The Hippopotamus Pool (10 page)

Read The Hippopotamus Pool Online

Authors: Elizabeth Peters

Tags: #Mystery & Detective - General, #Detective, #Detective and mystery stories, #Mystery & Detective, #Mystery, #Fiction - Mystery, #General, #Egypt, #Suspense, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Large Type Books, #Fiction

Whether it was prayer or the herbal incense or my medication or simply the passage of time, Miss Marmaduke reemerged into the world much improved in appearance and in manner. At dinner that evening I was surprised to see her wearing a forest-green frock that flattered her sallow complexion and displayed a figure more shapely that I had expected. For the first time since I had met her she looked as young as she claimed to be—in her early twenties, to be precise.

When I complimented her on her frock she lowered her eyes. "I hope you do not think me frivolous, Mrs. Emerson. My illness, brief and inconsequential though it was, made me realize that I had wandered from the way. The physical body and its trappings, of grief or vanity, are meaningless; I have rededicated myself to the higher path."

Good Gad, I thought. She is almost as pompous as Ramses.

Ramses it was who responded, with a long-winded lecture in the course of which he referred to the system of Hegel,

The Kabbalah

and Hindu mysticism. I have no idea how he picked up such stuff. After a while Emerson, who is quickly bored by philosophy, turned the conversation to Egyptian religion. Miss Marmaduke responded with wide-eyed interest and breathless questions. It was constantly Professor this and Professor that, and what is your opinion, Professor?

Being a man, Emerson did not at all object to these attentions. Not until the end of the evening was I able to raise the rather more important subject of lessons.

"Whenever you like, Mrs. Emerson" was the immediate response. "I have been ready all this time—"

"There is no need to apologize," I said rather brusquely. "You could not help being taken ill, and before that we were busy making the arrangements for departure. Tomorrow, then? Excellent. French, English history—you may start with the Wars of the Roses, they have already got to that point— and literature."

"Yes, Mrs. Emerson. Under the last heading, I had thought poetry—"

"Not poetry." I am not certain what prompted that response. It may have been the memory of an uncomfortable discussion with Ramses on the subject of certain verses of Mr. Keats. "Poetry," I continued, "is too sensational for young minds. I want you to concentrate on neglected masterpieces of literature composed by women, Miss Marmaduke—Jane Austen, the Bronte sisters, George Eliot and others. I have brought the books with me."

"Whatever you say, Mrs. Emerson. Er—you don't think that

Wuthering Heights,

for example, is too sensational for a young girl?"

Nefret gave me an expressive look. She had hardly spoken all evening— a sure sign, with her, that she had not taken a fancy to her new tutor.

"I would not suggest it if I did," I replied. "Tomorrow at eight then."

Emerson had begun to fidget. He felt I was making an unnecessary fuss about the children's education, since in his view the only subjects worthy of study were Egyptology and the languages necessary to pursue this profession. Now he stopped tapping his foot and looked approvingly at me.

"Eight o'clock, eh? Yes, quite right. You should retire early, Miss Marmaduke, this is your first day out of bed. Ramses, Nefret, it is late."

So encouraged, the others retired, leaving us, as Emerson had intended, alone.

"Miss Marmaduke is certainly a changed woman, Emerson."

"She looks much the same to me," said Emerson vaguely. "Have you spoken to her about trousers, Peabody?"

"I was not referring to her attire, Emerson, but to her demeanor."

"Oh. It seems much the same to me. Come along, Peabody, early to bed, eh?"

Later, when Emerson's deep breathing assured me he was deep in the arms of Morpheus and the moonlight lay in a silver path across our couch, and the soft sighing of the night breeze and the ripple of water should have induced repose in me—later, I lay sleepless, pondering the transformation of Miss Marmaduke, or Gertrude, as she had asked me to call her.

There was one obvious explanation for the improvement in her appearance and manners. Emerson's magnificent physical attributes and gentle manners (toward females) frequently prompted women to fall in love with him (hopelessly in love, I hardly need say). This would not have been the first time it had happened.

In fact, now that I came to think about it, it happened almost every year! The young lady journalist, the tragic Egyptian beauty who had given her life for his, the mad High Priestess, the German baroness—and, most recently, the mysterious woman called Bertha, whom Emerson had described as being as deadly and sly as a snake. He denied she had been in love with him, but then he always denied it (either through inherent modesty or fear of recriminations).

Really, it was getting monotonous. I hoped Miss Marmaduke was not going to be another of Emerson's victims. It was possible that she was something more sinister. Had it been an example of my well-known prescience that made me see her as a great black bird? Not a crow or a rook, however—a larger, more ominous bird of prey.

The vultures were gathering.

When a conqueror passes on, lesser men divide the broken fragments of his conquests. Witness, for example, the events following the death of Alexander the Great, when his generals carved the leaderless empire into kingdoms for themselves. It might seem extravagant to compare Alexander with Sethos, our great and evil opponent, yet they had had much in common: ruthlessness, intelligence, and, above all, the indefinable but potent quality called charisma. Like Alexander's empire, Sethos's monopoly over the illegal antiquities trade in Egypt had rested on his abilities alone. Like Alexander's, his empire was now leaderless—and the carrion birds were hovering.

Riccetti must be one of them. His retirement a decade or more ago might not have been voluntary. No, not voluntary, I thought; he had been forced out of the business by Sethos, who was now removed from the scene. Was "Miss Marmaduke" a hireling of Riccetti's, or a competitor? How many others were after our tomb? And which of them "would help us if they could"? That statement of Riccetti's was meant to imply that he was one of the second group, but of course it could not be taken at face value. Honesty is not a conspicuous characteristic of criminals.

The death of Sethos had not freed us from peril. On the contrary,' it had multiplied the number of our enemies. Emerson's (and my) unending war against the illegal antiquities trade had focused on us the enmity of the dealers in that trade, and if the tomb for which we searched was indeed unknown and unlooted, every thief in Egypt would try, by any means possible, to get to it before we did.

Naturally I had no intention of discussing this interesting development with Emerson. He had certainly arrived at the same conclusion; but, being Emerson, he had chosen to ignore the dangers and would continue to do so until someone dropped a rock on him. As usual it was up to me to take the precautions Emerson refused to take—to guard him and the children, to be constantly on the alert for peril, to suspect everyone. No matter. I was up to the job. I rested my head against the shoulder of my oblivious husband and succumbed to sweet, dreamless slumber.

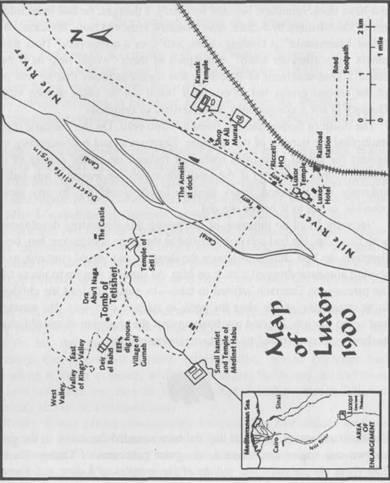

On the afternoon of the tenth day the boat rounded the curve in the river and we saw spread out before us the great panorama of Thebes. On the East Bank the columns and pylons of the temples of Luxor and Karnak glowed in the rays of the setting sun. On the west a rampart of cliffs enclosed the bright green fields and the desert that bordered them.

The West Bank was our destination, and as the dahabeeyah maneuvered in toward the shore, we were all at the rail. Miss Marmaduke had been unable to fit into my trousers, though I had offered a pair. (She was a good deal larger in that region than she had appeared.) Complying—as she explained at unnecessary length—with my wishes, she wore a walking skirt short enough to display neatly booted feet, and a shirtwaist and pith helmet. A wide leather belt defined her waist. She looked quite presentable, but no masculine eye would linger on her when Nefret was present. I had caused to be made for the girl costumes similar to my own: trousers and matching coats of flannelette or serge, covered all over with useful pockets. Stout little boots, a shirt and neatly knotted tie, and the usual pith helmet completed the ensemble. Her hair was clubbed at the nape of her neck, but she did not look at all like a pretty boy.

The first person we saw was Abdullah. He and his crew had come down by train the previous week, and I did not doubt he had set men to watch for us so that he could be on hand when we docked. He and the others were staying in Gurneh. Abdullah had innumerable friends and relations in the village, and it was conveniently close to the area in which we would be working.

After he and his entourage had come on board we went to the saloon for conversation and refreshments—whiskey and soda for us, gossip for the others, since the laws of Ramadan were still in effect. Abdullah, stately as a biblical patriarch, seated himself in a carved armchair. The others— Daoud, Abdullah's nephew, his sons Ali and Hassan and Selim—settled down comfortably on the floor, and Ramses settled down next to Selim, who had been his close companion (i.e., partner in crime) one memorable season. Though only a few years older than Ramses, Selim was now a married man and the father of a growing family. He had kept his boyish joie de vivre, however, and he and Ramses were soon deep in conversation.

"All is well, Emerson," said Abdullah. "We have procured the supplies you requested and have made it known that you will be hiring workers. Shall I tell them to come tomorrow?"

"I think not," Emerson replied. He took out his pipe. By the time he had finished fussing with the cursed thing and got it lit, Abdullah, who knew Emerson well, was watching him intently. Such deliberation on the part of a man who was notorious for his impatience presaged an important announcement.

"We are all friends here," Emerson began. "I trust you as my brothers and I know that my words will remain shut in your hearts until I give you leave to share them."

He spoke English for the sake of Nefret and Gertrude, but the formal, sonorous speech patterns were those of classical Arabic. They had the effect he intended; solemn nods and exclamations of "Mahshallah," and "Ya salam!" followed.

"There is a lost tomb in the hills of Drah Abui Naga," Emerson went on. "The tomb of a great queen. I have had a quest laid upon me by those whose names must not be named; I have taken a mighty oath to find that tomb and save it. My brothers, you know there are those who would prevent me if they knew my intent; there are those who would ... oh, curse it."

His pipe had gone out. Just in time, too; he had become carried away by his own eloquence and was in danger of overdoing the melodrama. I caught the eye of Abdullah, whose face was preternaturally grave but whose twinkling orbs gave him away, and I said, "The Father of Curses speaks well, my friends, don't you agree? I am sure that you, who are his brothers, will swear an equally mighty oath to aid and protect him."

The others were not as critical as Abdullah; emphatic assurances, in Arabic and English, followed, and tears of emotion sparkled in Selim's long lashes. Emerson looked at me reproachfully, for he does enjoy making speeches, but since I had summed up the general situation so neatly, there was nothing more for him to add.

"So," said Abdullah. "When will you begin hiring?"

"Not for another day or two. I will let you know."

Shortly thereafter our men took their departure. Ramses and Nefret accompanied them as far as the gangplank, and I sorted through the mail Abdullah had delivered.

"I am afraid there is nothing for you, Miss Marmaduke," I remarked.

She took the hint. Rising, she said, "The messages I await will not come by post. You will excuse me?"

"She has been reading too much poetry," I said, after she had gone. "I had hoped to find something from Evelyn, but there is only this letter from Walter. It is directed to you, Emerson."

The envelope contained a single sheet of paper, which Emerson handed over to me as soon as he had scanned it. "Not very informative," he said. "He is well, she is well, the children are well."