The haunted hound; (10 page)

Read The haunted hound; Online

Authors: 1909-1990 Robb White

His father \\as eating breakfast.

"Morning, Dad/' Jonathan said, sitting down.

His father put the newspaper away. "Good morning. How does it feel to be a mathematical genius?''

Jonathan just laughed.

"I've been thinking," his father said. "That hundred deserves something pretty special, Jon. Think awhile and tell me what you'd like to have more than anything else."

"I don't have to think. All I want is a dog."

His father didn't look up. "A dog, son? Well, in the first place you couldn't keep one here in the apartment. And in the second no dog is going to be happy in a city."

Jonathan said quietly, "If we lived at the Farm I could

have a dog. And we wouldn't have to pay rent for this place. And we could plant crops and make some money on the Farm."

''Mrs. Johnson wouldn't live out there, son. Who'd take care of you when I was away?"

''Her!" Jonathan said. ''I don't need her to take care of me any more. So you wouldn't have to pay her salary. But Mamie would go back. Then, with a new car, it wouldn't take you long to drive back and forth." He stopped to get his breath, then went on, talking as fast as he could. ''And if anybody had to take care of me, Mrs. Worth could, couldn't she? And I could ride horseback to school with Judy. And have a dog." He paused again and then asked, "Couldn't we just go back out there for a little while, Dad? Just for a little while?"

His father had the lawyer look again and the cold, polite voice. "That's out of the question, son."

Jonathan didn't say anything else until he was almost through eating breakfast. At last, though, he told his father about catching the bass. "And Judy really was surprised," he added. "At first she didn't think the spinning rod was any good. But after that fish she changed her mind. You don't mind if I give it to her, do you, because I did."

"Certainly not," his father said.

"I won't ever need it again," Jonathan said.

"Oh, there are other places to fish, Jon." 1 guess so.

His father got up then and left for his office. Jonathan,

feeling strangely sad and defeated, wandered into the kitchen.

As soon as the door closed Mamie looked at him sternly.

''I heard every word you said," she told him, still stern.

''One of these days when you're listening at the door, somebody's going to open it and bop you/' he warned her.

''Ain't bopped me yet and ain't gonna. Listen, now, Jonathan, don't talk to your dad about going out to the Farm to live. It hurts him something awful."

"How?"

"You're too young to know. But he was a man who truly loved his wife, and when she died—oh, she was a beautiful woman—it like to have broke his heart. If he lived out there, he'd just naturally have to think about her all the time, and that would break his heart. It was out there that he saw her well and happy for the last time. Now he's coming along real good; he's getting over his sorrow. He ain't working so hard night and day to keep from thinking about her. So, maybe, after a while, we can go back. But not now, Jonathan. Not now."

"I guess not," Jonathan said, feeling sadder than ever.

"And don't you go out there no more. Your dad shouldn't even be made to think about the Farm. So don't you go out there and come back talking about it."

"Suppose he doesn't even know about it? Suppose I just go and not let him find out?" Jonathan asked.

"That'd be all right, long as you're mighty careful not to let him know." Mamie sat down. "Oh, but I'd love to go

back out there. I can't cook in this httle old kitchen with everything shining at me all the time. And this place is too high up off the ground. Me, I like to walk right out the back door and there's the ground to put my feet on.''

With no school Jonathan just wasted the whole morning doing nothing. He found the superintendent of the building, who pointed out to him what would happen if they let dogs into the apartment. ''Suppose all three hundred apartments had a dog, Jonathan? And all those three hundred dogs had puppies? That'd make about a thousand dogs. Then next year those thousand dogs would have puppies; that'd make five thousand dogs maybe. Man, there'd be so many dogs in here the people couldn't get in. And the racket and the dog fights. No, sir, we just can't let in the first dog."

When Jonathan got hungry, he wandered back to the apartment. Mamie told him that there was a letter for him.

He was surprised, and looked to see who it was from before he read it. It was signed, 'Tours truly, Judith Worth Shelley."

Dear Jonathan:

I hope you passed your examination all right. If you did not, I will feel sorry.

I like the rod and reel you gave me very much and I have some real reel oil for it and keep it in a closet so nothing like a dog or a horse can knock it down or hurt it.

It is a very nice rod and reel. I cannot make it throw anything anywhere. I tried very hard to make it throw some-

thing somewhere. Then my uncle tried to make it throw and after him my aunt, but it will not throw. So I am writing you this letter to find out how to make it. I would be obliged if you would \\Tite me a letter saying how it is supposed to throw. Write it real clear so I will know what it says and how to do it.

The best way is for you to come back someday and show me how to make it throw.

Yours truly,

Judith Worth Shelley

P.S. That dog Pot Likker went away the night you went away and he has not come back yet. It makes me sad but not as sad as I would be if it had been one of the other dogs. My uncle says he thinks a rattlesnake got him.

It made Jonathan sad, too, and he thought about the dog as he ate lunch. Then he went into his father's den and started to wTite Judy a letter. At first it was easy to tell her how^ to take the rod with her right hand, the reel hanging down underneath, and then take the line with your finger. But when he got to the part about what to do next he got all mixed up and couldn't remember very well himself.

He was still struggling with the letter w^hen Mrs. Johnson walked in. 'Tackage for you/' she said, handing him a long oblong package.

'Thanks, Mrs. Johnson."

*'What's in it?" she asked, standing in the door.

*'I don't know," Jonathan said. 'Til open it after a while. I'm writing a letter now."

'Who to?'' she asked.

''Somebody/'

"Well, naturally. But who?"

He knew that she would keep pestering him until he told her, so he did, and she finally left the room.

After a few more minutes he gave up trying to explain to Judy in writing. He opened the package and then stood there looking at what was in it and loving his father. This was a time when he could just love him and not even try to understand the way he acted sometimes, or the way he thought.

His father had bought him a bamboo spinning rod and a reel exactly like the one he had given Judy. There were also some spinning lures and braided nylon line. The whole thing fitted into an aluminum case. There was a note in the package, too. Jonathan opened it and a ten-dollar bill fell out. On a little card his father had written: ''It's been so long since I've had a chance to go fishing, I've forgotten what they'll bite, so use the enclosed if the ones I picked won't catch 'em. Good luck, Yr. Dad."

Jonathan went straight over to the phone and called the bus line. There was a bus leaving for Millersville in twenty minutes.

Jonathan got out of the bus and walked through the woods to the Farm. He had brought his new fishing gear and he went directly to Mr. Worth's house.

There were dogs on the porch, dogs under the house,

dogs coming from everywhere. And all of them barking at him. Jonathan stopped in the yard, waiting for somebody to come out of the house. But when no one did and the dogs kept on barking, Jonathan took a deep breath and suddenly yelled as loud as he could, ''Hey, you/"

The dogs stopped barking, all together, and at the same instant, and sat staring at him.

Jonathan laughed out loud. He must have sounded like his father when he hollered at them at night.

Old Mister Blue came slowly over and put his front paws on Jonathan's chest. Jonathan rubbed behind his ears and finalh' pushed him down again.

Pot Likker was missing.

Jonathan went up on the porch and knocked, but no one answered. The house wasn't shut up, so he decided Judy must be down around the stables somewhere.

With some of the dogs going along with him, he went down to the stables. When he called, not too loud, for Judy, the horses came and stuck their heads out of the stalls. There were four of them and one colt, who stuck her head out, too.

Judy wasn't anywhere around. He kept hollering for her, but nobody answered.

Maybe, he thought, she was fishing—or trying to.

Jonathan decided to take a short cut across the stable pasture to the Big Pond. With his rod and reel still in the case, he climbed a high board fence with barbed wire on top and started down the long pasture.

None of the dogs came with him, but he could hear them playing and arguing as they went back toward the house.

He kept calling for Judy.

The pasture was square. At the far end there were four or five hickory trees for shade, but the rest of it was open and flat.

He wasn't paying much attention as he walked along, clipping off daisies with the end of the light rod case. He wondered ^^'here Judy w^as and then what had become of Pot Likker. It was a pity that something had happened to him. He was a good-looking, big, strong dog and, even though he might have been without anv good instincts, Jonathan just hated to think of any dog getting bit by a rattlesnake and dying out in the woods somewhere.

And he was the last of the long line of hounds going back into Jonathan's great-grandfather's time.

Jonathan had been lucky with rattlesnakes and had never seen one alive. But he remembered in the old days when his father would give a dollar to anyone who brought in a dead one. Jonathan recalled one in particular. WTien the man held it up by the tail it was longer than his father was tall and it was as big around as a man's leg. Jonathan remembered his father saying that a snake that size could knock a man down if it struck him.

Poor Pot Likker, Jonathan thought.

Perhaps it was because he had been thinking about snakes and was jittery; anyway, Jonathan stopped in his

tracks when he saw something move among the hickory trees.

He was about fifty feet from them, having come almost the length of the pasture, and something big and gray moved among the trees.

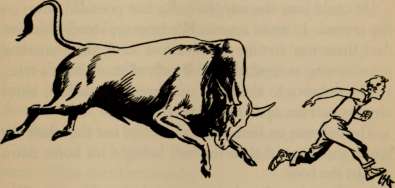

He stood perfectly still, staring. A Brahma bull came out into the clear, moving away from him, but watching him.

The animal was slate gray on the body with dark gray foreshoulders and hump. It was big—the biggest bull he had ever seen.

It stopped walking, turned, and stood without moving, looking straight at Jonathan.

The bull's horns swept out from his head in a long curve. His big floppy ears drooped. Above his head Jonathan could see the Brahma hump, and, below, the dewlap hanging down almost to the ground.

For a long moment neither Jonathan nor the bull moved a muscle. Jonathan could suddenly hear bugs and birds making noises. Faintly, far away, he could hear dogs. But the noises only made everything seem more silent where he was with the bull.

As though he had eyes in the back of his head, Jonathan could see the long way down the pasture he had come. He guessed that it was a good quarter of a mile. And he was in the middle—to the fence on either side of him was another quarter mile.

Suddenly, very clearly, he remembered when he was a

little boy once asking his father if a bull could outrun a man. His father had laughed and said, ''A man wouldn't get started, son. A bull can outrun a horse for a good while.''

Jonathan's flesh began to crawl and prickle all over. His instinct was to start running, running with all the strength he had. But he stood still, trying to think. If he ran, the bull could catch him. He was sure of that.

He couldn't get to the hickory trees; the bull was in the way.

Maybe, Jonathan thought, the best thing to do was to walk away—toward the fence. Walk slowly away. Then the bull wouldn't think he was scared. Maybe the bull wouldn't even notice him, because bulls couldn't see very well anyhow. And maybe this was a tame bull, a gentle bull.

Jonathan remembered that book about a bull named Ferdinand, who wouldn't hurt a fly. Maybe this was a Ferdinand kind of bull.

Jonathan looked at the bull harder, trying to find out what the bull was thinking about.

Although he wasn't moving, he still looked dangerous. He wasn't pawing the ground and snorting the way bulls in the movies do; he wasn't shaking his head or jabbing with his horns. He was standing absolutely still. But he looked terrible.

Jonathan's whole body felt stiff and awkward as he swung slowly and lifted one foot off the ground. He put the foot down gently, feeling the grass give way under it. Then he picked up his other foot.

All the time he kept watching the bull.

He had taken three long, slow steps when the bull's big hairy ears shot straight forward and stayed pointing right at him.

Jonathan, his leg muscles quivering, picked up his foot qgain.

Everything exploded.

The bulFs tail stood straight up, it threw up its head, and