. “Not for all the gold in Christendom will I see a little lad like that dance on a gibbet. His hellspawn father, yes, but not him.”

Oblivious of the danger in which he stood, aware only of being the centre of attention, William twirled the spear.

“Come, child.” The King beckoned to him. “You will stay in my tent until I decide what is to be done with you.”

William was only a little disappointed when he had to return the spear to its owner who turned out to be the Earl of Arundel. After all, there was a magnificent striped tent to explore and the prospect of yet more weapons to look at and perhaps even touch if he was allowed—royal ones at that. With such a prospect in mind, he skipped along happily at King Stephen’s side.

Two knights in full mail guarded the tent and various squires and attendants waited on the King’s will. The flaps were hooked back to reveal a floor strewn with freshly scythed meadow and the heady scent of cut grass was intensified by the enclosing canvas. Beside a large bed with embroidered bolsters and covers of silk and fur stood an ornate coffer like the one in his parents’ chamber at Ludgershall. There was also room for a bench and a table holding a silver flagon and cups. The King’s hauberk gleamed on a stand of crossed ash poles, with the helmet secured at the top and his shield and scabbard propped against the foot. William eyed the equipment with longing.

The King smiled at him. “Do you want to be a knight, William?”

William nodded vigorously, eyes glowing.

“And loyal to your king?”

Again William nodded but this time because instinct told him it was the required response.

“I wonder.” Sighing heavily, the King directed a squire to pour the blood-red wine from flagon to cup. “Boy,” he said. “Boy, look at me.”

William raised his head. The intensity of the King’s stare frightened him a little.

“I want you to remember this day,” King Stephen said slowly and deliberately. “I want you to know that whatever your father has done to me, I am giving you the chance to grow up and redress the balance. Know this: a king values loyalty above all else.” He sipped from the cup and then pressed it into William’s small hands. “Drink and promise you will remember.”

William obliged, although the taste stung the back of his throat.

“Promise me,” the King repeated as he repossessed the cup.

“I promise,” William said, and as the wine flamed in his belly, the dream left him and he woke with a gasp to the crowing of roosters and the first stirring of movement amongst the occupants of Drincourt’s great hall. For a moment he lay blinking, acclimatising himself to his present surroundings. It was a long time since his dreams had peeled back the years and returned him to the summer he had spent as King Stephen’s hostage during the battle for Newbury. He seldom recalled that part of his life with his waking memory, but occasionally, without rhyme or reason, his dreams would return him to that time and the young man just turning twenty would again become a fair-haired little boy of five years old.

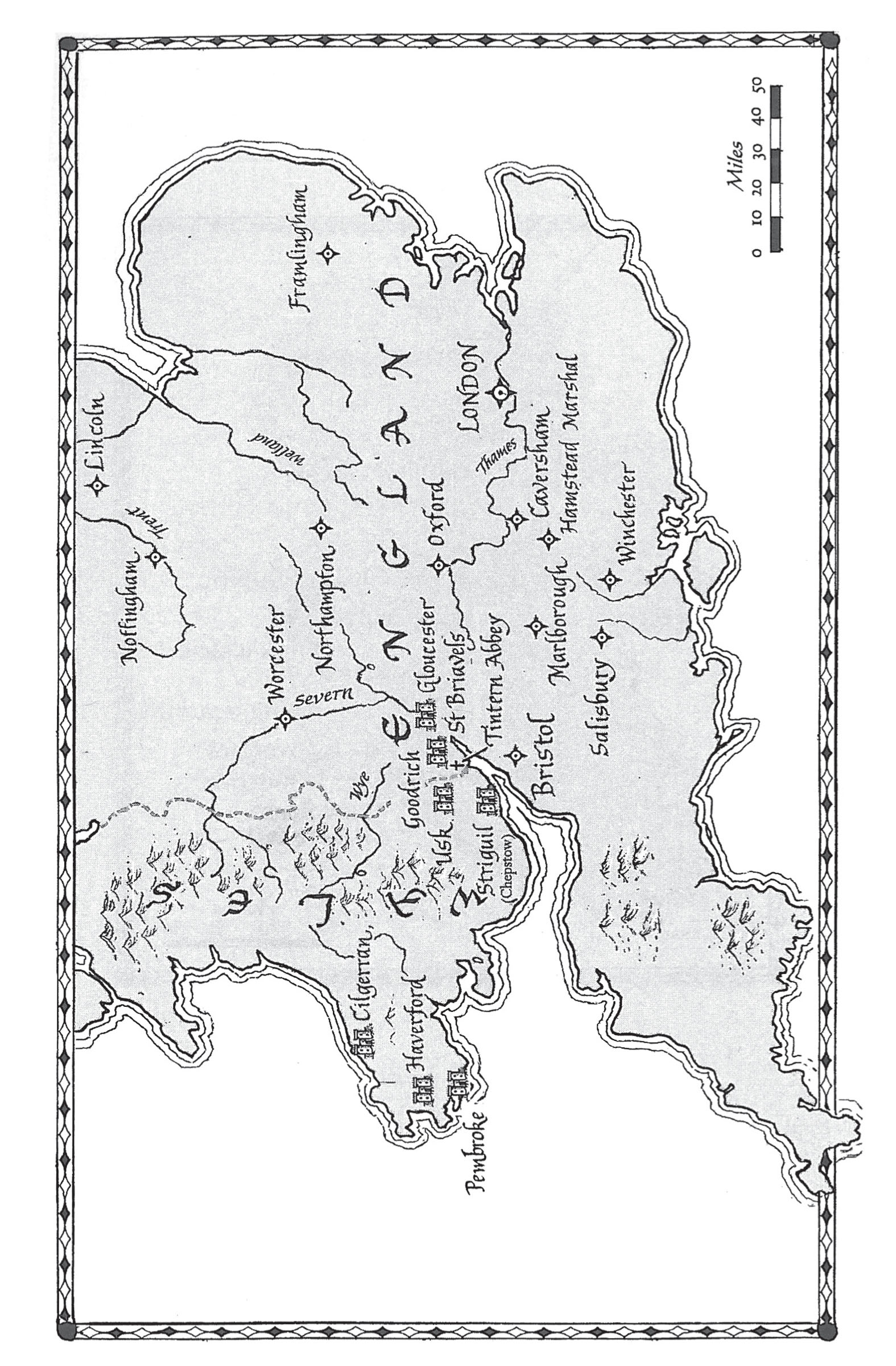

His father, despite all his manoeuvring, machinations, and willingness to sacrifice his fourth-born son, had lost Newbury, and eventually his lordship of Marlborough, but if he had lost the battle, he had rallied on the successful turn of the tide. Stephen’s bloodline lay in the grave and Empress Matilda’s son, Henry, the second of that name, had been sitting firmly on the throne for thirteen years.

“And I am a knight,” William murmured, his lips curving with grim humour. The leap in status was recent. A few weeks ago he had still been a squire, polishing armour, running errands, learning his trade at the hands of Sir Guillaume de Tancarville, Chamberlain of Normandy and distant kin to his mother. William’s knighting announced his arrival into manhood and advanced him a single rung upon a very slippery ladder. His position in the Tancarville household was precarious. There were only so many places in Lord Guillaume’s retinue for newly belted knights with ambitions far greater than their experience or proven capability.

William had considered seeking house room under his brother’s rule at Hamstead, but that was a last resort, nor did he have sufficient funds to pay his passage home across the Narrow Sea. Besides, with the strife between Normandy and France at white heat, there were numerous opportunities to gain the necessary experience. Even now, somewhere along the border, the French army was preparing to slip into Normandy and wreak havoc. Since Drincourt protected the northern approaches to the city of Rouen, there was a pressing need for armed defenders.

As the dream images faded, William slipped back into a light doze and the tension left his body. The blond hair of his infancy had steadily darkened through boyhood and was now a deep hazel-brown, but fine summer weather still streaked it with gold. Folk who had known his father said that William was the image of John Marshal in the days before the molten lead from the burning roof of Wherwell Abbey had ruined his comeliness; that they had the same eyes, the irises deep grey, with the changeable muted tones of a winter river.

“God’s bones, I warrant you could sleep through the trumpets of Doomsday, William. Get up, you lazy wastrel!” The voice was accompanied by a sharp dig in William’s ribs. With a grunt of pain, the young man opened his eyes on Gadefer de Lorys, one of Tancarville’s senior knights.

“I’m awake.” Rubbing his side, William sat up. “Isn’t a man allowed to gather his thoughts before he rises?”

“Hah, you’d be gathering them until sunset if you were allowed. I’ve never known such a slugabed. If you weren’t my lord’s kin, you’d have been slung out on your arse long since!”

The best way to deal with Gadefer, who was always grouchy in the mornings, was to agree with him and get out of his way. William was well aware of the resentment simmering among some of the other knights who viewed him as a threat to their own positions in the mesnie. His kinship to the chamberlain was as much a handicap as it was an advantage. “You’re right,” he replied with a self-deprecating smile. “I’ll throw myself out forthwith and go and exercise my stallion.”

Gadefer stumped off, muttering under his breath. Concealing a grimace, William rolled up his pallet, folded his blanket, and wandered outside. The air held the dusty scent of midsummer, although the cool green nip of the dawn clung in the shadows of the walls, evaporating as the stones drank the rising sunlight. He glanced towards the stables, hesitated, then changed his mind and followed his rumbling stomach to the kitchens.