The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy (4 page)

Quite rightly, Barker disassociated himself from both

Underworld

and

Rawhead Rex

. There was no more contact between himself and George Pavlou and Green Man unknowingly let their options lapse on the other four stories from

Books of Blood

. This didn’t stop them trying to develop another couple of projects based on the tales, but Barker involved his lawyers and the producers soon backed down.

Rawhead Rex as depicted by artist Les Edwards was much closer to the original concept than its cinematic counterpart (courtesy Les Edwards).

It is interesting, though, that without these experiences he wouldn’t have had the major impetus to direct. If they had taught him one thing it was this: To see a satisfactory adaptation of his work, he’d have to make one himself. And it is ironic that a line David Dukes utters in

Rawhead

should show him the way. “Go to Hell,” he says. “Just go right to Hell!”

In the same 1986 interview with

Fangoria

, Barker also stated: “I want to direct. I directed in theatre, and I like working with actors, I like community projects. So, we’re putting a project together from a novella I wrote called ‘The Hellbound Heart.’ ... I did a screenplay from it which I hope to be directing this year. We’re going to call the movie

Hellraiser

.”

15

Obviously the author would find film directing a little different from plays, but his theater experiences still stood him in good stead. It is at this point that we must also consider the art house shorts he shot in the 1970s, made with many of those same friends. Actually, Barker’s first films were naive experiments with a friend from his early teens, Phil Rimmer. He’d already written short plays with Rimmer—

Voodoo

&

Inferno

(1967)—about crazed Germans and, naturally, Hell. Then they progressed on to stop-motion efforts with a Super 8 millimeter camera influenced greatly by Barker’s hero, effects man Ray Harryhausen. One of these involved an Action Man (the UK equivalent of a G.I. Joe doll), some plasticine and lots of worms from the garden. The setting was a slime-covered graveyard constructed in Barker’s bedroom and the directors held lamps close enough to make the scenery bubble.

In 1973, the pair made a version of Oscar Wilde’s

Salome

, itself a biblical tale which recounts another bargain. The legend of Salome revolves around King Herod’s stepdaughter, who falls in love with the pious Jokanaan (John the Baptist) but is rejected. In exchange for his severed head, she dances for Herod. The group filmed on 8mm stock in the cellar of a florist’s shop in Liverpool. They had a single handheld light and the sets were wallpaper turned over with patterns painted on it. Anne Taylor took the title role, while Doug Bradley—who had played a blind Jokanaan in a previous stage version—was granted his first cinematic encounter with make-up, playing King Herod. The whole thing was developed in Rimmer’s house, then edited by hand.

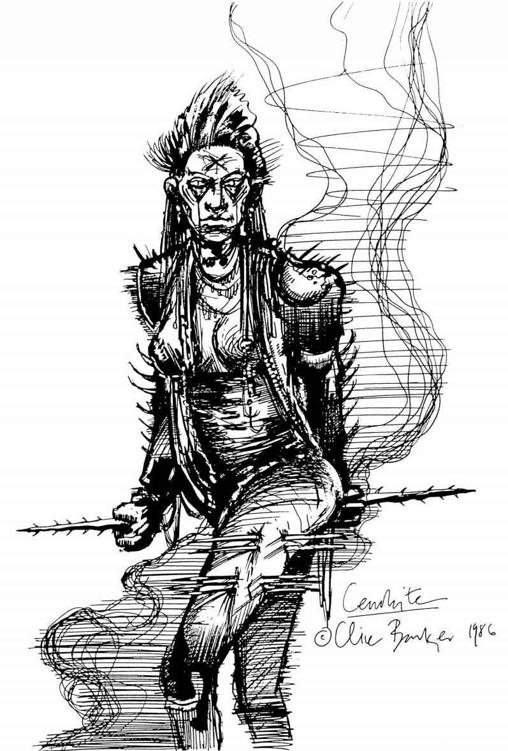

Cenobite concept sketch for

Hellraiser

(courtesy Clive Barker).

Displaying definite expressionist and surrealist tendencies, as one would expect after the group’s exposure to film societies in the area, the movie also boasts some unique visual parallels with

Hellraiser

. We pass through a doorway, for instance, and a strange light sheen gives the frame an unreal quality. Taylor very closely resembles Kirsty with her long, dark hair, white smock and black-stained eyes. Then there are the requisite candles (present in both Kirsty’s dream sequence and at Frank’s puzzle-solving near the beginning). And the resemblance between Herod and the bearded Keeper of the Box is uncanny.

16

But most intriguing is the first cinematic use of a kiss as a betrayal, in addition to Taylor’s scratching of a cheek, which Kirsty recreates when Uncle Frank is pretending to be her father.

Cenobite concept sketch for

Hellraiser

(courtesy Clive Barker).

Yet more similarities abound in a second short,

The Forbidden

(1975–78). This is probably not that surprising, as it was based loosely on Christopher Marlowe’s

Doctor Faustus

, Barker’s preferred reworking of the Faust myth. Funded by £600 from Merseyside Arts, this time the footage was shot in negative on 16mm black and white stock, but stood for quite a while before being put together. The first thing to say is that

The Forbidden

plays very heavily on an obsession with puzzles and games. The opening shots are bare feet on a chessboard floor, while the odd symbols painted on paper and put together like a jigsaw puzzle recall the sides of the Lament Configuration box itself. Hand animated birds flutter behind a grid, trapped like the birds at the pet shop where Kirsty works. And there is a gridded piece of wood with nails at each intersection.

Talking about this, Doug Bradley recalls:

Clive had built what he called his nail board ... and spent endless hours playing with what happened if a light was swung around in front of it to see the way the shadows of the nails moved and what happened if it was top lit and so forth. Of course, when I saw the first illustrations for this gentleman [Pinhead] it rang a bell with me—that here was actually Clive putting the ideas that he’d been playing around with, with the nail board, in

The Forbidden

. Now ten to fifteen years later or whatever, here he’d actually put the image over a human’s face, which is typical of the way he works.

17

But undoubtedly the most recognizable factors are the Angels at the end—robed figures who inflict pain—and the figure of Faust himself once he is skinned. Peter Atkins played him in full make-up, actually strips of paint that were peeled back revealing new layers of flesh and muscle. When viewed in negative and for the amount of money available, the results are shockingly effective and would prove to be Barker’s first ventures into making less look like more. Owing much to those Vesalius pictures, Faust’s character is a distinct antecedent to skinless Frank Cotton in

Hellraiser

, and those torturing him can only be equated to the Cenobites.

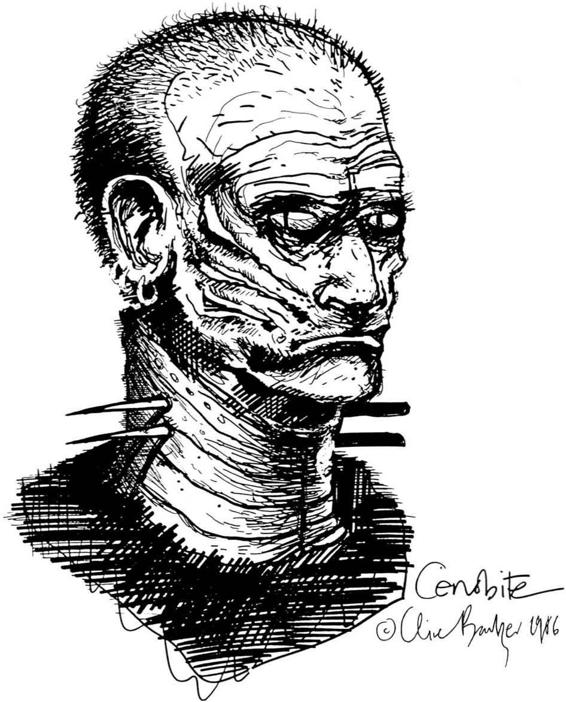

Cenobite concept sketch for

Hellraiser

(courtesy Clive Barker).

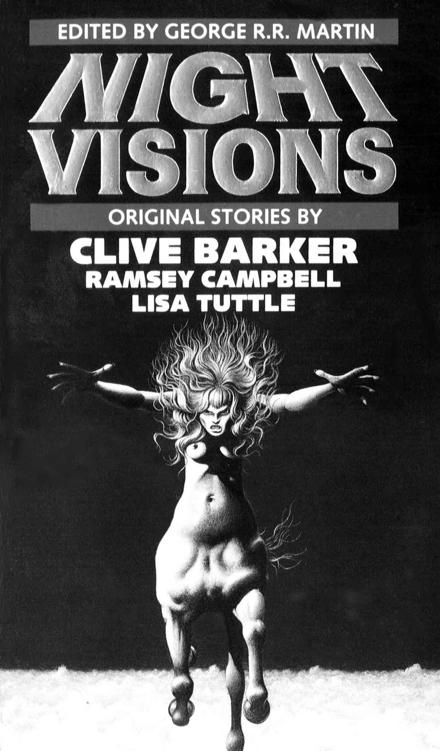

These same preoccupations would resurface when Barker wrote

The Hellbound Heart

novella almost a decade later. Originally published in 1987 as part of the

Night Visions 3

anthology—alongside stories by Ramsey Campbell and Lisa Tuttle—the tale is prefixed by a quote from John Donne’s

Love’s Deitie

(“I long to talk with some old lover’s ghost, Who died before the god of love was born.”) and differs from the finished

Hellraiser

in a number of ways.

First, we are provided with more explanation about the puzzle box itself: created by a Frenchman called Lemarchand, a “maker of singing birds.”

18

Later this would form the genesis of the fourth movie in the series. Second, the Cenobites are given a definite back history: referred to as “the order of the Gash,” hinted at in the diaries of Bolingbroke and Gilles de Rais.

19

They are more conversational and far less imposing than their cinematic counterparts. During the hospital confrontation with Kirsty, one muses, “We’d better go.... Leave them to their patchwork, eh? Such depressing places.”

20

The figure we would come to call Pinhead is here asexual, bordering on female: “Its voice, unlike that of its companion, was light and breathy —the voice of an excited girl.”

21

And the Engineer creature, in the film a fleshy, noisy mass with rows of teeth, hovers at the edge of the action and only intervenes to whisk a dying Julia off at the end and then pass the box back to Kirsty. Their lines are not quite as polished, either. Compare, “Maybe we won’t tear your soul apart” with the immortal tagline everyone knows from the film.

Night Visions

, the original anthology featuring

The Hellbound Heart

(Arrow Books).

The female protagonist, Kirsty, is the friend, not the daughter, of Rory Cotton (renamed Larry in the film), a fact which holds great significance when exploring the relationship between these two characters, as well as the family dynamics we will come to later. She is also, to quote Barker, “A total loser. You can live with someone like that for the length of a novella. You can’t for a movie.”

22

Even her body works against her as Frank is chasing her through the house at the climax: “Swallowing the breath her cry had been mounted upon had brought an unwelcome side-effect: hiccups. The first of them, so unexpected she had no time to subdue it, sounded gun-crack loud.”

23