The Hidden History of the JFK Assassination (30 page)

Read The Hidden History of the JFK Assassination Online

Authors: Lamar Waldron

After leaving the Reilly Coffee Company, Oswald held no job—officially at least—for the next three months. Unofficially witnesses—including a CIA asset—saw him working for and with Guy Banister and David Ferrie. Oswald would have earned little money, since he was still under “tight” surveillance by Naval Intelligence, in hopes that the KGB would try to contact either him or Marina, so he couldn’t appear to have significant, unexplained sums of money. In addition, keeping Oswald low on funds was a way for Banister and CIA officers like David Phillips to ensure that he had little choice but to do what they asked in hopes of a large payday down the road.

As Oswald prepared for his second attempt to get himself arrested for passing out leaflets, one building, with two addresses, became

important. Dr. Kaiser points out that some of Oswald’s pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee leaflets were stamped with the address “FPCC 544 Camp St.” Kaiser writes, “This was one of two addresses used by a corner building, the other being 532 Lafayette Street, where Guy Banister Associates had [their] offices.” Banister was of course staunchly anti-Castro, and the addresses are simply one more indication that Oswald was working for Banister in the leaflet operation.

As noted earlier, historian Richard Mahoney documented that six witnesses saw Oswald with Ferrie or Banister in the summer of 1963; two of them said that Oswald was working for Banister at that time. Declassified files and Michael Kurtz later revealed additional witnesses. One uncovered by Kurtz, Consuela Martin, provides a new explanation of why Banister’s office address appeared on the pro-Castro leaflets. Kurtz writes that Martin’s office was next to Banister’s and that “she saw Oswald in Banister’s office at least half a dozen times in the late spring and summer of 1963. . . . On every one of these occasions, Oswald and Banister were together.” Oswald sometimes asked her to do translating work for him by typing documents into Spanish. Martin believes that the 544 Camp Street address was used in hopes of luring unsuspecting pro-Castro leftists to Banister’s office, thus yielding more information for Banister’s voluminous files on leftists, all of whom he viewed as Communists.

Though no one would suggest that Oswald was as far right or anti-Communist as Banister, in the Cold War environment of the early 1960s, many liberals—most notably John and Robert Kennedy—were also anti-Communist. David Kaiser points out that far from being a “sincere” member of the far left, Oswald “only embarrassed the [Fair Play for Cuba Committee] and the Castro cause in the New Orleans area, and his behavior throughout resembled that of an agent

provocateur rather than a genuine” Communist, Marxist, or other member of the far left, no matter what Oswald claimed in his media appearances.

Aside from Oswald’s using the address for Banister’s building on some of his pamphlets, there is one other curious fact about them. Oswald handed out copies of the first printing of

The Crime against Cuba

, a pro-Castro pamphlet printed in the United States in 1961. One copy wound up as FBI evidence after the assassination. However, Oswald was in Russia in 1961, when the first printing sold out. Only the fourth printing of the pamphlet was available when Oswald returned to the United States and in the summer of 1963. Oswald would have needed help in obtaining dozens of copies of the long-sold-out first printing. It’s possible that Banister ordered one or two copies for his files in 1961, but he had no reason to order dozens of copies. The pamphlet’s author was ninety years old when researcher James DiEugenio located him, but he had saved a copy of the three-dollar “28 June 1961” purchase order he had received for forty-five copies from the “Central Intelligence Agency, Mailroom Library, Washington 25, D.C.” Those first-printing pamphlets had been ordered when David Atlee Phillips was running operations targeting the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, making Phillips a possible source of pro-Castro literature for Oswald’s PR efforts.

Though Oswald wouldn’t succeed in provoking a fight by handing out leaflets until August 9, 1963, five days BEFORE that—in a letter postmarked August 4—Oswald had written to the New York office of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. In the letter Oswald says that his “street demonstration was attacked” by “some Cuban-exile(s)” and that he was “officially cautioned by police.” Clearly, Oswald was writing about what he planned to have happen six days later. In addition, Dick Russell notes that despite Oswald’s repeated writing to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee—whose mail the FBI closely monitored—and other Communist organizations, Oswald’s name “was never included on either part of the [FBI’s] Security Index, not even after he went on to set up his highly visible Fair Play for Cuba chapter.” Oswald’s absence from the list was especially odd since he was a former defector to the Soviet Union, so Russell asks, “[H]ad the FBI received word from someone to keep a relative distance from Oswald . . . because he was considered part of another intelligence operation?” The Warren Commission was never able to satisfactorily answer that question because if Oswald had been on the Security Index, he would certainly have been subject to law-enforcement attention on the day of JFK’s motorcade in Dallas.

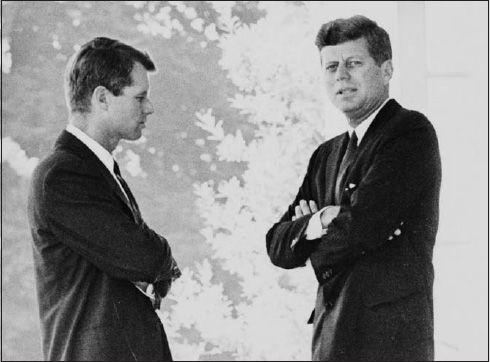

Attorney General Robert Kennedy and President John F. Kennedy waged the largest war against the Mafia that America has ever seen. They especially targeted Louisiana-Texas godfather Carlos Marcello.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

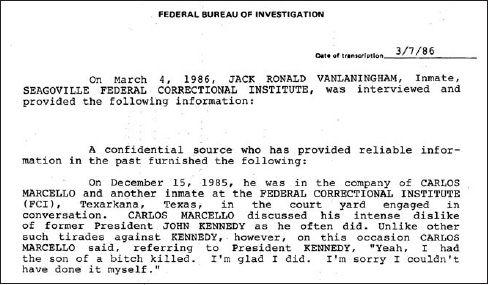

In 1985, Carlos Marcello—for decades the most powerful godfather in America—confessed to an undercover FBI informant that he ordered the assassination of President Kennedy.

BETTMAN/CORBIS

The FBI obtained Marcello’s JFK confession as part of a two-year undercover operation, code-named CAMTEX. In addition to his confession, Marcello talked on undercover FBI audio tapes about his meetings with Lee Oswald and Jack Ruby.

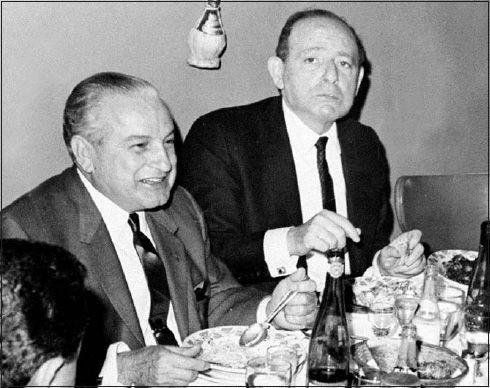

Marcello’s partner in JFK’s murder was Tampa godfather Santo Trafficante (right), seen here with Marcello (left) in 1966. In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded JFK was likely murdered by a conspiracy and “found that Trafficante, like Marcello, had the motive, means, and opportunity to assassinate President Kennedy.” Shortly before his death, Trafficante confessed his role in JFK’s assassination to his attorney.

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS ARCHIVE

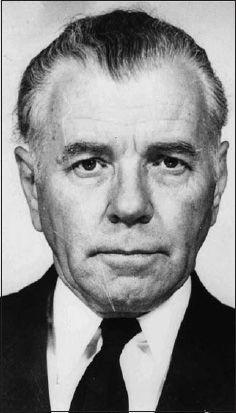

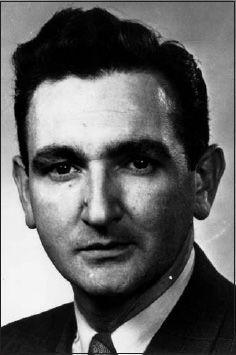

Guy Banister, the former FBI Special Agent in charge of Chicago, worked as Marcello’s private detective in 1963.

David Ferrie, a pilot, also worked for Marcello in 1963.

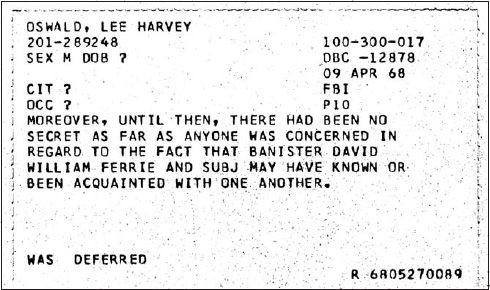

The Assistant Chief of the New Orleans CIA office said that Banister, Ferrie, and Oswald performed work for the CIA in 1963. Numerous witnesses saw Oswald with Banister and Ferrie in the summer of 1963, and this CIA card shows the Agency was aware of their connections.