The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (4 page)

Read The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism Online

Authors: Edward Baptist

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Social History, #Social Science, #Slavery

Understanding something of what it felt like to suffer, and what it

cost to endure that suffering, is crucial to understanding the course of US history. For what enslaved people made together—new ties to each other, new ways of understanding their world—had the potential to help them survive in mind and body. And ultimately, their spirit and their speaking would enable them to call new allies into being in the form of an abolitionist movement that helped to destabilize

the mighty enslavers who held millions captive. But the road on which enslaved people were being driven was long. It led through the hell described by “Seed” (

Chapter 7

), which tells of the horrific near-decade from 1829 to 1837. In these years entrepreneurs ran wild on slavery’s frontier. Their acts created the political and economic dynamics that carried enslavers to their greatest height of

power. Facing challenges from other white men who wanted to assert their masculine equality through political democracy, clever entrepreneurs found ways to leverage not just that desire, but other

desires as well. With the creation of innovative financial tools, more and more of the Western world was able to invest directly in slavery’s expansion. Such creativity multiplied the incredible productivity

and profitability of enslaved people’s labor and allowed enslavers to turn bodies into commodities with which they changed the financial history of the Western world.

Enslavers, along with common white voters, investors, and the enslaved, made the 1830s the hinge of US history. On one side lay the world of the industrial revolution and the initial innovations that launched the modern world. On

the other lay modern America. For in 1837, enslavers’ exuberant success led to a massive economic crash. This self-inflicted devastation, covered in

Chapter 8

, “Blood,” posed new challenges to slaveholders’ power, led to human destruction for the enslaved, and created confusion and discord in white families. When southern political actors tried to use war with Mexico to restart their expansion,

they encountered new opposition on the part of increasingly assertive northerners. As

Chapter 9

, “Backs,” explains, by the 1840s the North had built a complex, industrialized economy on the backs of enslaved people and their highly profitable cotton labor. Yet, although all northern whites had benefited from the deepened exploitation of enslaved people, many northern whites were now willing to

use politics to oppose further expansions of slavery. The words that the survivors of slavery’s expansion had carried out from the belly of the nation’s hungriest beast had, in fact, become important tools for galvanizing that opposition.

Of course, in return for the benefits they received from slavery’s expansion, plenty of northerners were still willing to enable enslavers’ disproportionate

power. With the help of such allies, as “Arms” (

Chapter 10

) details, slavery continued to expand in the decade after the Compromise of 1850. For now, however, it had to do so within potentially closed borders. That is why southern whites now launched an aggressive campaign of advocacy, insisting on policies and constitutional interpretations that would commit the entire United States to the further

geographic expansion of slavery. The entire country would become slavery’s next frontier. And as they pressed, they generated greater resistance, pushed too hard, and tried to make their allies submit—like slaves, the allies complained. And that is how, at last, whites came to take up arms against each other.

Yet even as southern whites seceded, claiming that they would set up an independent

nation, shelling Fort Sumter, and provoking the Union’s president, Abraham Lincoln, to call out 100,000 militia, many white Americans wanted to keep the stakes of this dispute as limited as possible. A majority of northern Unionists opposed emancipation. Perhaps white Americans’ battles

with each other were, on one level, not driven by a contest over ideals, but over the best way to keep the stream

of cotton and financial revenues flowing: keep slavery within its current borders, or allow it to consume still more geographic frontiers. But the growing roar of cannon promised others a chance to force a more dramatic decision: slavery forever, or nevermore. So it was that as Frank Baker, Townshend, and Sheppard Mallory crept across the dark James River waters that had washed so many hulls

bearing human bodies, the future stood poised, uncertain between alternative paths. Yet those three men carried something powerful: the same half of the story that Lorenzo Ivy could tell. All they had learned from it would help to push the future onto a path that led to freedom. Their story can do so for us as well. To hear it, we must stand as Lorenzo Ivy had stood as a boy in Danville—watching

the chained lines going over the hills, or as Frank Baker and others had stood, watching the ships going down the James from the Richmond docks, bound for the Mississippi. Then turn and go with the marching feet, and listen for the breath of the half that has never been told.

N

OT LONG AFTER THEY

heard the first clink of iron, the boys and girls in the cornfield would have been able to smell the grownups’ bodies, perhaps even before they saw the double line coming around the bend. Hurrying in locked step, the thirty-odd men came down the dirt road like a giant machine. Each hauled twenty pounds of iron, chains that draped from neck to neck

and wrist to wrist, binding them all together. Ragged strips flapped stiffly from their clothes like dead-air pennants. On the men’s heads, hair stood out in growing dreads or lay in dust-caked mats. As they moved, some looked down like catatonics. Others stared at something a thousand yards ahead. And now, behind the clanking men, followed a marching crowd of women loosely roped, the same vacancy

painted in their expressions, endurance standing out in the rigid strings of muscle that had replaced their calves in the weeks since they left Maryland. Behind them all swayed a white man on a gray walking horse.

The boys and girls stood, holding their hoe handles, forgetful of their task. In 1805, slave coffles were not new along the south road through Rowan County, here in the North Carolina

Piedmont, but they didn’t pass by every day. Perhaps one of the girls close to the road, a twelve-year-old willow, stared at the lone man who, glistening with sweat and fixed of jaw, set the pace at the head of the double file. Perhaps he reminded her of her father, in her memory tall. A few years back, he’d stopped coming to spend his Saturday nights with them. The girl’s mother said he’d been

sold to Georgia. Now in the breath of a moment, this man caught her staring eyes with his own scan as he hurried past. And perhaps, though he never broke stride, something like recognition flashed over a face iron as his locked collar. This man, Charles Ball, a twenty-five-year-old father of two, could not help but see his own

daughter ten years hence, years he knew she’d pass without him. Then

he was gone down the road, pulling the rest of the human millipede past the girl. As the women’s bare soles receded—the white man on the horse following last, looking down, appraising her—the overseer on the far side of the field called out “Hey!” to her stock-still self, and she would surely have realized that the coffle carried her own future with them.

1

There are 1,760 yards in a mile—more

than 2,000 steps. Forty thousand is a long day’s journey. Two hundred thousand is a hard week. For eighty years, from the 1780s until 1865, enslaved migrants walked for miles, days, and weeks. Driven south and west over flatlands and mountains, step after step they went farther from home. Stumbling with fatigue, staggering with whiskey, even sometimes stepping high on bright spring mornings when

they refused to think of what weighed them down, many covered over 700 miles before stepping off the road their footsteps made. Seven hundred miles is a million and a half steps. After weeks of wading rivers, crossing state lines, and climbing mountain roads, and even boarding boats and ships and then disembarking, they had moved their bodies across the frontier between the old slavery and the new.

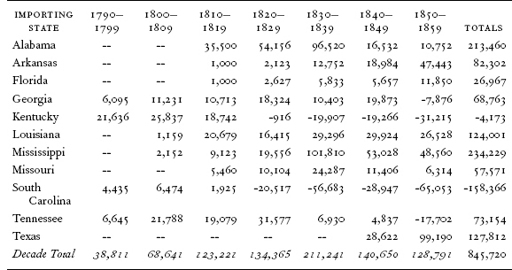

Over the course of eighty years, almost 1 million people were herded down the road into the new slavery (see

Table 1.1

). This chapter is about how these forced marchers began, as they walked those roads, to change things about the eastern and western United States, like shifting grains moved from one side of a balance to another. It shows how the first forced migrations began to tramp down paths

along which another 1 million walkers’ 1.5 trillion steps would shape seven decades of slavery’s expansion in the new United States. And it shows how the paths they made on the land, in politics, and in the economy—the footprints that driven slaves and those who drove them left on the fundamental documents and bargains of the nation—kept the nation united and growing.

For at the end of the American

Revolution, the victorious leaders of the newly independent nation were not sure that they could hold their precarious coalition of states together. The United States claimed vast territories west of the Appalachian Mountains, but those lands were a source of vulnerability. Other nations claimed them. Native Americans refused to vacate them. Western settlers contemplated breaking loose to form

their own coalitions. East of the Appalachians, internal divisions threatened to tear apart the new country. The American Revolution had been financed by printing paper money and bonds. But that had produced inflation, indebtedness, and low commodity prices, which now, in the 1780s, were generating a massive economic crisis.

There was no stable currency. The federal government—such as it was—had

no ability to tax, and so it also could not act as a national state.

TABLE 1.1. NET INTERNAL FORCED MIGRATION BY DECADE

Source:

Michael Tadman,

Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South

(Madison, 1989), 12. Some states not included.

Between the arrival of the first Africans in 1619 and the outbreak of Revolution in 1775, slavery had been one of the engines of colonial economic growth. The number of Africans brought to Maryland and Virginia before the late 1660s was a trickle—a few

dozen per year. But along with white indentured servants, these enslaved Africans built a massive tobacco production complex along the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Over those formative fifty years, settlers imported concepts of racialized slavery from other colonies (such as those in the Caribbean, where enslaved Africans already outnumbered other inhabitants by the mid-seventeenth century).

By 1670, custom and law insisted that children were slaves if their mothers were slaves, that enslaved Africans were to be treated as rights-less, perpetual outsiders (even if they converted to Christianity), that they could be whipped to labor, and that they could be sold and moved. They were chattel property. And everyone of visible African descent was assumed to be a slave.

2

After 1670 or

so, the number of enslaved Africans brought to North America surged. By 1775, slave ships had carried 160,000 Africans to the Chesapeake colonies, 140,000 to new slave colonies that opened up in the Carolinas and Georgia, and 30,000 to the northern colonies. These numbers were small compared to the myriads being carried to sugar colonies,

however. Slave ships landed more than 1.5 million African

captives on British Caribbean islands (primarily Jamaica and Barbados) by the late 1700s and had brought more than 2 million to Brazil. In North America, however, the numbers of the enslaved grew, except in the most malarial lowlands of the Carolina rice country. By 1775, 500,000 of the thirteen colonies’ 2.5 million inhabitants were slaves, about the same as the number of slaves then alive in

the British Caribbean colonies. Slave labor was crucial to the North American colonies. Tobacco shipments from the Chesapeake funded everyone’s trade circuits. Low-country Carolina planters were the richest elites in the revolutionary republic. The commercial sectors of the northern colonies depended heavily on carrying plantation products to Europe, while New England slave traders were responsible

for 130,000 of the human beings shipped in the Middle Passage before 1800.

3