The Hare with Amber Eyes (29 page)

Read The Hare with Amber Eyes Online

Authors: Edmund de Waal

Jiro was twenty-six, slight and handsome, fluent in English and a lover of Fats Waller and Brahms. When they met he had just returned from three years studying at an American university on a scholarship. His passport from the Administration Office Occupation Forces was stamped no. 19. Jiro remembered his anxiety about how he would be treated in America, and how the newspapers wrote it up: ‘a young Japanese boy off to America in a grey flannel suit and white Oxford shirt’.

Jiro had grown up as the middle child of five siblings in a merchant family that made lacquered wooden clogs in Shizuoka, the city between Tokyo and Yokohama: ‘our family made the very best, painted

geta

with

urushi

lacquer on them. My grandfather Tokujiro made our fortune out of

geta

…We had a large traditional house with ten people working in the shop, and they all had quarters to live in.’ They were a prosperous and entrepreneurial family, and in 1944 Jiro, aged eighteen, had been sent to the preparatory school for Waseda University in Tokyo and then on to the university itself. Too young to fight, he had seen Tokyo obliterated around him.

Jiro, my Japanese uncle, has been part of my life for as long as Iggie. We sat together in the study of his Tokyo apartment and he talked of those early days together. They would leave the city on Friday nights and ‘have our weekends around Tokyo, in Hakone, Ise, Kyoto, Nikko, or stay in

ryokan

and

onsen

and have good food. He had a yellow DeSoto convertible with a black top. The first thing after leaving our luggage at the

ryokan

Leo always wanted to do, was to go to antique shops – Chinese pots, Japanese pots, furniture…’ And during the week they would meet up after work. ‘He’d say “Meet me at the Shiseido restaurant for beef curry rice, or for crabmeat croquette.” Or we’d meet at the bar of the Imperial. There were so many parties at home. We’d have whisky together late at night after everyone had gone, with opera on the gramophone.’

Their life was Kodachrome – I can see that yellow-and-black car glistening like a hornet on a dusty road in the Japanese alps, the pinkness of the croquette framed on white.

They explored Japan together, travelling to an inn that specialised in river trout one weekend; to a town on the coast for an autumn

matsuri

, a jostling parade of red-and-gold festival floats. They went to exhibitions of Japanese art at the museums in Ueno Park. And to the first travelling exhibitions of Impressionism from European museums, where the queues stretched from the entrance to the gates. They came out from seeing Pissarro, and Tokyo looked like Paris in the rain.

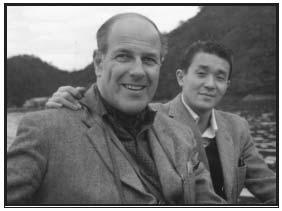

Iggie and Jiro on a boat in the Inland Sea, Japan, 1954

But music was closest to the heart of their life together. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony had become extremely popular during the war. The Ninth –

Daiku

as it was known colloquially – became an entrenched part of New Year, with huge choirs singing the ‘Ode to Joy’. Under the Occupation, the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra had been partly sponsored by the authorities with programmes selected from requests by the troops. And now, in the early 1950s, there were regional orchestras across Japan. Schoolchildren with satchels on their backs clutched violin cases. Foreign orchestras started to visit, and Jiro and Iggie would go to one concert after another: Rossini, Wagner and Brahms. They saw

Rigoletto

together, and Iggie recalled that it was the first opera he had seen with his mother in their box in Vienna during the First World War, and that she had cried at the final curtain.

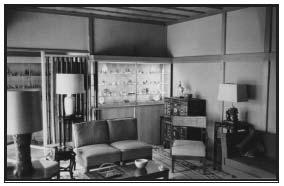

And so this is the fourth resting-place of the netsuke. It is a vitrine in a sitting-room in post-war Tokyo looking out across a bed of clipped camellias, where the netsuke are washed late at night by waves of Gounod’s

Faust

, played loud.

The arrival of the Americans meant that Japan had, once again, become a country to plunder, a country full of attractive objects, pairs of Satsuma vases, kimono robes, lacquer and gilt swords, folding screens with peonies, chests with bronze handles. Japanese stuff was so cheap, so abundant.

Newsweek

’s first report on Occupied Japan on 24th September 1945 was headlined ‘Yanks Start Kimono Hunt, Learn What Geishas Doesn’t’ (

sic

). That blunt and cryptic headline, joining souvenirs and girls, sums up the Occupation. The

New York Times

later that year reported ‘A Sailor Goes on a Shopping Spree’: if you were a GI there was very little else to buy, after you had spent what you could on cigarettes, beer and girls.

A successful

après-guerre

opened a small money-exchange booth on the pier at Yokohama, converting dollars into yen for the first American soldiers. He also bought and resold American cigarettes. But, crucially, the third part of his business was selling ‘cheap Japanese bric-a-brac, such as bronze Buddha images. Brass candleholders, and incense burners, which he had salvaged from bombed-out areas. Being great novelties in those days, these curio items sold like proverbial hotcakes.’

How did you know what to buy? All soldiers ‘had to suffer an hour in combat subjects [such] as Japanese flower arrangement, incense burning, marriage, dress, tea ceremonies, and fishing with cormorants,’ John LaCerda acidly commented in

The Conqueror Comes to Tea: Japan under MacArthur

, published in 1946. For the more serious there were the new guides to Japanese arts and craft, printed on grey paper so thin that it feels like tissue. The Japan Travel Bureau published its guides ‘to give to the passing tourists and other foreigners interested in Japan a basic knowledge of various phases of Japanese culture’. They included, amongst other subjects:

Floral Art of Japan

,

Hiroshige

,

Kimono (Japanese Dress)

,

Tea Cult of Japan

,

Bonsai (Miniature Potted Trees).

And, of course,

Netsuke: A Miniature Art of Japan.

From the bric-a-brac salesmen on the pier at Yokohama to the men with a handful of lacquers on a white cloth sitting outside a temple, it was difficult not to encounter Japan for sale. Everything was old, or labelled as old. You could buy an ashtray, a lighter or tea towel with images of geisha, Mount Fuji, wisteria. Japan was a series of snapshots, of postcards coloured like brocade, cherry blossom as pink as candy-floss. Madame Butterfly and Pinkerton, cliché jumbled up against cliché. But you could just as easily buy an ‘exotic remnant of the Age of the Daimyos’. As

Time

put it in the article ‘Yen for Art’, writing about the Hauge brothers, who had amassed an exceptional collection of Japanese art:

Of the countless GIs who spent a tour of duty in Japan, few failed to load up on souvenirs. But only a handful of Americans realised what a collector’s paradise was within their reach…The Hauges got off to a flying start with the whirlwind of inflation that swept the Japanese yen from 15 all the way to 360 to the dollar. At the same time the Hauges were reaping a paper harvest of yen, Japanese families, hit with postwar taxes, were living an ‘onionskin’ existence, peeling off long-treasured art works to stay afloat.

Onionskin, bamboo shoots. They were images of vulnerability, tenderness and tears. They were also images of undressing. It paralleled the stories so avidly told and retold by Philippe Sichel and the Goncourts in Paris during the first febrile rush of

japonisme

of how you could buy anything, how you could buy anyone.

Iggie might be expatriate, but he was still an Ephrussi. He too started to collect. On his trips with Jiro he bought Chinese ceramics – a pair of Tang Dynasty horses with arching backs, celadon-green dishes with swimming fish, fifteenth-century blue-and-white porcelain. He bought Japanese golden screens with crimson peonies, scrolls with misty landscapes, early Buddhist sculpture. You could buy a Ming Dynasty bowl for a carton of Lucky Strikes, Iggie told me, guiltily. He showed it to me. It has a perfect high ring, if you tap it gently. It has peonies painted in blue under a milky glaze. I wonder who had to sell it.

It was during these years of the Occupation that netsuke became ‘collectables’. The Japan Travel Bureau guide on netsuke, published in 1951, records ‘valuable help given by Rear Admiral Benton W. Dekker, former commander of the US Fleet Activities at Yokosuka, Japan and a most devoted connoisseur of Netsuke’. This guide, in print for thirty years, gave its view of netsuke in the clearest way:

The Japanese are by nature clever with their fingers. This deftness may be attributed to their inclination to small things, developed in them because they live in a small insular country, and are not continental in character. Their habit of eating their meals with chopsticks, which they learn to handle cleverly from early childhood, may also be regarded as one of the causes that made them thus deft-handed. Such a special characteristic is responsible at once for the merits and demerits of Japanese art. The people lack an aptitude for producing anything on a large scale or deep and substantial. But they display their nature in finishing their work with delicate skill and scrupulous execution.

The way that Japanese objects were talked of had not changed in the eighty years since Charles bought them in Paris. Netsuke were still to be enjoyed for all those positive attributes given to precocious children, the ability to finish, scrupulousness.

It is a bitter thing to be compared to a child. It was made even more painful when this was publicly expressed by General MacArthur. Sacked by President Truman on the grounds of insubordination over the Korean War, the General left Tokyo for Haneda airport on 16th April 1951: ‘escorted by a cavalcade of military police motorcyclists…Lining the route there were American troops, the Japanese police and Japanese people. School children were given time off from classes to line the road; public servants in post offices, hospitals or administrations were given the opportunity to attend also. The Tokyo police estimated that 230,000 persons had witnessed MacArthur’s departure. It was a quiet crowd,’ wrote the

New York Times

, ‘which gave little outward sign of emotion…’ At the Senate hearings on his return, MacArthur compared the Japanese to a twelve-year-old boy in comparison to a forty-five-year-old Anglo-Saxon adult: ‘You can plant basic concepts there. They [are] close enough to origin to be elastic and acceptable to new concepts.’

It felt like public, global humiliation for a country free after seven years of occupation. Since the war Japan had been substantially rebuilt, partly through American subsidies, but substantially by their own entrepreneurial skills. Sony, for instance, started as a radio repair shop in a bombed-out department store in Nihonbashi in 1945. It created one new product after another – electrically heated cushions in 1946, Japan’s first tape recorder the following year – by hiring young scientists and buying materials on the black market.

If you walked along the Ginza, the central shopping boulevard in Tokyo, in the summer of 1951 you would pass one well-stocked store after another: Japan was making its way in the modern world. You would also pass Takumi, a long thin shop with dark bowls and cups stacked on shelves alongside bolts of indigo cloth from folk-craft weavers. In 1950 the Japanese government introduced the category of the National Living Treasure, someone – usually an elderly man – whose skill in lacquer or dying or pottery was rewarded with a pension and fame.

Taste had swung round towards the gestural, intuitive, ineffable. Anything made in a remote village became ‘traditional’ and was marketed as intrinsically Japanese. These years saw the start of Japanese tourism, with booklets published by the Japanese Department of Railways:

Some Suggestions for Souvenir Seekers

. ‘Travel of any kind would not be complete without some souvenirs to take home.’ You should return with the right

o-miyage

, or gift. It could be a sweet-meat, a kind of biscuit or dumpling specific to one village, a box of tea, a pickled fish. Or it could be a handicraft, a sheaf of paper, a tea-bowl from a village kiln, an embroidery. But it must have its regional specificity pulsing behind its paper-and-cord wrapping, its calligraphic tag: there is a mapping of Japan, a geography of appropriate gifts. Not to bring an

o-miyage

is an affront in some way to the idea of travelling itself.

Netsuke now belonged to the age of the Meiji and the opening up of Japan. In the hierarchies of knowledge, netsuke were now rather looked down on as

over-skilled

: they carried the slightly stale air of

japonisme

with them, of the marketing of Japan to the West. They were just too deft.

No matter how many calligraphies were shown – a single explosive brushstroke of black by some monk, a concentration of decades into four seconds of control – show something small and ivory, ‘a group of Kiyohimi and a dragon circling the temple bell within which the monk Anchin hides’ and everyone marvelled. Not at the idea, or the composition, but at the possibility of concentrating for so long on such a small thing. How did Tanaka Minko carve the monk inside the bell through that tiny, tiny hole? Netsuke were too popular with Americans.

Iggie wrote about his netsuke in an article published in Japanese in the

Nihon Keizai Shimbun

, the Tokyo equivalent of the

Wall Street Journal

. He described his memories of them as a child in Vienna and their escape from the Palais, under the noses of the Nazis in the pocket of a maid. And he wrote of them returning to Japan. Good fortune had brought them back to Japan after three generations in Europe. He had, he said, asked Mr Yuzuru Okada of the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno, the writer on netsuke, to come and examine the collection. Poor Mr Okada, I think, trailing out to a

gaijin

’s house to smile over another collection of Westerner’s bric-a-brac evening after evening. ‘He met me very reluctantly – I did not know why – and he glanced at about three hundred netsuke spread out on a table as if he were sick of seeing them…Mr Okada picked up one of my netsuke. Then he began to carefully examine the second one with his magnifier. At last, after he had examined the third one for a long time, he suddenly stood up and asked me where I got them…’

The vitrine of netsuke in Iggie’s house in Azabu, Tokyo, 1961

These were great examples of Japanese art. They might be currently out of fashion – in Okada’s museum in Ueno Park in Tokyo’s National Museum of Japanese art, a visitor would find only a single vitrine of netsuke amongst the chilly halls of ink-paintings – but here was real sculpture for the hand.

Ninety years after they first left Yokohama, someone picks up a netsuke and knows who made it.